D

A

C

O

W

I

T

S

Secretary of Defense

Federal Advisory Committee

1951 to present: A 70 year review

A Historical Review of the Infl uence

of the Defense Advisory Committee

on Women in the Services (DACOWITS)

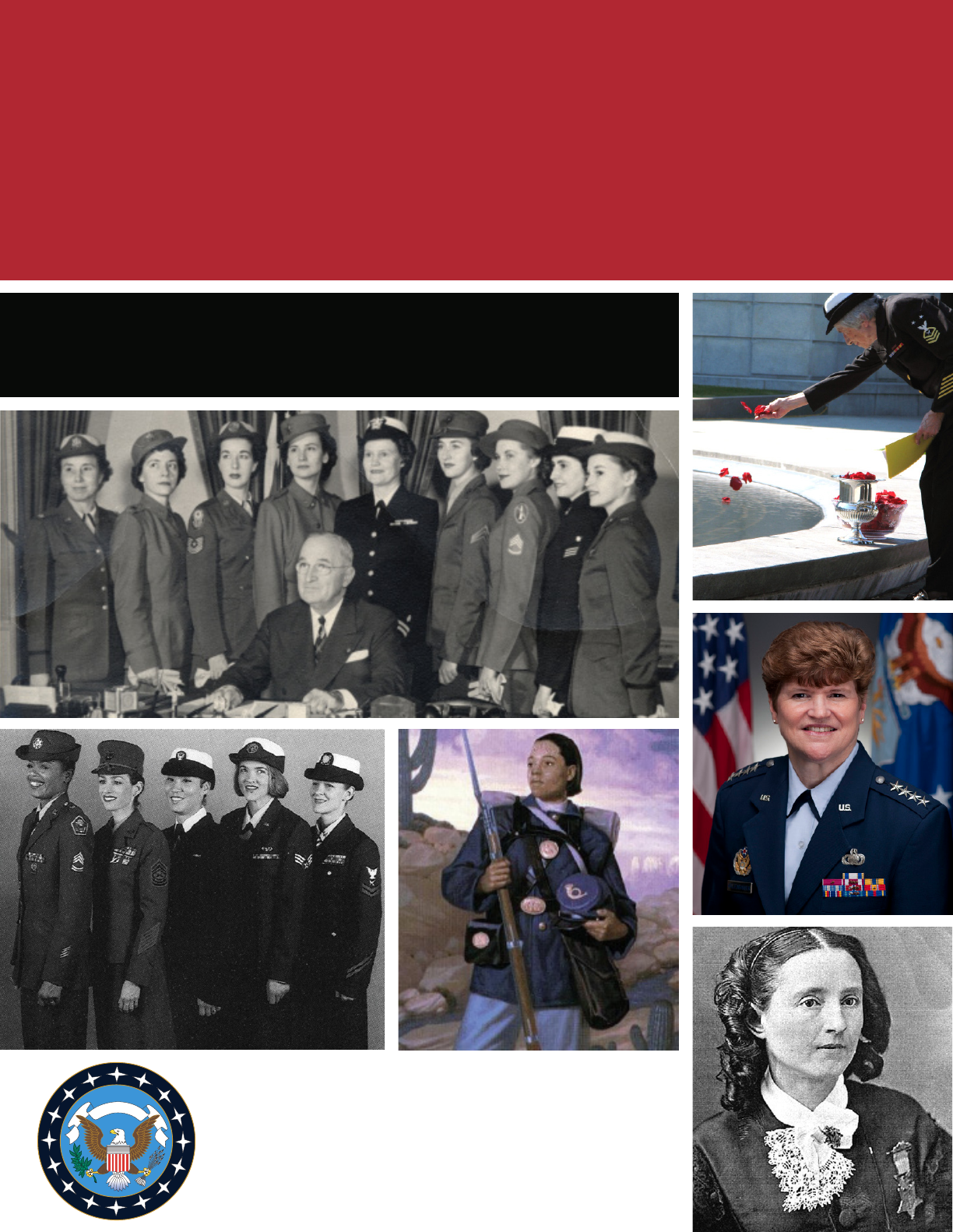

Cover photos

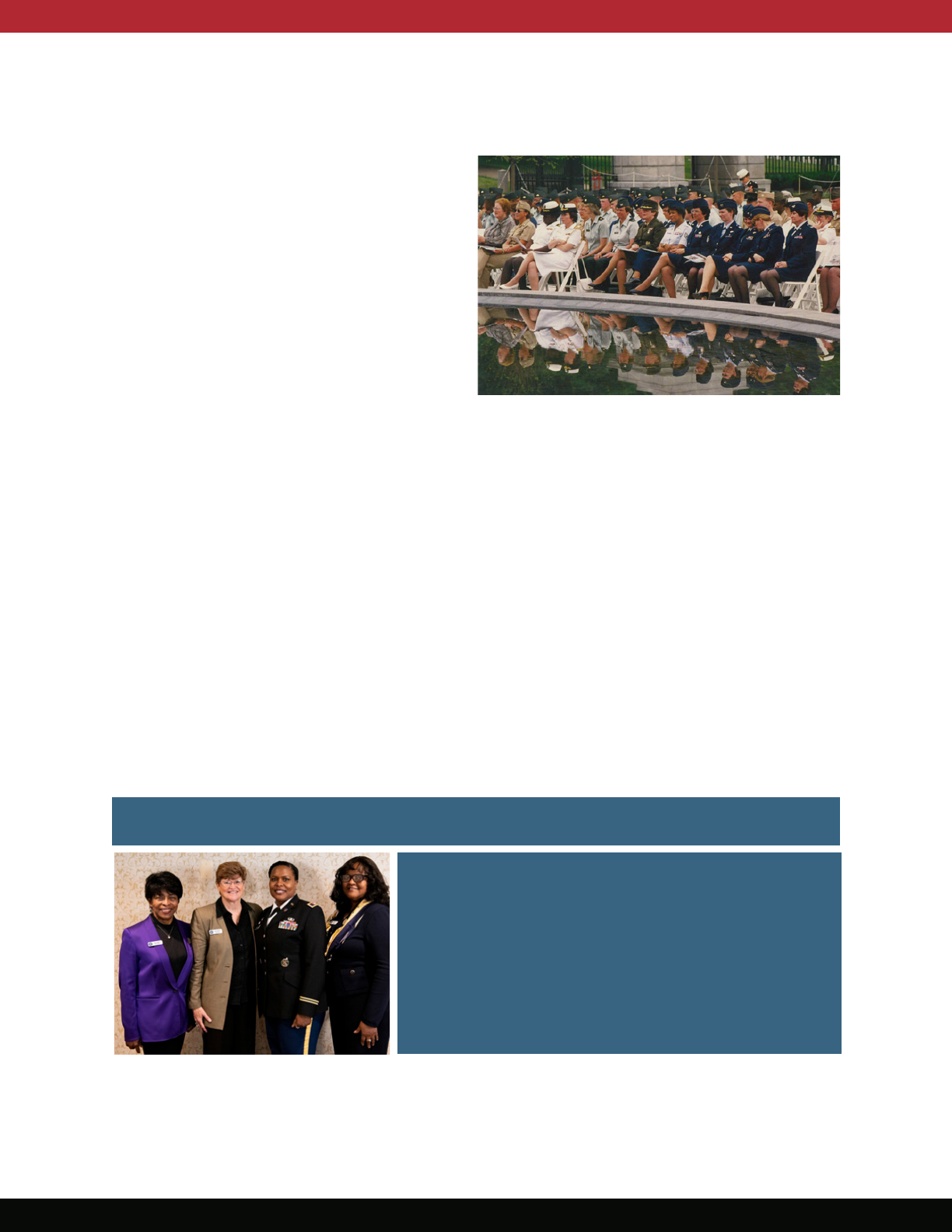

Top right

Retired Navy Master Chief Petty Ocer Anna Der-Vartanian places rose petals into the

reecting pool at the Women in Military Service for America Memorial’s annual Memorial

Day observance at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, May 26, 2008. In

1959, Der-Vartanian became the Navy’s rst female master chief petty ocer, the Navy’s

highest enlisted grade, and the rst woman in the Armed Forces to be promoted to the rank

of E-9, the highest enlisted rank in the Military Services.

Middle right

General Janet Wolfenbarger, the Air Force’s rst female four-star general, is the highest

ranking military woman ever to serve on DACOWITS and the longest serving consecutive

DACOWITS Chair.

Bottom right

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was a prisoner of war and surgeon during the Civil War. She is the

only woman ever to be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Top left

President Truman signing the 1948 Women's Armed Services Integration Act, which

authorized women to serve as permanent, regular members of the U.S. military.

Bottom left

This photo was used to create the 1997 Women in Military Service stamps in response to

DACOWITS’ 1974 recommendation.

Center

Private Cathay Williams, a former slave, was the only woman to serve in the U.S. Army as a

Bualo Soldier during the Civil War, posing as a man under the pseudonym William Cathay.

A Historical Review of the Inuence

of the Defense Advisory Committee

on Women in the Services (DACOWITS)

From 1951 to Present: A 70-Year Review

December 2020

Authors

Rachel Gaddes

Sidra Montgomery

Zoe Jacobson

Shannon Grin

Jordan Stangle

Ayanna Williams

Jessica Myers

Rob Bowling II

Submitted to

Defense Advisory Committee on Women

in the Services (DACOWITS)

4800 Mark Center Drive, Suite 04J25-01

Alexandria, VA 22350-9000

Project Officer

COL Elaine Freeman

Submitted by

Insight Policy Research, Inc.

1901 North Moore Street

Suite 1100

Arlington, VA 22209

Project Director

Rachel Gaddes

Contents

Chapter 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................................................................... 1

Chapter 2. History of Women in the U.S. Military .............................................................................................................2

Women’s Devotion to Military Service Began Before They Were Granted Ocial

Permission to Serve ........................................................................................................................................................................2

Expansion of Women’s Service in Nursing and Administrative Roles ...............................................3

World War II and Increased Opportunities for Women in the U.S. Military .....................................4

The All-Volunteer Force and Women’s Admittance to Military Service Academies..............5

Expansion of Combat Roles for Women.......................................................................................................................6

Women in the Military Today ...................................................................................................................................................7

Chapter 3. History of DACOWITS, 1951 to Present ..........................................................................................................8

Committee Size and Membership ................................................................. ..................................................................... 9

Committee Organizational Structure ............................................................................................................................ 10

Areas of Focus Over the Years ................................................................ .............................................................................. 11

Installation Visits .............................................................................................................................................................................. 12

Guidance for Committee Members ................................................................................................................................. 14

DACOWITS Support of Other DoD Activities ......................................................................................................... 15

Looking Ahead: The Future of DACOWITS .............................................................................................................16

Chapter 4. Analysis of DACOWITS Recommendations, 1951 to Present .................................................. 17

Trends in DACOWITS Recommendations ............................................................................................................... 17

Recommendation Analysis Methods ............................................................................................................................ 17

Common Themes Addressed in Recommendations ......................................................................................18

Common Types of Recommendations ......................................................................................................................20

Common Purposes of Recommendations .............................................................................................................20

Common Target Entities for Recommendations ................................................................................................ 21

DACOWITS Recommendations Across the Decades .................................................................................. 22

History of DACOWITS Areas of Concern as Reected in Its Recommendations ................ 22

Career Progression ...................................................................................................................................................................... 29

Family Support ................................................................................................................................................................................. 34

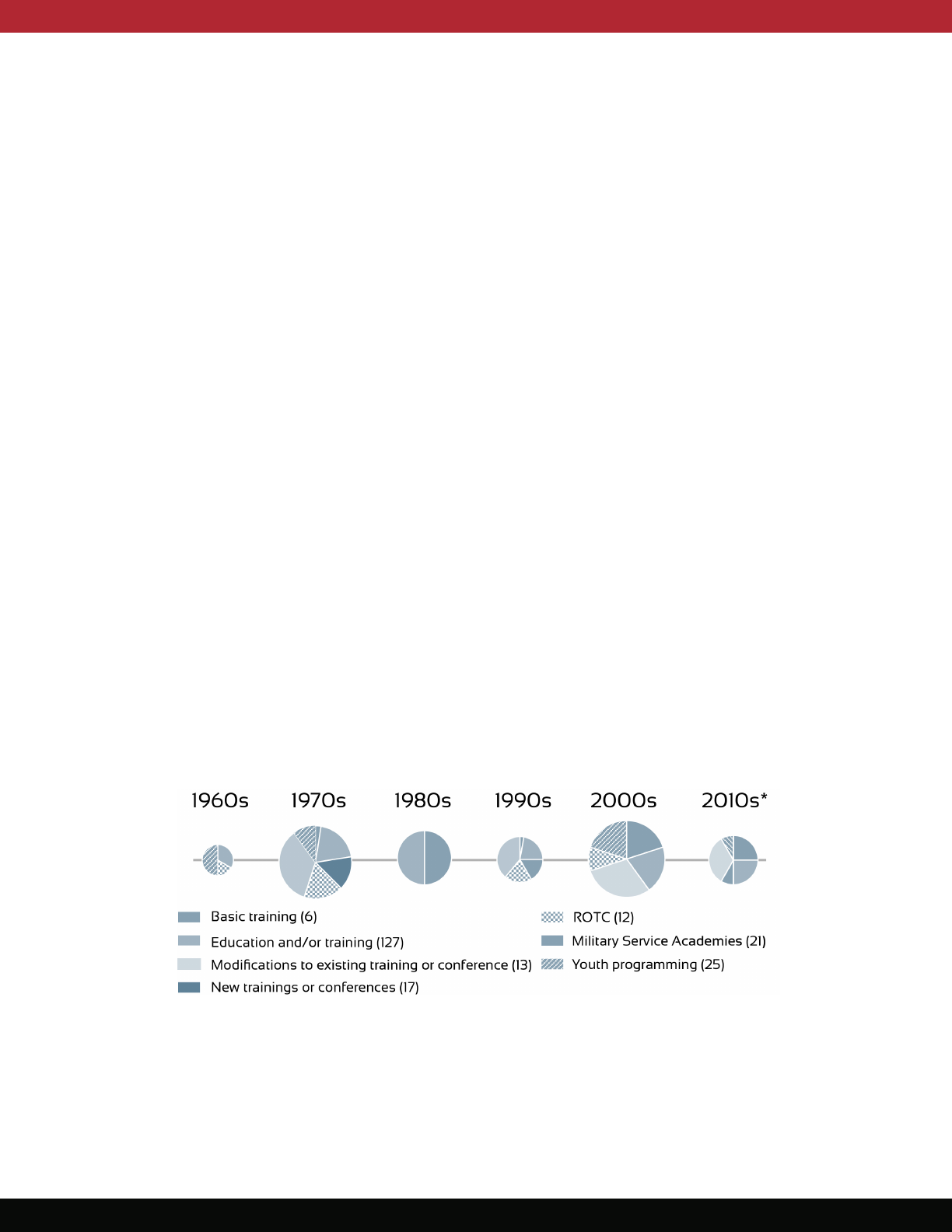

Education and/or Training ..................................................................................................................................................... 36

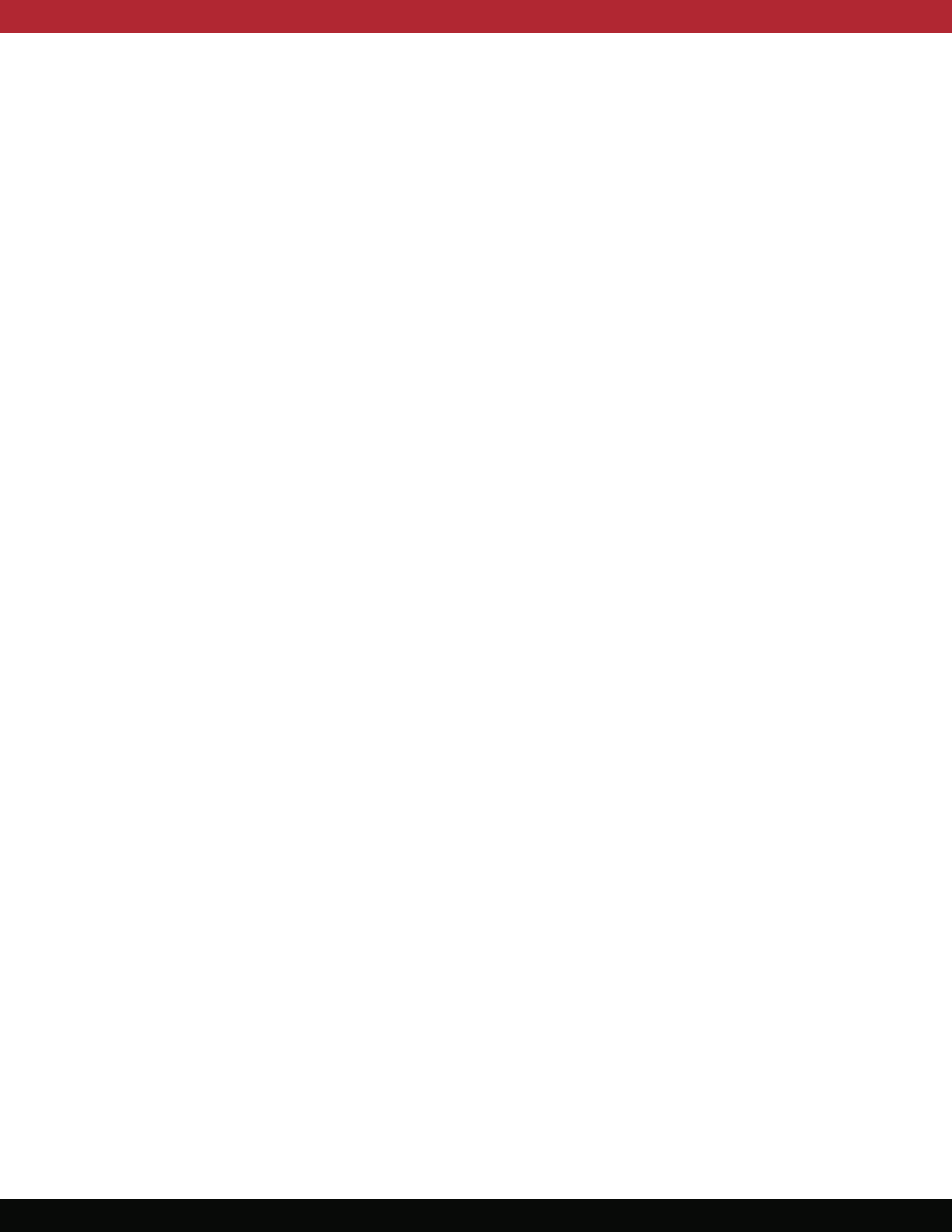

Women’s Health and Well-Being ..................................................................................................................................... 39

Pregnancy ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 39

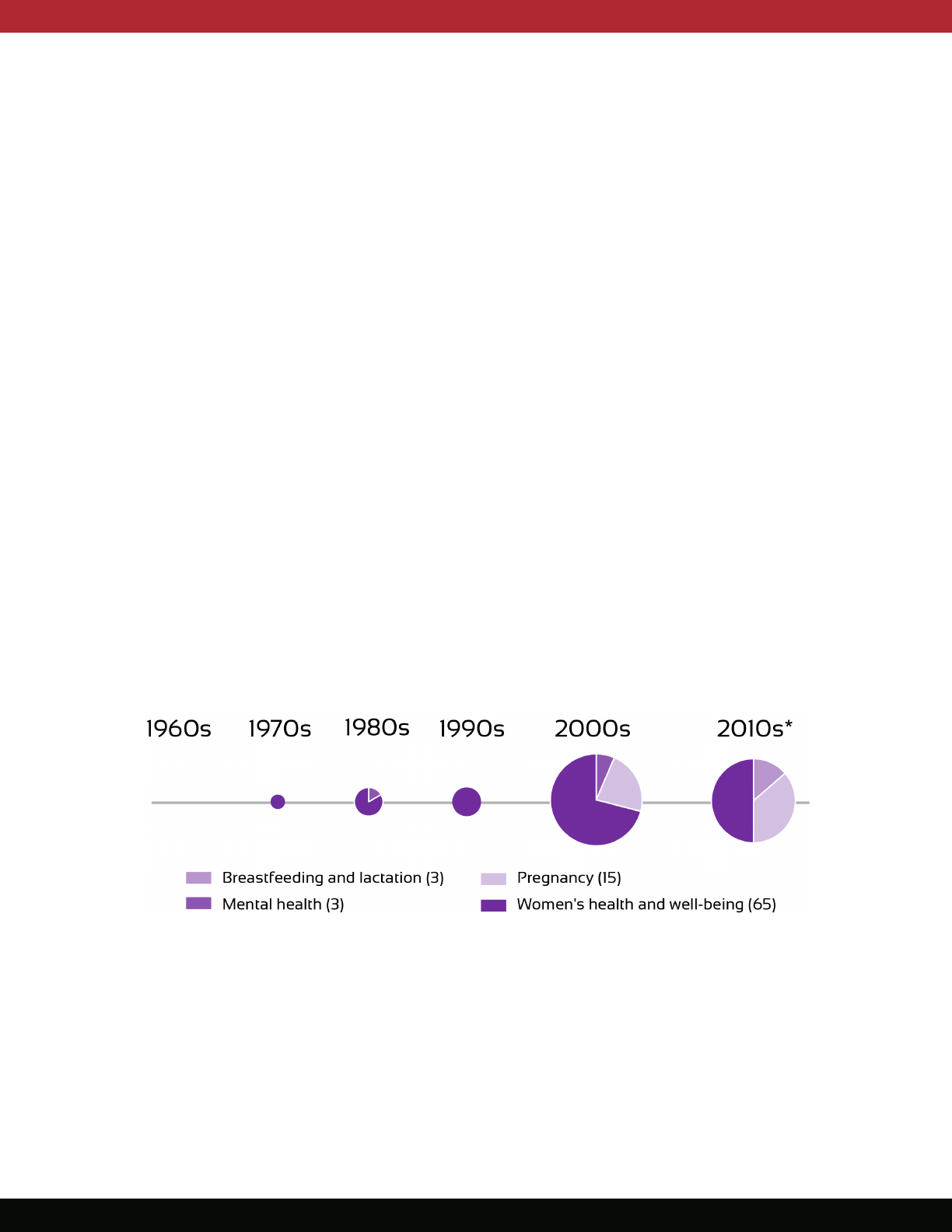

Marketing and Recruitment ..................................................................................................................................................40

Additional Recommendations ........................................................................................................................................... 42

Chapter 5. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................................................... 46

References ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 48

As the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services (DACOWITS) prepares to cel-

ebrate seven decades of service to the Department of Defense (DoD) next year, we are proud to

present this retrospective on the inuence of this important Committee during the past 70 years.

As the 50th and longest tenured Chair of DACOWITS, it is my honor to introduce this study. I

served in the U.S. Air Force for 35 years, culminating my career in 2015 as the rst female four-

star general in my branch of Service. I was the beneciary throughout my career of the changes

driven by DACOWITS, starting with my appointment into the rst class of women to attend the

U.S. Air Force Academy in 1976, a change advocated by DACOWITS.

e work of this Committee has proven to be of utmost value to DoD. As one of the few Feder-

al Advisory Committees that conducts annual installation visits to meet with Service members

across all branches, we serve as the eyes and ears of the Department to ferret out issues and

propose recommendations to address them. e Committee has proered more than 1,000 rec-

ommendations during the past 70 years, 98 percent of which have been either fully or partially

implemented by DoD.

Ms. Helen Hayes, the famous actress, and—more pertinent to this retrospective—a member of the

inaugural Committee, said in 1951: “All of us must work at patriotism, not just believe in it. For

only by our young women oering their service to our country as working patriots in the Armed

Forces ... can our defense be adequate.” is quote is on the DACOWITS coin that is presented to

individuals during our installation visits as a token of appreciation for outstanding support. Ms.

Hayes’ sentiment from 1951 remains apropos today, almost seven decades later.

Aer serving in uniform for more than three decades, followed shortly thereaer by chairing DA-

COWITS for the past 4 years, my sincerest hope is that there will be a time when DACOWITS is

no longer needed. As heartfelt as that hope is, I am absolutely convinced the need for DACOWITS

remains as valid today as when this Committee was rst formed. I am extraordinarily proud to

be a part of the important work of DACOWITS. We conduct one of our public quarterly business

meetings every March during Women’s History Month. Annually at that meeting we pause to re-

ect on the substantial progress made since DACOWITS was established in 1951. en we turn to

the Committee’s current study topics with the profound realization our work is not yet done.

Janet C. Wolfenbarger

General (Retired), U.S. Air Force

DACOWITS Chair

1

Chapter 1. Introduction

I

n preparation for the DACOWITS’

upcoming 70th anniversary in

2021, the Committee conducted

an analysis of its eorts and impact

during its history. As an anniversary

synopsis, this chapter does not

reect every issue DACOWITS has

studied during its tenure. DACOWITS’

recent work in 2019 and 2020

is reected here on important

topics such as domestic abuse,

conscious and unconscious gender

bias, and marketing strategies, but

implementation of recommendations

by the Department of Defense and

Military Services remains ongoing. The

purpose of this chapter is to present

an overview of DACOWITS’ impact

through a detailed review of the

more than 1,000 recommendations

made by the Committee. These

recommendations have addressed

dozens of issues and challenges

facing women in the U.S. military,

some of which have been resolved over time and others that persist today. To provide

context for this analysis, the chapter also includes a brief overview of women’s service and

a review of the history of the Committee.

Chapter 2 presents a history of women’s service in the U.S. military. Chapter 3 provides

an overview of the history of DACOWITS from 1951 to present day. Chapter 4 describes

the research team’s methodology for analysis, and presents the results of the analysis of

DACOWITS’ recommendations over time. Chapter 5 presents the conclusion.

Women in the U.S Navy. Photo from the DACOWITS archives

2

Chapter 2. History of Women in the

U.S. Military

W

omen’s service has been integral to the success of the Military Services of the

United States. Hundreds of years before women were allowed to serve, they aided

the ght by ensuring troops were fed and clothed, and some joined the ranks

disguised as men. The U.S. military’s reliance on women as nurses and the wartime need for

additional support opened the door for women’s permanent place in the Military Services.

Despite restrictions on their service and occupational roles over the years, women have

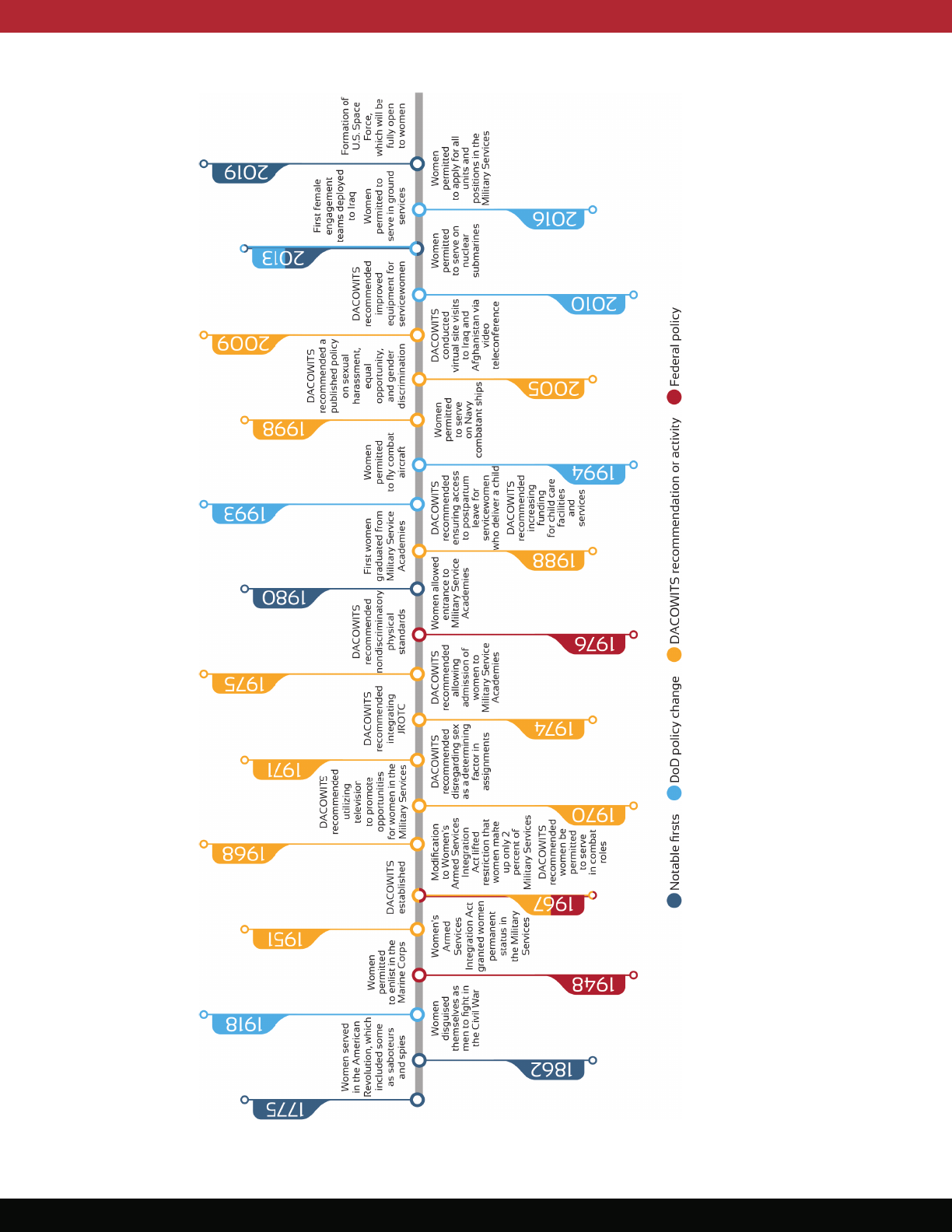

continued to succeed and break barriers in the U.S. military. Table 2.1 presents a summary of

the number of women who have served and died in service from the Civil War through the

conicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

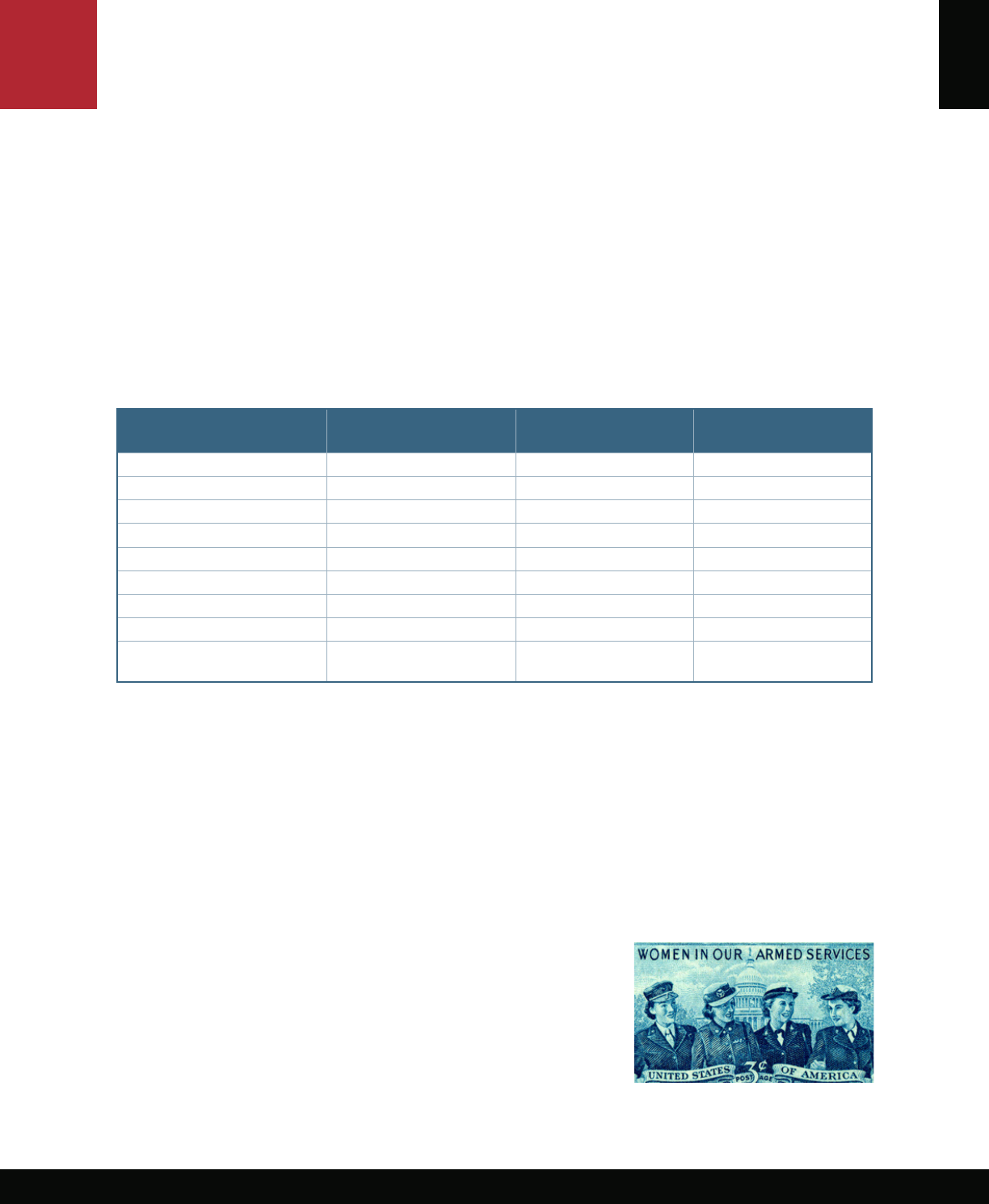

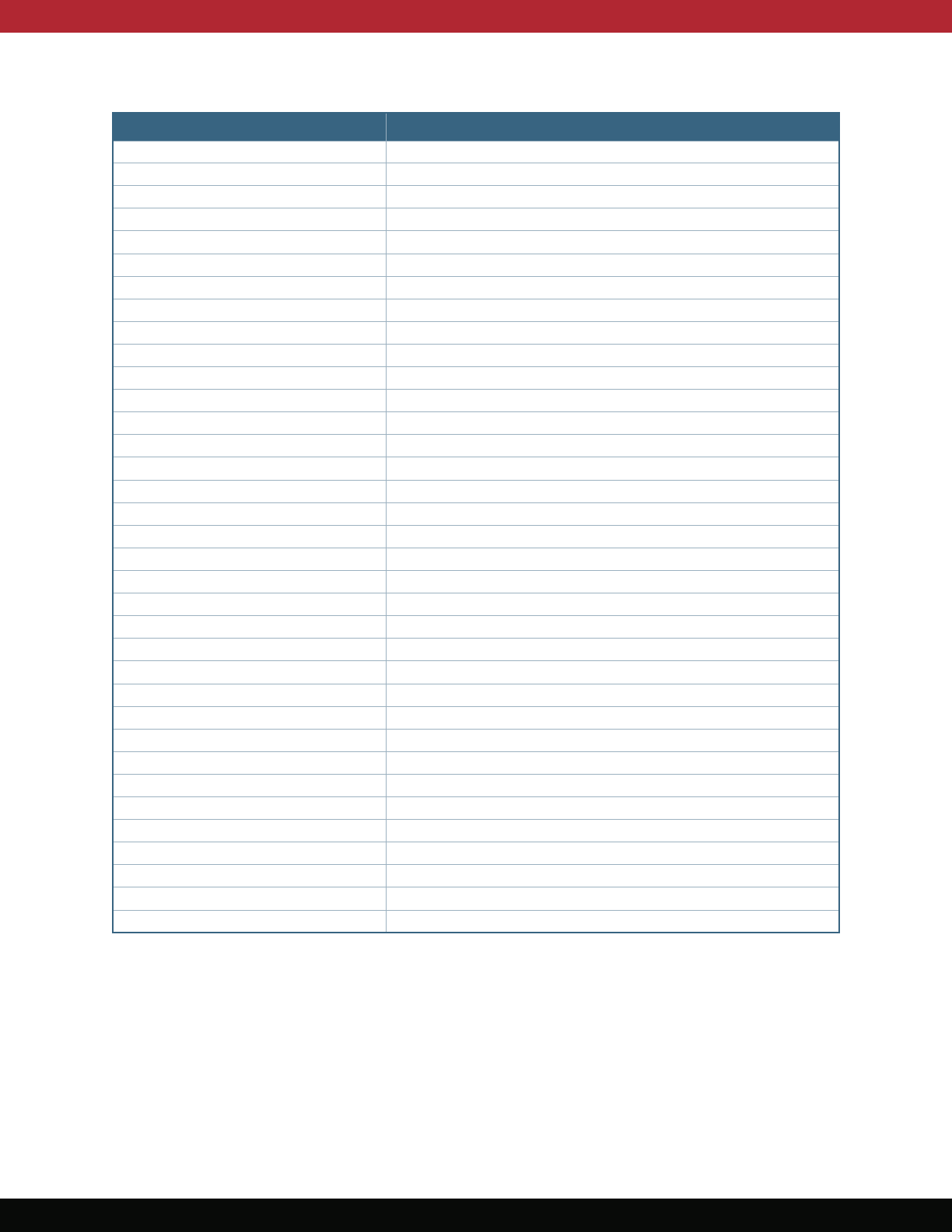

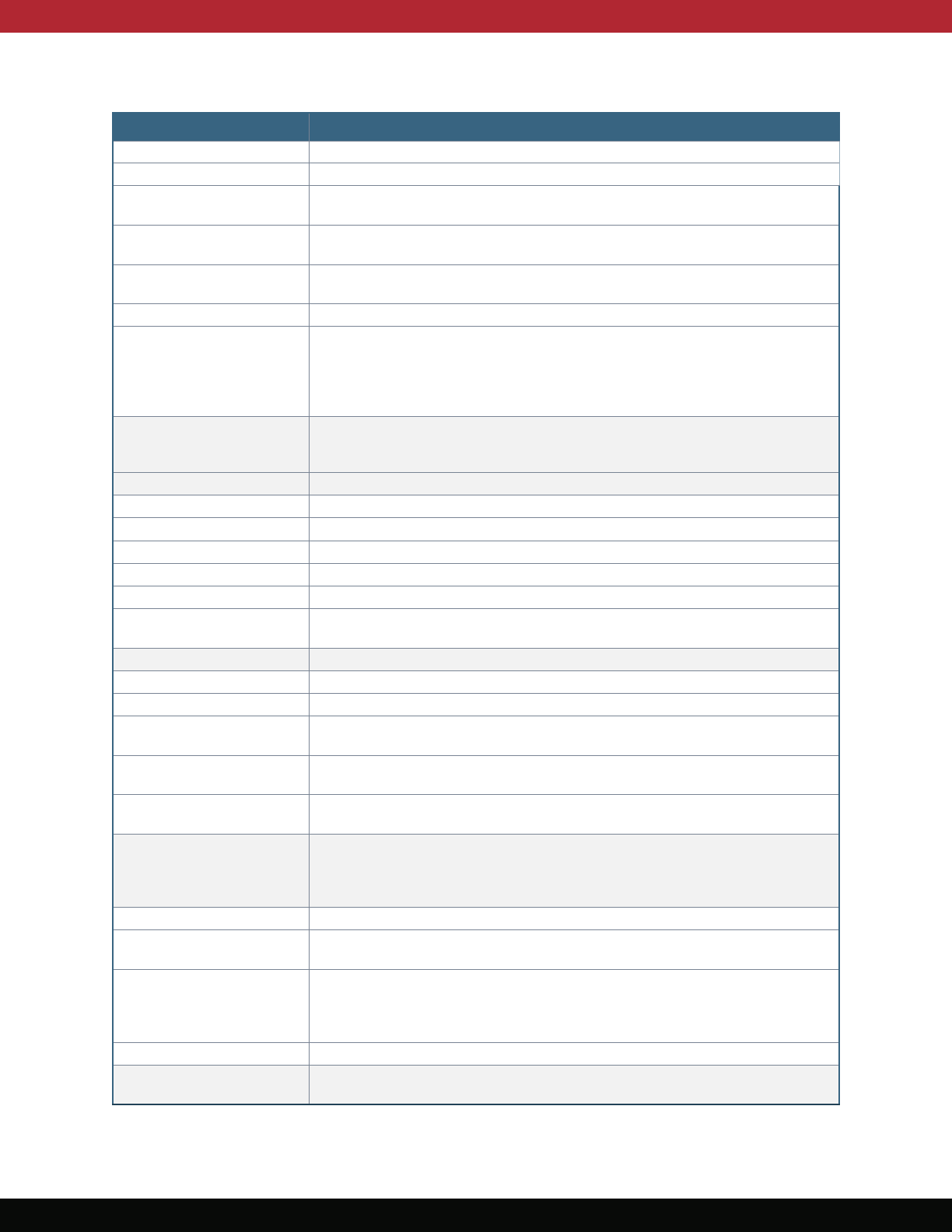

Table 2.1. Number of Women Who Served and Died in Service by Conflict

War/Conict Period Dates

Number of Women

Who Served

Female Casualties

Revolutionary War 1775–1783 Unknown

a

Unknown

a

Civil War 1861–1865 6,000

b, c

Unknown

c

Spanish-American War 1898–1902 1,500

a

22

a

World War I April 1917–November 1918 35,000

c

400

c

World War II September 1940–July 1947 400,000

a

400

a

Korean War June 1950–January 1955 50,000

a

2

a

Vietnam War August 1964–May 1975 265,000

d

8

a

Persian Gulf War 1990–1991 41,000

e

15

a

Operation Enduring Freedom

and Operation Iraqi Freedom

2001–2014 700,000

a

161

a

Notes:

The number of women who served in each conict and the casualty count were difcult to determine, especially prior to

World War I. The number of women who served consists of those who served at home and abroad during the conict time

period. The information presented here reects conicts with different lengths, scopes, and personnel levels.

a

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2017

1

b

This is an estimation of the number of nurses who served in the Civil War. Historians have also estimated approximately

400 women served in disguise as men.

c

U.S. Army, n.d.

2

d

Of this number, 7,500 women were deployed abroad.

e

Bellafaire, 2019

3

Women’s Devotion to Military Service Began Before They Were

Granted Official Permission to Serve

During the American Revolution (1775 to 1783), women

provided support to the battleeld by serving as nurses,

cooks, laundresses, seamstresses, and water bearers. These

women, known as “camp followers,” took care of essential

domestic responsibilities for American troops who were

at war. Some women served as saboteurs and spies who

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

3

aided American troops by garnering important information, relaying messages, or carrying

contraband.

4, 5, 6

Although women had no ocial role in the U.S. military, their service was

vital to the sustainment and success of American troops. Decades later in the 1830s, the

Lighthouse Service, which would later become the Coast Guard, assigned women as

lighthouse keepers for the rst time.

7

During the Civil War (1861 to 1865), most women who served were nurses who provided

medical care to both Union and Confederate troops; it is estimated 6,000 women provided

nursing support.

8

In 1862, women served on Red Rover, the Navy’s rst hospital ship,

providing medical care to Union soldiers.

9

Women also served as cooks, laundresses, and

clerks. Several hundred women disguised themselves as men to serve on the battleeld.

These women went to great lengths to join the ght and conceal their identity by cutting

their hair; adopting new, masculine names; binding their breasts; and padding their trouser

waists.

10

The Civil War produced the rst and only woman to receive the Medal of Honor. Dr.

Mary Walker served as a surgeon, providing life-saving medical care to troops. Her Medal of

Honor, rst awarded in 1865

i

,

1

described how she “devoted herself with much patriotic zeal

to the sick and wounded soldiers, both in the eld and hospitals, to the detriment of her

own health.”

11

Near the end of the 19th century, approximately 1,500 civilian women were

contracted as nurses to serve in domestic Army hospitals during the Spanish-American

War.

12

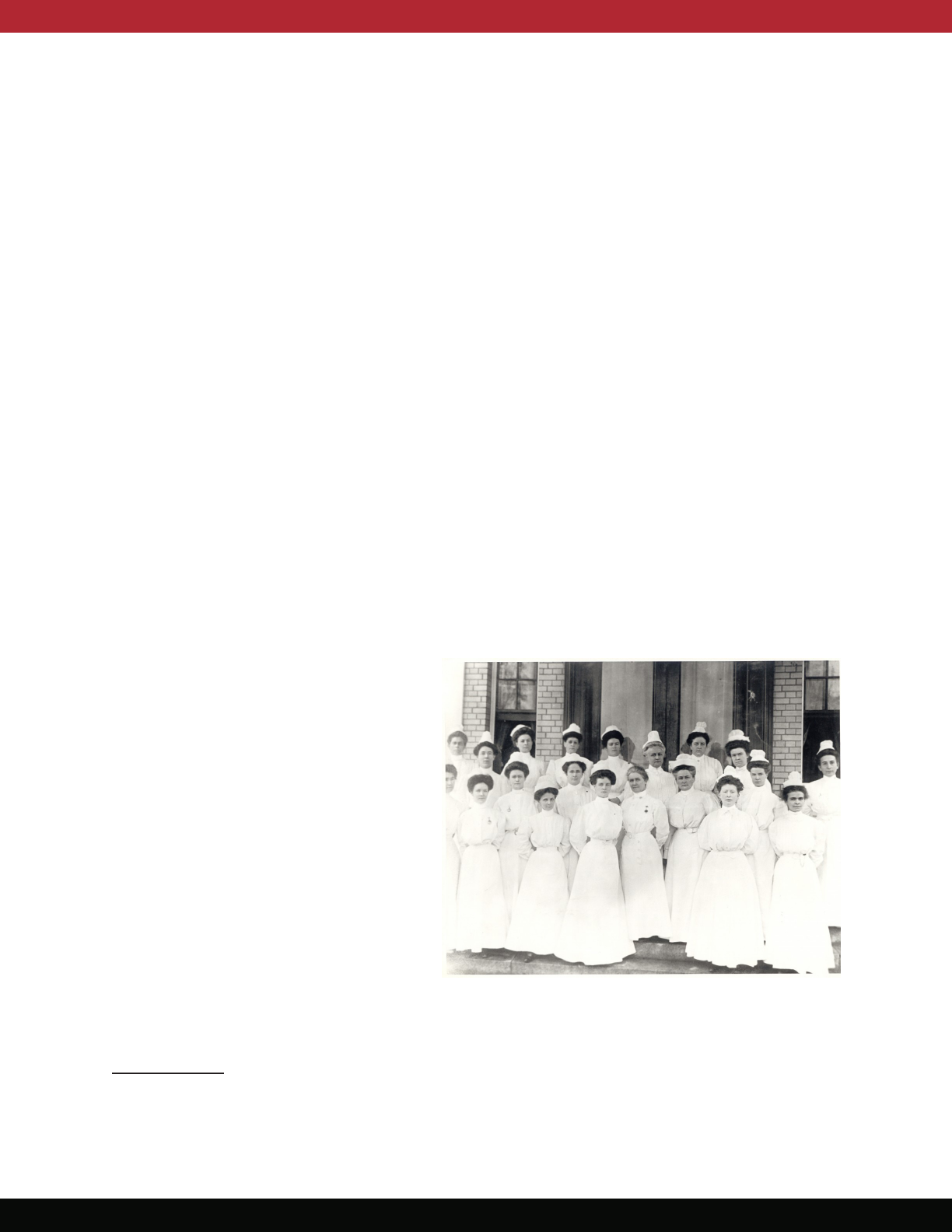

Expansion of Women’s Service in Nursing and Administrative

Roles

Women’s continued success serving as

nurses, in particular during the Spanish-

American War, led to the establishment

of the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and

the Navy Nurse Corps in 1908. The rst

20 nurses in the Navy, known as the

“Sacred Twenty,” were credited with

breaking barriers for women in that

Military Service.

13, 14

The scope and size of

women’s roles in the U.S. military greatly

expanded during World War I. More

than 35,000 women served during this

time, and nearly 400 women were killed

in action. While most female Service

members served as nurses, they also

worked as administrators, secretaries, telephone operators, and architects.

15

In 1917, the Navy

opened enlistment for women as yeomen to provide clerical support and ll other shore-

i

Dr. Walker was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Andrew Johnson in November 1865. However, her medal was

rescinded in 1917, along with several hundred others, because she was a civilian who did not have commissioned service.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter restored her medal posthumously.

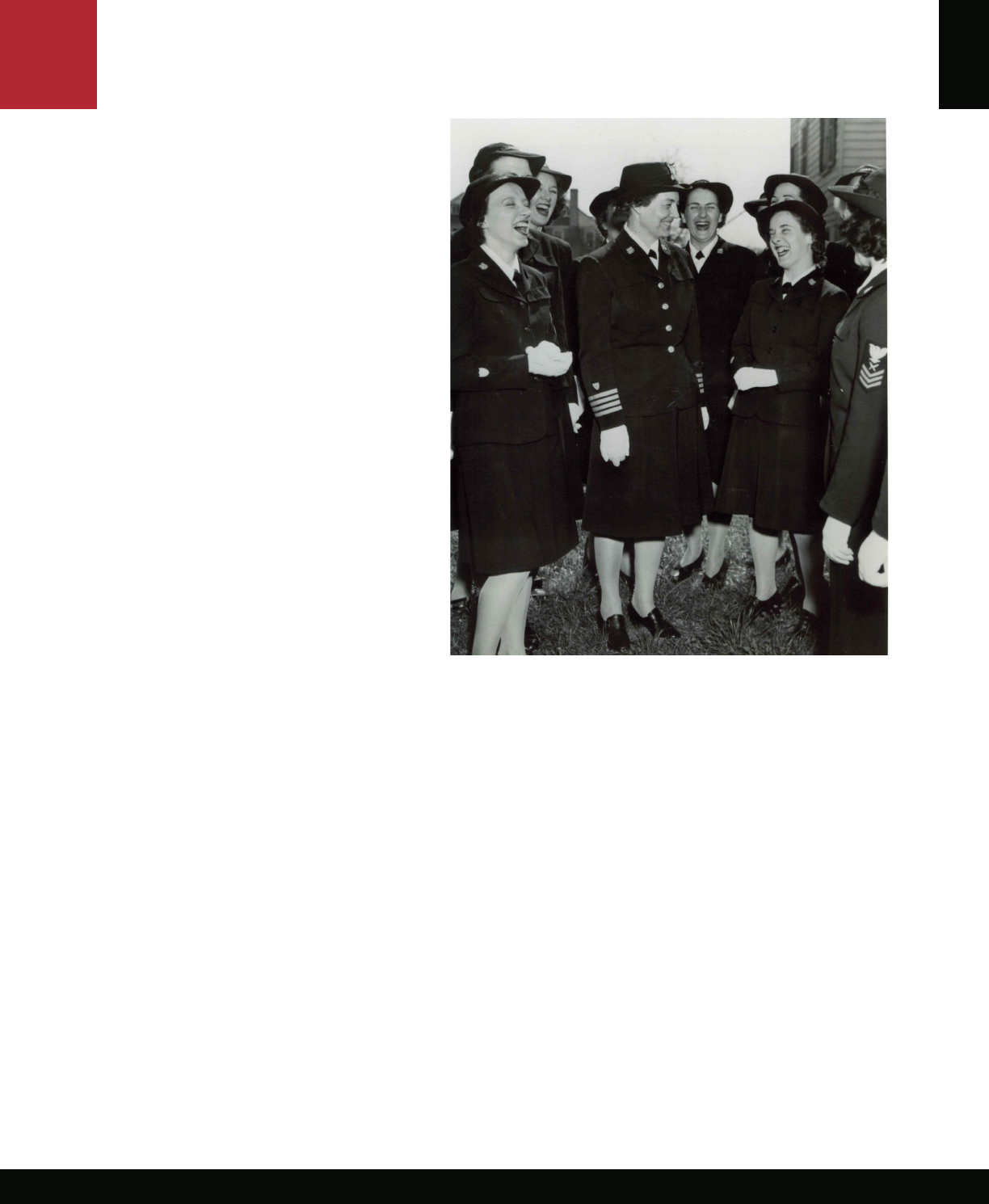

The “Sacred Twenty”: The Navy’s rst nurses, October 1908

4

related shortages. The rst enlisted woman was 21-year-old Loretta Perfectus Walsh, who

was sworn in March 21, 1917. She worked as a Navy recruiter, sold bonds, and helped nurse

sick inuenza patients during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

16

Female yeomen worked in

Washington, D.C., primarily performing clerical and other oce work but sometimes serving

as mechanics, truck drivers, camouage designers, cryptographers, telephone operators,

and translators.

17

In 1918, the then-Secretary of the Navy allowed women to enlist in the

Marine Corps for the rst time. Opha May Johnson, the rst woman to join the Marine Corps,

enlisted August 13, 1918.

18

World War II and Increased Opportunities for Women in the

U.S. Military

World War II saw yet another expansion of women’s roles, both in the Military Services and

industrial workplaces on the home front. The need for women’s service was reected in

the broadening of ocial military roles for women beyond nursing and clerical work, which

included the establishment of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (later the Women’s Army

Corps), the Women Airforce Service Pilots, the Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer

Emergency Service, the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, and the Coast Guard Women’s

Reserve during the early 1940s.

19

Women were serving in the U.S. military as pilots,

mechanics, and drivers, and also worked in communications, intelligence, and supply.

Civilian American women also supported the war eort through their roles in industrial

factories, captured by the quintessential image of “Rosie the Riveter.”

20, 21

At the end of World

War II, without the need for wartime levels of stang, the size of the military contracted

along with the number and scope of women’s roles; at the end of World War II, only women

with critical skills were being recruited for military service.

22

Throughout the conict, more

than 400,000 women supported the war eort at home and abroad.

23

Three years later in 1948, President Harry Truman drastically changed the U.S. military by

signing the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act, granting women permanent status

in both the regular and Reserve forces.

24, 25

Under this Act, women could compose no

more than 2 percent of the total force, and female ocers were not to exceed 10 percent

of women serving. Service secretaries could discharge female Service members without

cause, and women’s service was restricted; women were not allowed on aircraft or ships

engaged in combat.

26

Less than 1 month later, President Truman signed Executive Order

9981, which ended racial segregation in the U.S. military, allowing women of color equal

access to serve.

27, 28

By the start of the Korean War, approximately 22,000 women were serving in the U.S.

military, 30 percent of whom were in the medical or healthcare eld.

29

While few women

deployed outside of the continental United States during the conict, a total of 120,000

women served during the Korean War.

30

In 1951, during the Korean War, DACOWITS was

established to advise on the recruitment of women into the U.S. military.

31

A notable rst

at the end of the 1950s was the promotion of Anna Der-Vartanian to master chief petty

ocer; she became the rst women in the Military Services promoted to the rank of E-9.

32

Despite these progressive steps toward opening military service for women after World War

5

II, President Truman signed Executive Order 10240 in 1951, which allowed DoD to discharge

women who were pregnant, gave birth during service, or who already had children. This

policy requiring the involuntary separation of women who were pregnant or had children

persisted until 1975.

33

The All-Volunteer Force and Women’s Admittance to Military

Service Academies

During the course of the Vietnam War, approximately

7,000 servicewomen served in Southeast Asia; 8 died

in the line of duty, including 1 woman who was killed

by enemy re.

34

Modications to the Women’s Armed

Services Integration Act in 1967 lifted the restriction

on women composing more than 2 percent of military

personnel, which allowed women to reach more senior

ocer ranks for the rst time.

35

Brigadier General Anna

Mae Hays, who began her service in 1942 as an Army

nurse, became the rst woman general ocer in the

Military Services in 1970.

36

In 1973, the U.S. military ended

conscription, becoming an All-Volunteer Force. This

signicant change to the structure of military stang

necessitated a greater need for the recruitment of and

reliance on women because there were not enough

qualied male volunteers to meet the demand for military service.

37

The 1970s also

opened the door for women to access additional training and professional development

opportunities, the Reserve Ocers’ Training Corps (ROTC), and the Military Service

Academies (MSAs). In 1976, President Gerald Ford signed a law allowing women to enter

the MSAs,

38

the rst classes to include women graduated in 1980. Shortly thereafter women

gained recognition as top graduates at each MSA. These women included the rst female

top graduate at the Naval Academy in 1984,

39

at the Coast Guard Academy in 1985,

40

and at

the Air Force Academy in 1986,

41

and the rst female brigade commander and rst female

captain at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1989.

42

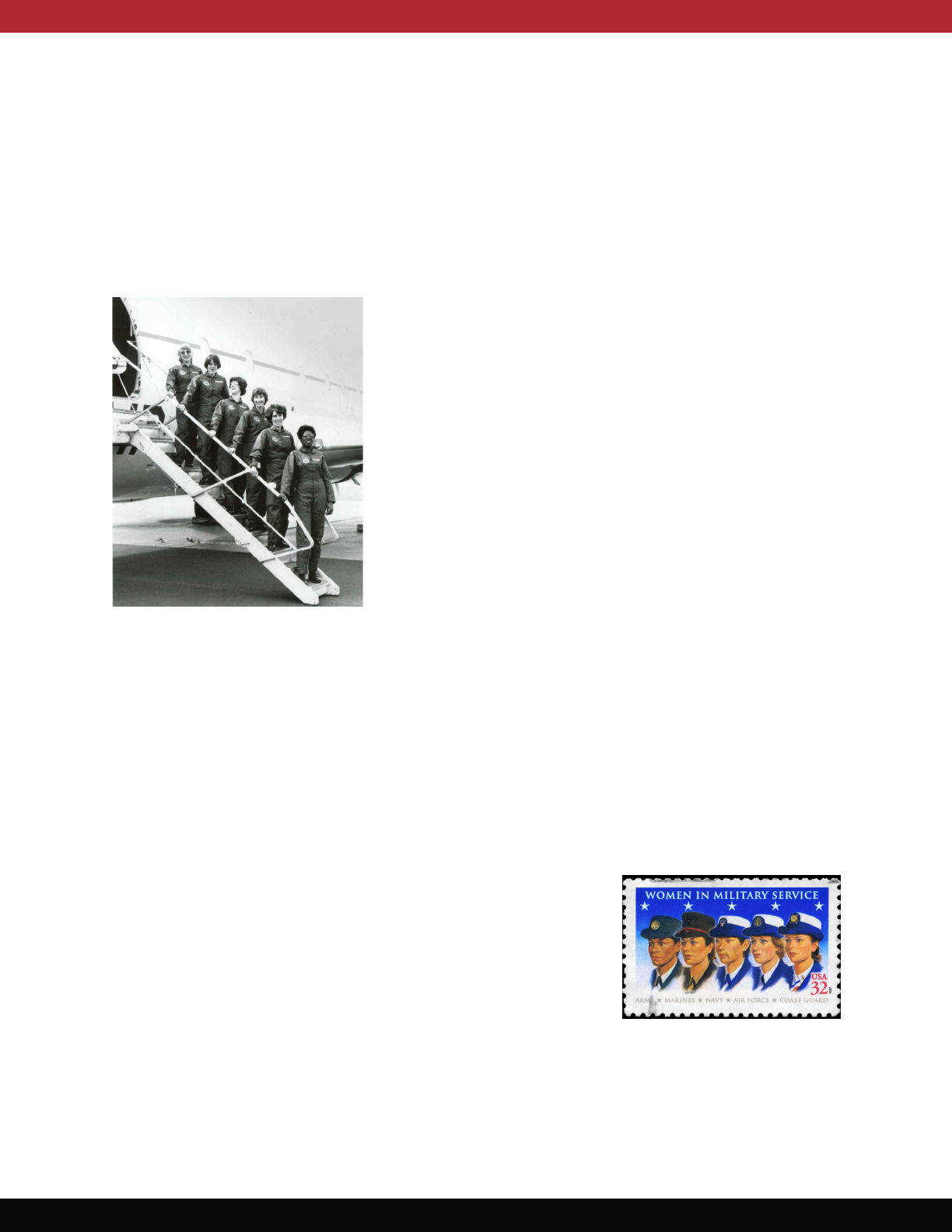

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, women began

promoting to leadership positions, and for the rst time held

command-level roles in noncombat elds that included

medical professionals, chaplains, pilots, boom operators, air

crew members, embassy guards, and ocers in charge of

a vessel. During the 1980s and 1990s, women continued

to gain access to new career elds involved with combat to

some degree, which included positions surrounding combat

missions and serving on combat ships. The Persian Gulf War

(1990–1991) had the largest wartime deployment of women

in the history of the U.S. military up until that point, with more

than 41,000 women serving in Kuwait.

43

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

This 1997 stamp was issued at the

dedication of the Women in Military

Service for America Memorial at

Arlington National Cemetery in

Arlington, Virginia.

6

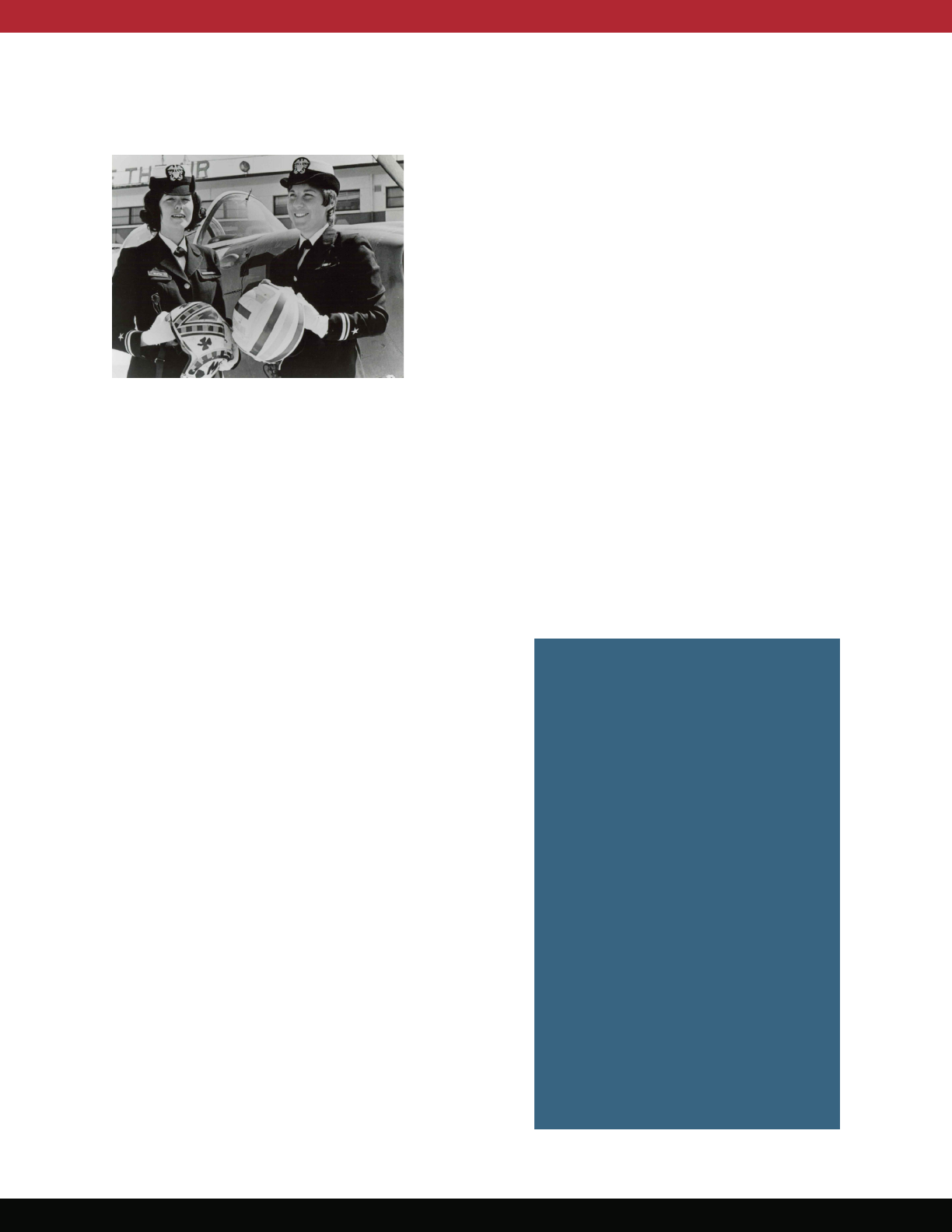

Expansion of Combat Roles for Women

In 1993, then-Secretary of Defense Les Aspen lifted

restrictions to allow women to y combat aircraft

for the rst time.

44

The following year, women

were permitted to serve on most Navy combatant

ships, providing greater opportunities for women’s

leadership and promotion.

45

Despite these legal

changes bringing greater combat opportunities

for women, in 1994, DoD restricted women’s

engagement with ground combat service below

the brigade level.

46

Throughout the 1990s, women

continued to ll mission-critical roles in military

engagements that included Operation Desert Storm, during which female ghter pilots ew

combat aircraft on combat missions for the rst time.

47

U.S. involvement in Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), which began in 2001, and

Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), which began in 2003, changed the way women interacted

with direct combat because of the erasure of the traditional battleeld and the wide range

of roles women served. Women accounted for greater than 10 percent of the more than

2.7 million Service members who deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan from 2001 to 2014.

48, 49

Women were not allowed to serve in direct action combat units but did serve in supporting

units.

50

Because of the nontraditional battleelds of Iraq

and Afghanistan, support units were often in close

proximity to active engagements, which resulted

in higher than expected fatalities among female

Service members. During these operations a

greater relative percentage of women than men

were wounded and later died: 35.9 percent of

women (19) versus 17.0 percent of men (793) in

OIF, and 14.5 percent of women (103) versus 12.0

percent of men (4,226) in OEF.

51

Because of the

nature of the ghting in Iraq and Afghanistan

and women’s contributions during this time,

DoD reassessed the denition of direct ground

combat.

55

In 2010, the Navy announced it would

begin allowing women to serve on nuclear

submarines. Female ocers were assigned to

submarines starting in 2011, and enlisted women

began serving on submarines in 2015.

56

The 2010s saw historic expansions in women’s

opportunities to formally serve in combat. In 2013,

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

Women Were Prisoners of War

(POWs) Before Being Authorized

to Serve in Combat

¡ World War II: Sixty-seven Army

nurses were held as POWs for

2½ years after being captured by

the Japanese in the Philippines. A

second group of 11 Navy nurses were

captured in the Philippines and held

for 3 years. Five Navy nurses were

captured by the Japanese in Guam

and held for 5 months.

¡ Gulf War: Two female Service

members were taken prisoner during

Operation Desert Shield and Desert

Storm.

¡ Iraq War: Three female Service

members became POWs during the

rst days of the War in Iraq supporting

Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Sources: Women in Military Service for

American Memorial Foundation, n.d.

52

Naval

History and Heritage Command, 2017

53

Army.mil Features, n.d.

54

7

following a unanimous recommendation by the Joint Chiefs of Sta, then-Secretary of

Defense Leon Panetta lifted the ban on women participating in the ground Services.

57

As

a result of this policy change, military occupations could remain closed to women only

by exception and only if approved by the Secretary of Defense.

58

That same year, the rst

Marine Lioness team (the precursor to female engagement teams) formed and deployed

to Iraq. These female teams were focused on developing “trust-based and enduring

relationships” with the Iraqi women they encountered on their patrols.

59, 60

These teams

later deployed to Afghanistan and allowed servicewomen to work with Afghan women

and gather critical information in support of the mission. In 2015, then-Secretary of Defense

Ashton Carter announced women would be permitted to apply for all combat units and

positions without exception starting January 1, 2016.

61

This decision mandated each Military

Service develop a plan to ensure women were fully integrated into combat roles deliberately

and methodically.

62

Women in the Military Today

As of 2020, women have served in some of

the most senior roles in the Military Services—

as four-star generals, Vice Chief of Naval

Operations, Chief Master Sergeant of the Air

Force, Chief of the Naval Reserve, Commander

of a Combatant Command, Acting Commanding

General of the United States Army Forces

Command, among others. As of 2019, women

represented 17 percent of the U.S. military,

63

and

as of 2015, approximately 9 percent of the U.S.

veteran population.

64

While substantial progress

has been made toward gender integration, there

is still more to be done. Congress and DoD

continue to make headway to promote and realize full gender integration within the Military

Services, which now include the newly created U.S. Space Force. With the introduction of

this new branch, the U.S. military has a rare opportunity to create a gender-inclusive and

integrated Service at its inception.

U.S. Air Force Gen. Jacqueline D. Van Ovost, Air Mobility

Command commander, speaks with Col. Lee Merkle,

349th Air Mobility Wing commander, during a mission

brieng at 349th Air Mobility Wing Headquarters,

Travis Air Force Base, California, Sept. 1, 2020. Van

Ovost took time to visit Air Force Reserve Command’s

largest wing during her rst visit to Travis as AMC

commander.

8

Chapter 3. History of DACOWITS,

1951 to Present

DACOWITS was established in 1951 by then-

Secretary of Defense George C. Marshall. The

Committee is authorized under the provisions

of Public Law 92–463, the Federal Advisory

Committee Act,

66

which requires all Federal

Advisory Committees to maintain and renew

charters on a biannual basis, to include

information such as the committee’s objectives,

supporting agency, estimated operating costs,

and more.

67

Throughout its history, the Committee has been composed of appointed

civilians who are tasked with providing advice and recommendations about women’s

service to the Secretary of Defense.

68, ii 2

The Committee’s original purpose was

to increase the recruitment of women in

the wake of the 1948 Women’s Armed

Services Integration Act, which allowed

women’s service in the regular active

peacetime forces. At the Committee’s

rst meeting in September 1951, rapid

recruitment of women was the main

focus. The Committee identied a

lofty goal—recruiting 80,000 women

into the Military Services within 10

months—a greater number than was

achieved in World War II. A need for additional nurses was also discussed.

69v

During its nearly 70-year history, DACOWITS’ mission has evolved. Today, the Committee

provides advice and recommendations to the SecDef through the Under Secretary of

Defense for Personnel and USD(P&R) on matters associated with the recruitment, retention,

employment, integration, well-being, and treatment of women in the Military Services. Many

other aspects of DACOWITS, such as its objectives and membership requirements, have

also evolved since its inception in 1951. These changes are discussed in the sections that

follow, including Committee size and membership, organizational structure, Committee

guidance, areas of focus, installation visits, and support of other DoD activities. One

aspect that has remained consistent throughout DACOWITS’ 70-year history is the need

ii

The information in this chapter is drawn from the internal DACOWITS document “DACOWITS History and

Accomplishments, 1951–2011” unless otherwise specied.

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

“American women can well be the margin

between victory and defeat if only their utilization

is planned intelligently in connection with

manpower.”

—Statement from Col Mary A. Hallaren at the rst

DACOWITS convening. Col Hallaren was the former

director of the Women’s Army Corps and the rst

woman to ocially join the Army.

Source: New York Times, 1951

65

9

recognized by DoD for a Federal Advisory Committee dedicated to providing robust

recommendations on pertinent issues involving servicewomen.

Committee Size and Membership

The composition of DACOWITS—the number of

members and their term limits—has uctuated

over time. The size of the Committee is dictated

by its charter. In its rst year, DACOWITS was

composed of 50 civilian members. Over the

years, the maximum permitted number of

members has ranged from 40 (2000–2002) to

15 (2008–2010). Throughout the Committee’s

history, members have been permitted to

serve 1- to 4-year terms. In 1978, the Committee

welcomed its rst male members.

Currently, the Committee may consist of no more than 20 members, who are drawn from

a range of professional backgrounds and are selected for their experience with military

service or women’s workforce issues. The Committee includes male and female members

with and without military experience. For those with prior military service experience, the

members represent both ocers and enlisted personnel and all Military Service branches.

The current members include prominent civilian women and men from academic, industry,

public service, and other professions.

The Committee has also been led by an esteemed list of chairs (see Table 3.1).

Table 3.1. DACOWITS Chairs, 1951 to Present

Term Chair

1951 Mrs. Mary Pillsbury Lord

1952–1953 Ms. Lena Ebeling

1954 Mrs. Eve Rawlinson Lee

1955 Mrs. Evelyn Crowther

1956–1957 Ms. Margaret Divver

1958 Mrs. Murray Pearce Hurley

1959 Ms. Janet P. Tourtellotte

1960 Mrs. Margaret Drexel Biddle

1961 Mrs. Lucia Myers

1962 Mrs. Nona Quarles

1963 Ms. Margaret J. Gilkey

1964 Mrs. Betty M. Hayenga

1965 Mrs. Elinor Guggenheimer

1966 Mrs. Agnes O’Brien Smith

1967 Dr. Minnie C. Miles

DACOWITS’ 2019 installation visit to Davis-Monthan

Air Base. Photo from the DACOWITS archives

10

Term Chair

1968 Dr. Geraldine P. Woods

1969 Dr. Hester Turner

1970 Dr. Majorie S. Dunlap

1971 Mrs. Helen K. Leslie

1972 Mrs. Estelle M. Stacy

1973 Mrs. Fran A. Harris

1974 Mrs. Wilma C. Rogalin

1975 Mrs. Nita D. Veneman

1976 Mrs. Judith Nixon Turnbull

1977–1978 Mrs. Piilani C. Desha

1979–1980 Mrs. Sally K. Richardson

1981 Dr. Gloria D. Scott

1982 Mrs. Maria Elena Torralva

1983 Dr. Mary Evelyn Blagg Huey

1984 Mrs. Anne L. Schulze

1985 Ms. Constance B. Newman

1986–1988 Dr. Jacquelyn K. Davis

1989 Dr. Connie S. Lee

1990 Ms. Meredith A. Neizer

1991 Ms. Becky Costantino

1992 Mrs. Jean Appleby Jackson

1993 Ms. Ellen P. Murdoch

1994 Mrs. Wilma Powell

1995 Ms. Sue Ann Tempero

1996 Mrs. Holly K. Hemphill

1997 Dr. Judith Youngman

1998 Ms. Elizabeth T. Bilby

1999 Ms. Mary Wamsley

2000–2001 Ms. Vickie L. McCall

2002–2005 LtGen (Retired) Carol A. Mutter, U.S. Marine Corps

2006–2009 Mrs. Mary Nelson

2010–2011 LTG (Retired) Claudia J. Kennedy, U.S. Army

2012–2014 Mrs. Holly K. Hemphill

2014–2016 LtGen (Retired) Frances Wilson, U.S. Marine Corps

2016–2021 Gen (Retired) Janet C. Wolfenbarger, U.S. Air Force

Committee Organizational Structure

Historically, DACOWITS has been organized into subgroups (sometimes referred to as

task forces, working groups, or subcommittees) to divide responsibilities among members

and ensure adequate attention is paid to the Committee’s various topics of interest.

While subgroups focus on particular topics or areas, the entire Committee votes on all

recommendations delivered to the Secretary of Defense. At its establishment in 1951,

11

DACOWITS was composed of ve working

groups: training and education, housing

and welfare, utilization and career planning,

health and nutrition, and recruiting and public

information. In the late 1970s and early 1980s,

the Committee formed unique task forces

to address emerging issues, such as a legal

and legislative task force in 1979 to focus on

issues pending before Congress (e.g., whether

to require women to register for the Selective

Service).

70

In 1982, the Committee formed one

task force to focus on the MSAs and another to

focus on ROTC. The Committee also created task forces centered around internal issues

such as public relations (in 1980) and new member orientation (in 1982). From 2010 to

2015, the Committee was organized into two subcommittees: wellness and assignments.

Since 2016, the Committee has been structured into three subcommittees: recruitment and

retention, employment and integration, and well-being and treatment. Under the current

structure, each subcommittee has a lead and a subset of members who concentrate their

eorts on topics assigned to the subcommittee.

Areas of Focus Over the Years

Upon its establishment in 1951, DACOWITS’ primary goal was to advise the Secretary of

Defense on strategies to improve the recruitment of women in the U.S. military during the

Korean War. However, the Committee’s mission changed just 2 years after establishment

to focus on promoting military service as an acceptable career path for women. DACOWITS

has consistently adapted over time to ensure the Committee is aligned to address relevant

and timely topic areas. Since 2002, DoD’s Oce of the Secretary of Defense has provided

annual guidance to the Committee on topic areas to investigate during a given year.

The number of topics DACOWITS

has been directed to review on an

annual basis has varied over time

as well. For example, in 2003, DoD

directed the Committee to investigate

a variety of topics, which included

retention of female ocers, support

during deployment, and healthcare—

particularly obstetrics and gynecology

(OB/GYN) care.

71

However, in 2006,

DoD directed DACOWITS to focus

its eorts on one topic, the “representation and advancement of female ocers among

lawyers, clergy and doctors in all branches of the Services.”

72

In 2020, the Committee

studied a variety of issues, which include: dual-military co-location policies, marketing

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

12

strategies, retention and exit surveys, women in

aviation, women in space, gender implementation

plans, the Army Combat Fitness Test, the eect of

grooming standards on women’s health, primary

caregiver leave, and caregiver sabbaticals. In

addition to annual topic areas of focus, DACOWITS

has also established themes in certain years

to guide its eorts, such as “Recall to Duty-

1971” and “Salute to Women in the Services”

in 1971—the Committee’s 20th anniversary

year—and “Changing Roles of Women in the

Armed Forces” in 1977. The recommendations

DACOWITS makes each year are directly related to the topics it has studied. Finally, some

topics that originally fell under DACOWITS’ purview have been taken over by new Federal

Advisory Committees—for example, the DoD Military Family Readiness Council, which was

established in 2008, and the Defense Advisory Committee on Investigation, Prosecution,

and Defense of Sexual Assault in the Armed Forces, which was established in 2016.

73

An overview of the breadth of topics DACOWITS recommendations have addressed are

presented in Chapter 4.

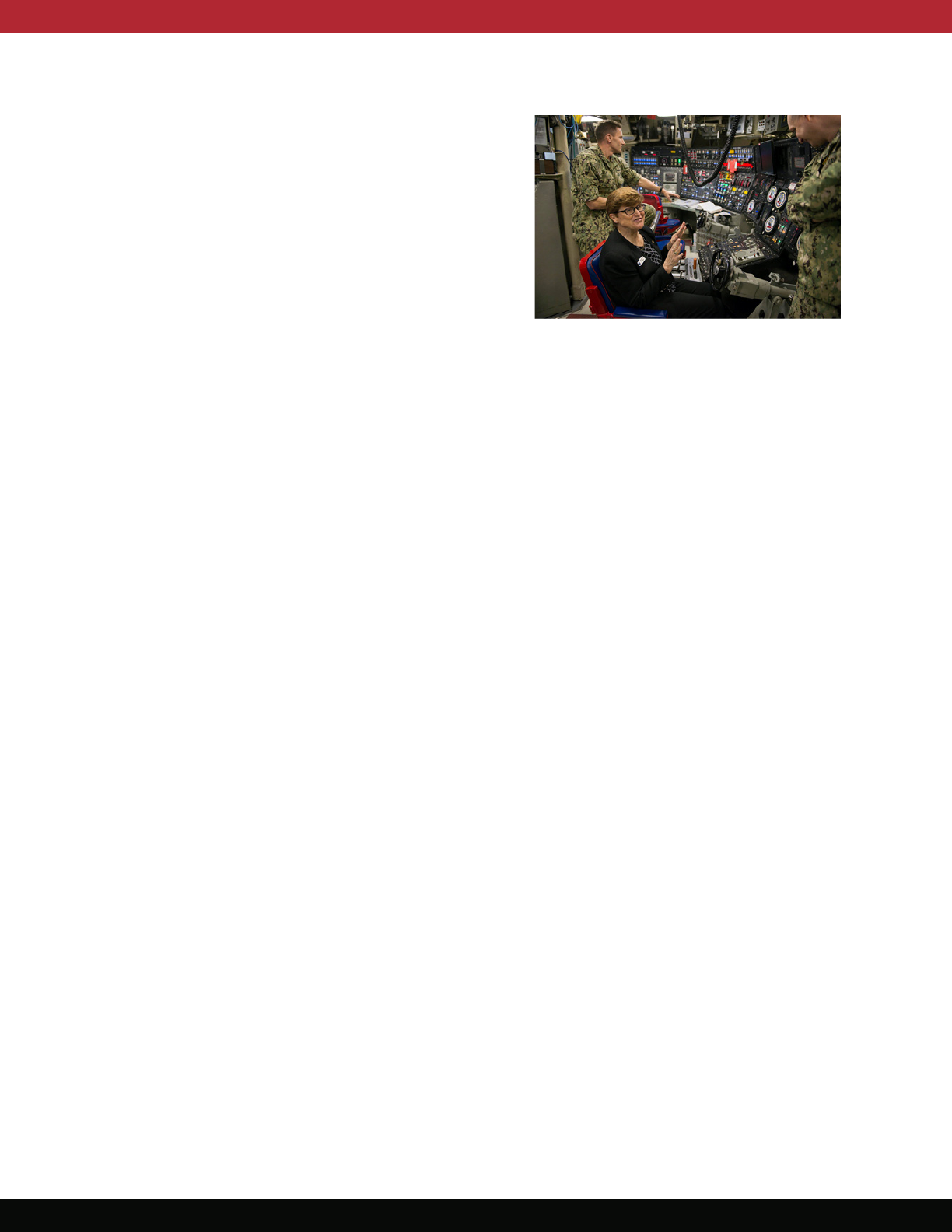

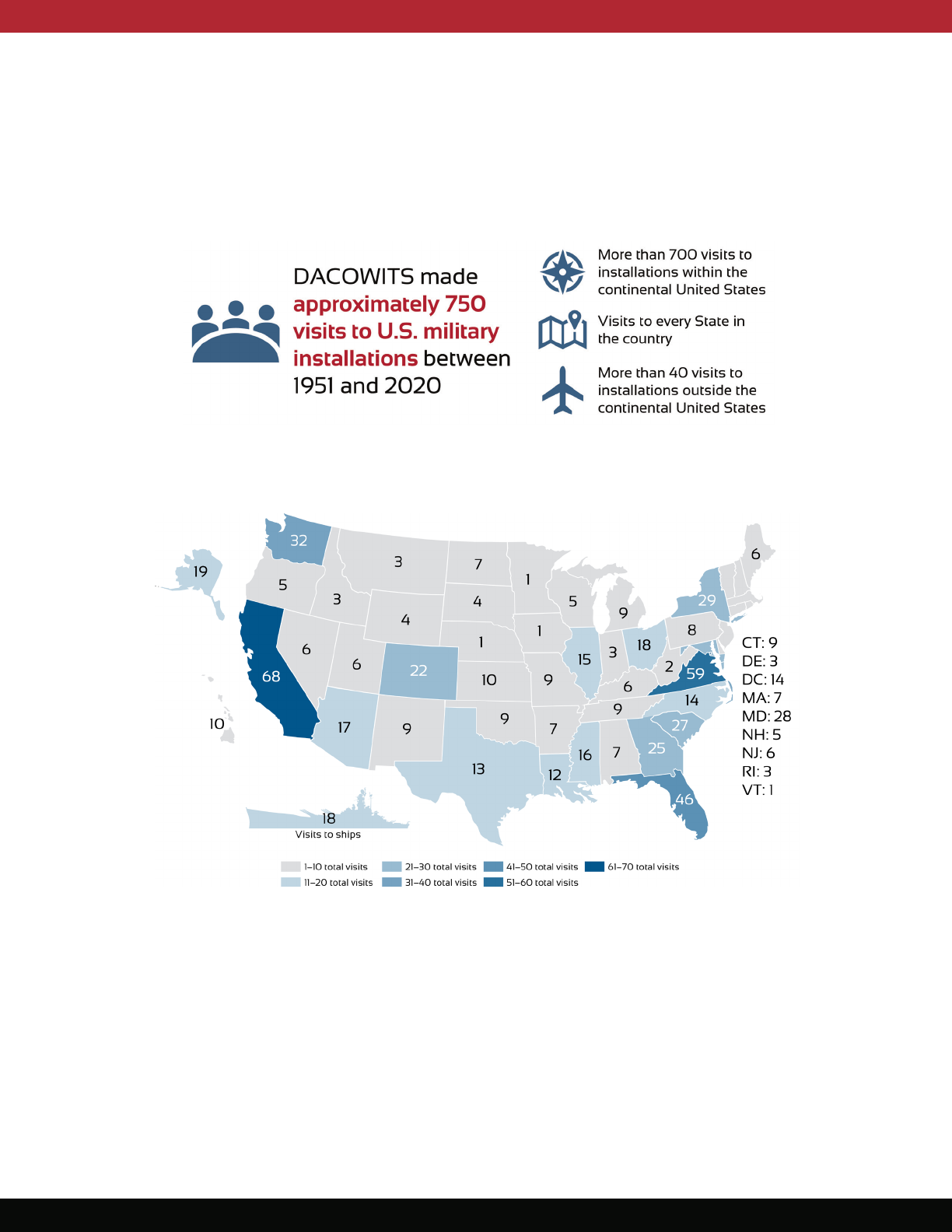

Installation Visits

A major tenet of DACOWITS’ work throughout its history has been directly engaging

Service members during in-person visits to U.S. military installations. From 1951 to 2020,

DACOWITS made approximately 750 installation visits to obtain rsthand information from

both male and female Service members on topics of interest to the Committee (see Figures

3.1, 3.2, and 3.3). During these visits, the Committee interacted with hundreds of Service

members each year. The type of information gathered during these visits has evolved

over time. Over the years, DACOWITS has moved from informal reporting of member

observations to formal data collection through structured focus groups and rigorous

qualitative data analysis. Some notable installation visit milestones follow:

¡ 1978: DACOWITS made its rst formal Coast Guard visits.

¡ 1986: DACOWITS made its rst visits overseas to Germany and the United Kingdom

to engage with deployed Service members.

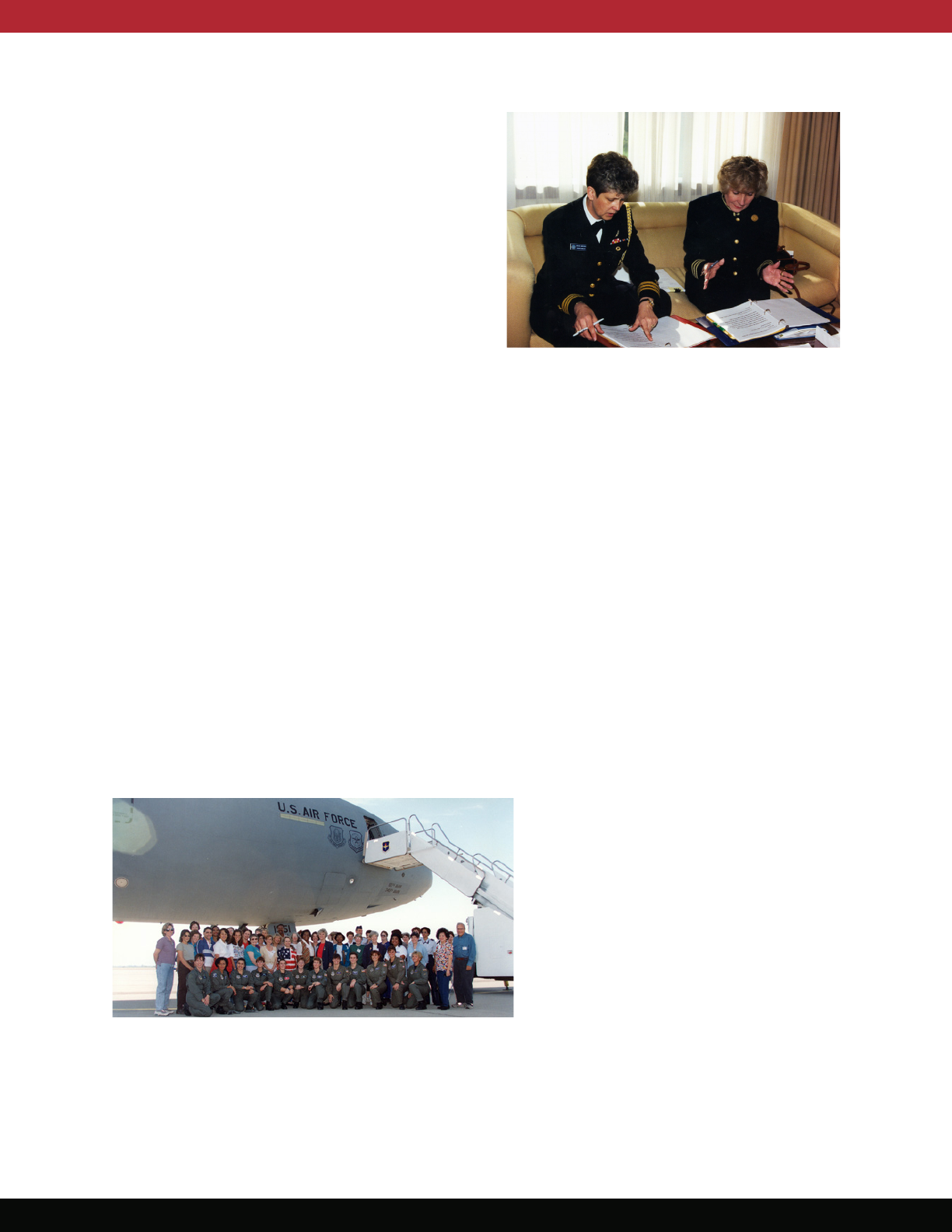

¡ 1996 and 2000: The DACOWITS Executive Committee and sta made visits

to Jordan to fulll an invitation from Lieutenant Colonel (then Major) Her Royal

Highness Princess Aisha Bint Al Hussein to meet with personnel of the Directorate

of Women’s Aairs, Jordan Armed Forces.

¡ 2005, 2007, 2008, and 2009: DACOWITS completed virtual site visits to Iraq and

Afghanistan via video teleconferences.

DACOWITS’ 2019 Installation visit to Naval

Submarine Base Kitsap. Photo from the DACOWITS

archives

13

Currently, DACOWITS conducts approximately 10 installation visits per year, which include

rigorous data collection through focus groups and mini-surveys, meetings with senior

leaders and commanders, informal gatherings with Service members, and installation tours

that allow members to observe the spaces where servicewomen work and live.

Figure 3.1 Summary of DACOWITS Installation Visits, 1951 to 2020

Figure 3.2. Number of DACOWITS Installation Visits by State, 1951 to 2020

Notes:

CT = Connecticut; DE = Delaware; DC = District of Columbia; MA = Massachusetts; MD = Maryland; NH = New

Hampshire; NJ = New Jersey; RI = Rhode Island; VT = Vermont

14

Figure 3.3. Countries Visited by DACOWITS, 1951 to 2020

Guidance for Committee Members

DACOWITS has regularly prioritized the

development of internal resources and

guidelines to support its members and

promote consistency among their eorts.

In 1979, DACOWITS approved revised

operating guidelines that resulted in

the implementation of a new member

orientation program and increased

information-gathering responsibilities for

Committee members, which included a

minimum of two self-coordinated military

installation visits per year and expanded

expectations around Committee member engagement with information sources. In 1985,

DACOWITS developed a handbook and installation visit guide to clarify the Committee’s

operating guidelines and assist members with planning and conducting their visits to

military installations. The current chair has prioritized the member handbook by ensuring it

is current and comprehensive and able to serve as a reference document for all Committee

activities and business.

DACOWITS has also recognized the importance of consistently reviewing its structure,

mission, and guiding principles to ensure they maintain their relevance over time. For

its 50th anniversary in 2001, the Committee established a subcommittee to examine

DACOWITS’ mission, goals and objectives, technical and structural systems, decision-

making processes, and personnel systems.

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

15

DACOWITS Support of Other DoD Activities

Historically, DACOWITS members have

engaged in various DoD activities outside

the scope of the Committee’s eorts to

advise the Secretary of Defense. Members of

the Committee have participated in a variety

of DoD celebrations and ceremonies to help

increase public awareness of DACOWITS.

These events have included the 1952 White

House ceremony to commemorate the

rst issue of a postage stamp honoring

women in the U.S. military; the 1995

ceremony to break ground for the Women

in Military Service for America Memorial (also known as the Women’s Memorial); and the

2001 ceremony at the Army Women’s Museum in Fort Lee, Virginia, to commemorate

DACOWITS’ rst installation visit to the Women’s Army Corps Training Center in 1951. More

recently, the Committee has continued to publicly celebrate and support women in the

Military Services by cohosting a 2017 event with the U.S. Department of Veterans Aairs’

Center for Women Veterans to celebrate Loretta P. Walsh, the rst woman to enlist into U.S.

military service, who joined March 21, 1917.

74

DACOWITS’ eorts have also resulted in the development of other DoD task forces.

These have included the DoD Task Force on Women in the Military, established in 1987

in response to DACOWITS recommendations, and the DoD Quality of Life Task Force,

established in 1994. As evidenced by the activities described earlier in this section,

Committee members have prioritized participating in supplemental activities focused

on women’s experiences in the Military Services to build awareness and celebrate the

accomplishments of such women, and they continue to do so.

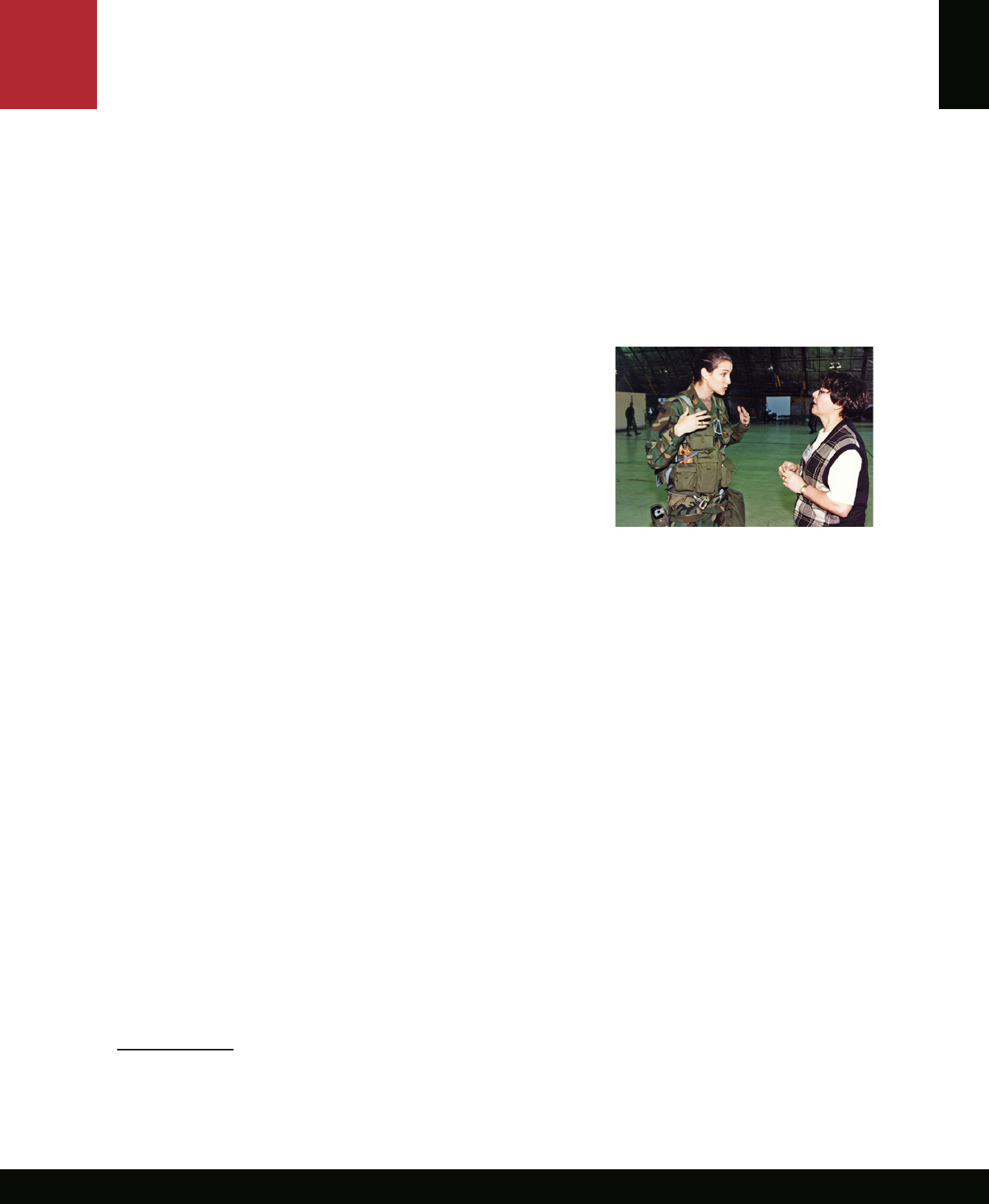

In 2020, DACOWITS commemorated the 40th anniversary of

the rst female graduates of the U.S. Air Force Academy, the

U.S. Naval Academy, and the U.S Military Academy at West

Point. Three members of those graduating classes have served

on DACOWITS-- MAJ (Ret) Priscilla Locke, Ms. Janie Mines, and

current DACOWITS Chair Gen (Ret.) Janet Wolfenbarger.

DACOWITS members who were in the rst class of female graduates

of the Military Service Academies pictured with the former DACOWITS

Military Director and Designated Federal Ofcer, Colonel Toya Davis

(second from right). Source: Cronk, 2020.

Celebrating the 40th Anniversary of the First Female Graduates

of Military Service Academies

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

16

Looking Ahead: The Future of DACOWITS

Building on its legacy and dedicated history,

DACOWITS continues to serve by providing

independent advice and recommendations

to the Secretary of Defense on matters and

policies relating to the recruitment, retention,

employment, integration, well-being, and

treatment of women in the Military Services.

The Committee will continue its work toward

making recommendations to improve

the lives of servicewomen that will have

lasting impacts beyond the current decade.

Although DACOWITS focuses its eorts on

servicewomen, all Service members benet

when the Committee’s recommendations

are implemented. The Committee’s rich history and sustained eort live on as its members

rigorously study relevant topics of concern to DoD, conduct installation visits, and determine

recommendations that will help guide the future of the U.S. military for years to come.

DACOWITS’ 2019 installation visit to Joint Base Elmendorf-

Richardson. Photo from the DACOWITS archives

17

Chapter 4. Analysis of DACOWITS

Recommendations, 1951 to Present

S

ince its inception in 1951, DACOWITS has made more than 1,000 recommendations

on dozens of topics and themes. As of 2019, 97 percent of the recommendations

iii

made have been fully or partially adopted by DoD.

75

The following chapter provides

an analysis of the Committee’s recommendations over time, including the research team’s

methodology and brief discussions of the most prevalent themes.

Trends in DACOWITS Recommendations

Based on a review of DACOWITS meeting minutes,

reports, and internal documents the Committee made a

total of 1,062 recommendations between 1967 and

2020.

iv3

In addition to standard recommendations,

continuing concerns and commendations were also

included in the analysis; these three types of actions are

referred to collectively as recommendations in this report.

Recommendation Analysis Methods

The research team used qualitative methods to analyze the more than 1,000

recommendations DACOWITS made from 1967 to 2020. As outlined in this section, the

research team coded each recommendation by theme (e.g., benets and entitlements,

career progression, family support); type (standard recommendations, commendations, or

continuing concerns); purpose (e.g., program resources and/or support, policy change); and

the target population or audience (e.g., all the Military Services, one specic Service) for the

recommendation.

Coding Recommendations by Theme

The research team rst chronologically organized the recommendations and coded each

observation by general themes and subthemes. General themes were initially derived from

topics highlighted in past DACOWITS annual reports available on the DACOWITS website.

76

Throughout the coding process, the themes were rened and subthemes introduced

to allow for greater specicity in coding and later analysis. Each recommendation was

coded with at least one theme. In cases when a recommendation explicitly pertained to

more than one theme, the two most prevalent themes were coded. Out of a total of 1,062

recommendations, 763 were coded with 1 theme, and 299 were coded with 2 themes.

iii

Recommendations made prior to 2018

iv

Recommendations made prior to 1967 are accessible only by manually retrieving them from the National Archives.

Because recommendations made prior to 1967 were not readily accessible, they were not included in the analysis.

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

18

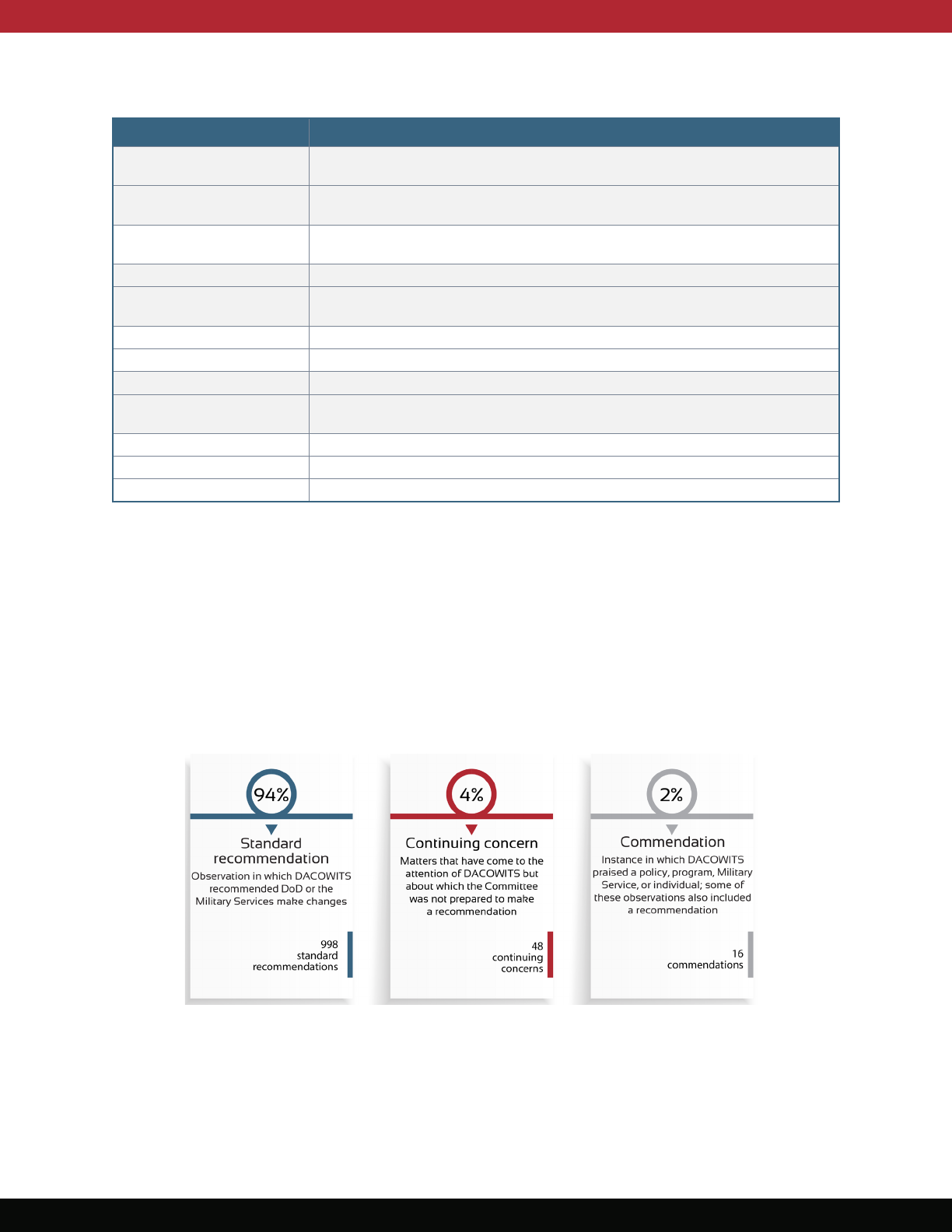

Coding Recommendations by Type

In addition to themes, the research team designated each observation as a standard

recommendation (observation in which DACOWITS recommended DoD or the Military

Services make changes); continuing concern (matter that came to the attention of

DACOWITS but about which the Committee was not prepared to make a recommendation),

or commendation (praise by DACOWITS for a policy, program, Military Service, or individual).

Some commendations also included a recommendation.

Coding Recommendations by Purpose

The research team identied the purpose of each recommendation. Common purposes

were whether the recommendation pertained to program resources and/or support,

research, symbolic recognition, internal DACOWITS activity, a policy change, or a legal

change. Any recommendations that did not appropriately t into these categories were

coded as “other.”

Coding Recommendations by Target Entity

The research team identied the target entities or audience toward which each

recommendation was directed—classifying whether the recommendation was intended for

all Military Services, Service specic,

v4

DACOWITS itself, or some other population.

Descriptions of the common themes, types, purposes, and target populations of the

recommendations follow.

Common Themes Addressed in Recommendations

Throughout the years, DACOWITS’ recommendations have addressed a variety of topics

and subtopics. Table 4.1 presents the most common topics of concern for the Committee,

organized alphabetically. The ndings outlining the number of recommendations the

Committee made regarding each topic area are described later in this chapter.

Table 4.1. Common Themes and Subthemes Addressed in DACOWITS

Recommendations, 1967 to 2020

Themes and Subthemes Description

Benets and entitlements Benets, salary, or entitlements received by current or former Service members

Base allowance for quarters Housing allowances

Housing Housing on or o base for Service members

TRICARE Healthcare for Service members

Career progression

Career progression of a Service member, including career planning and

trajectories, transitions and/or assistance related to assignments and

placements, and leadership development

Deployment Transitions related to deployments

v

Recommendations that were directed to two or three Services are included in the Service-specic category.

19

Themes and Subthemes Description

Reintegration Transitions related to reintegration after returning from deployments

Pregnancy status Transitions related to pregnancy status

Transition between Active

and Reserve Components

Transitions related to members of the Reserve or Guard moving to active duty

status or active duty Service members moving to the Reserve or Guard

Veterans

Transitions related to separating from the U.S. military and moving to veteran

status; also includes general recommendations related to veterans

Promotion and/or career

advancement

Career advancement, promotion criteria, and performance evaluations

Enlistment Standards or practices used around enlistment

Leadership development and

representation

Initiatives for leadership or mentoring development, including both individual

members of the U.S. military (developing their personal leadership skills) and the

Military Services’ leadership as a whole (e.g., strengthening ocer training); also

includes diversity (e.g., race, gender, ethnicity) initiatives for underrepresented

leaders, including at the executive/advisory board level

Communication and/or

dissemination

Communication or dissemination of information from the branches or

DoD to Service members and/or civilians; for example, “increase eective

communication”

Education and/or training Education or training

Basic training Basic or recruit training

MSAs Education and trainings conducted at MSAs

Youth programming Education and trainings for children younger than 18

ROTC ROTC or Junior ROTC programs

New training or conferences Creation and/or implementation of new trainings or organization of conferences

Modications to existing

training or conferences

Expanding or modifying existing trainings or conferences

Family support Policies aimed at supporting families and their dependents

Child care Child care

Domestic abuse Domestic abuse

Dual-military couples

Spouses who both are current Service members; includes co-location policies for

such couples

Family leave policies

Parental or family leave policies that allow Service members to take leave when

having/adopting a child

Sabbaticals

Sabbatical programs that allow Service members to take leave to pursue other

areas of life

Gender equality and

integration

Equalizing standards or guidelines for genders, including integrating women

into previously closed positions or units, and barriers preventing full integration;

also includes utilization OR increasing the number/percentage of women in

underrepresented elds

Women in combat Integrating women into previously closed combat positions

Gender bias

Gender bias or sexism involving any prejudice or stereotyping based on gender or

sex

Physical tness standards

Completion, implementation, and components of physical tness tests or

the discussion of physical tness test requirements; body specications,

measurements and scales, and physical ability requirements deemed necessary for

adequate job performance

Uniforms and equipment Uniforms and equipment used by female Service members

Reserve and Guard

components

Reserve or Guard, specically

20

Themes and Subthemes Description

Internal to DACOWITS

DACOWITS processes or the dissemination of information pertaining to

DACOWITS

Marketing and recruitment

Media or programs specically designed to promote a given entity (e.g., the

Military Services) or related to the recruitment of female Service members

Portrayal of female Service

members in media

Depiction and representation of female Service members in the media; e.g., print,

video, television, stamps, radio

Retention Female attrition and retention

Sexual harassment and

sexual assault

Both sexual harassment and sexual assault

Sexual harassment Related to sexual harassment, but not sexual assault

Sexual assault Related to sexual assault, but not sexual harassment

Unit culture and morale Unit culture or morale

Women’s health and well-

being

Women’s health, including reproductive health

Breastfeeding and lactation Breastfeeding and lactation policies, programs, or support

Mental health Mental health, including drug or alcohol abuse and posttraumatic stress

Pregnancy Pregnancy, including postpartum

Notes:

MSA = Military Service Academies

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

77, 78

Common Types of Recommendations

Each recommendation has been designated as a standard recommendation, continuing

concern, or commendation. The denition and prevalence for each recommendation type is

shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1. Definition for Each Type of DACOWITS Recommendation,

and Distribution of Types

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

79, 80

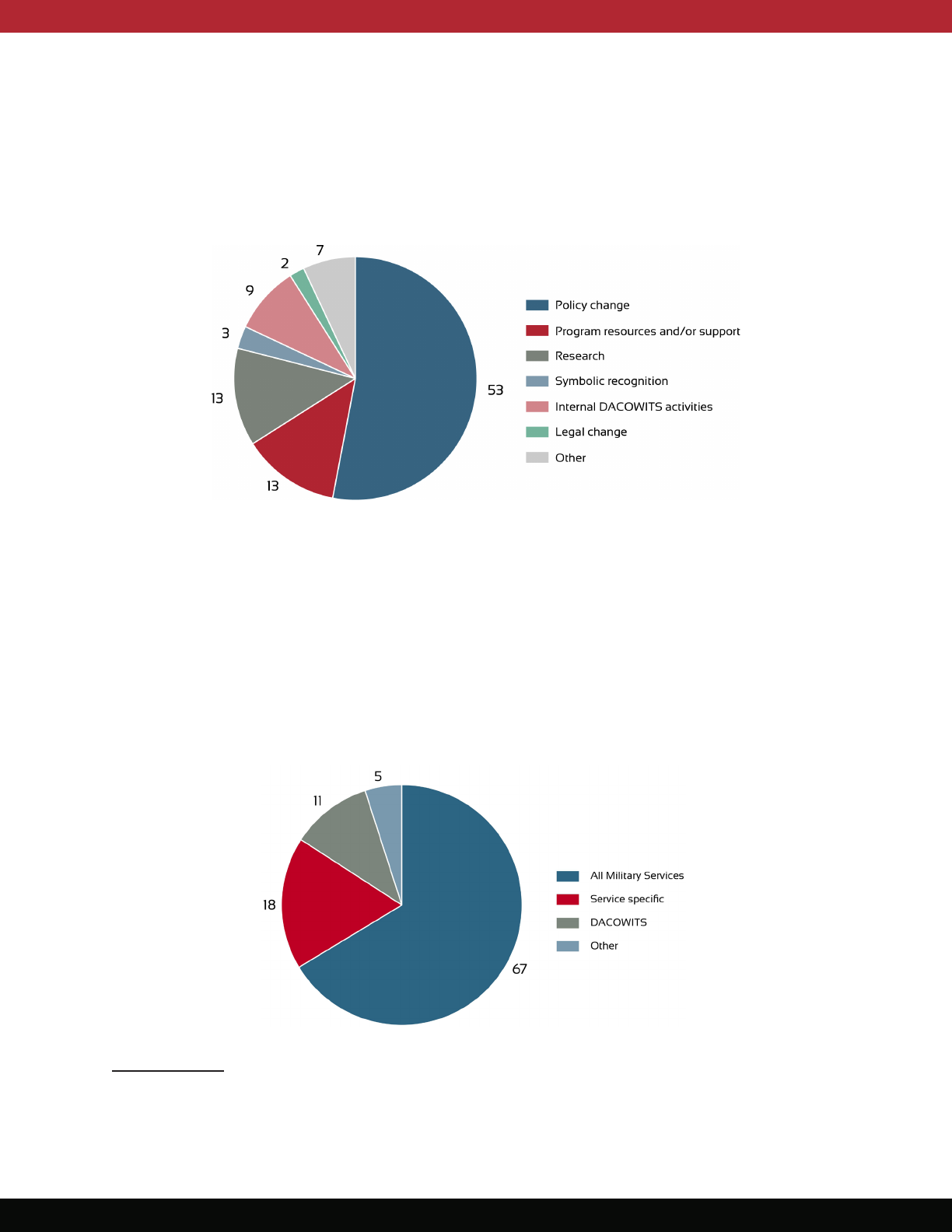

Common Purposes of Recommendations

DACOWITS recommendations served a variety of purposes. The largest category,

representing 53 percent of all recommendations, aimed to enact a policy change. Of

21

the remainder, 13 percent (136 recommendations) pertained to program resources and/

or support; 13 percent (140) pertained to research; 9 percent (99) applied to internal

DACOWITS activities; 3 percent (35) focused on symbolic recognition; 2 percent (16)

pertained to a legal change; and 7 percent (78) were classied as other (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Percentage of DACOWITS Recommendations by Purpose

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

81, 82

Common Target Entities for Recommendations

Each DACOWITS recommendation is directed toward a specic entity tasked with

considering the change proposed by the Committee. Recommendations are directed

toward all the Military Services, a specic Service,

vi5

DACOWITS itself, or some other entity.

Of the 1,062 recommendations analyzed, two-thirds (707, or 67 percent) were directed

to all Military Services; 186 (18 percent) were Service specic; 116 (11 percent) pertained to

DACOWITS; and 53 (5 percent) pertained to another population (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. Percentage of DACOWITS Recommendations by Target Entity

Note: Percentages do not sum to 100 because of rounding.

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

83, 84

vi

Recommendations that were directed to two or three Services are included in the Service specic category.

22

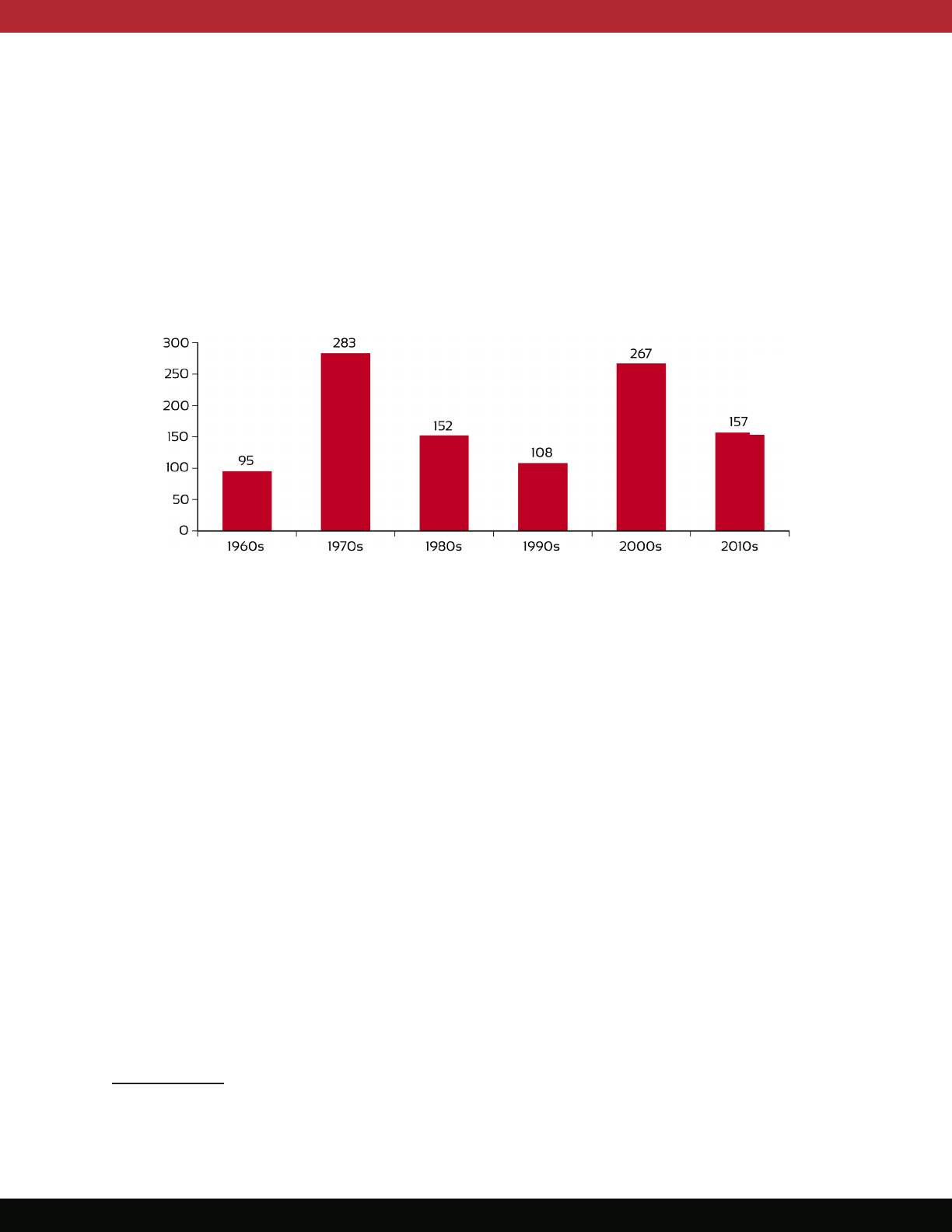

DACOWITS Recommendations Across the Decades

A broad examination of DACOWITS’ work during the past seven decades shows how a

range of factors have inuenced the production of the Committee’s recommendations.

The Committee made the majority of its recommendations during the 1970s and 2000s,

coinciding with the Vietnam War and the transition to an All-Volunteer Force in 1973, and

the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001 and subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (see Figure

4.4).

Figure 4.4. Number of DACOWITS Recommendations by Decade

Note:

*The year 2020 is included in 2010s.

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

85, 86

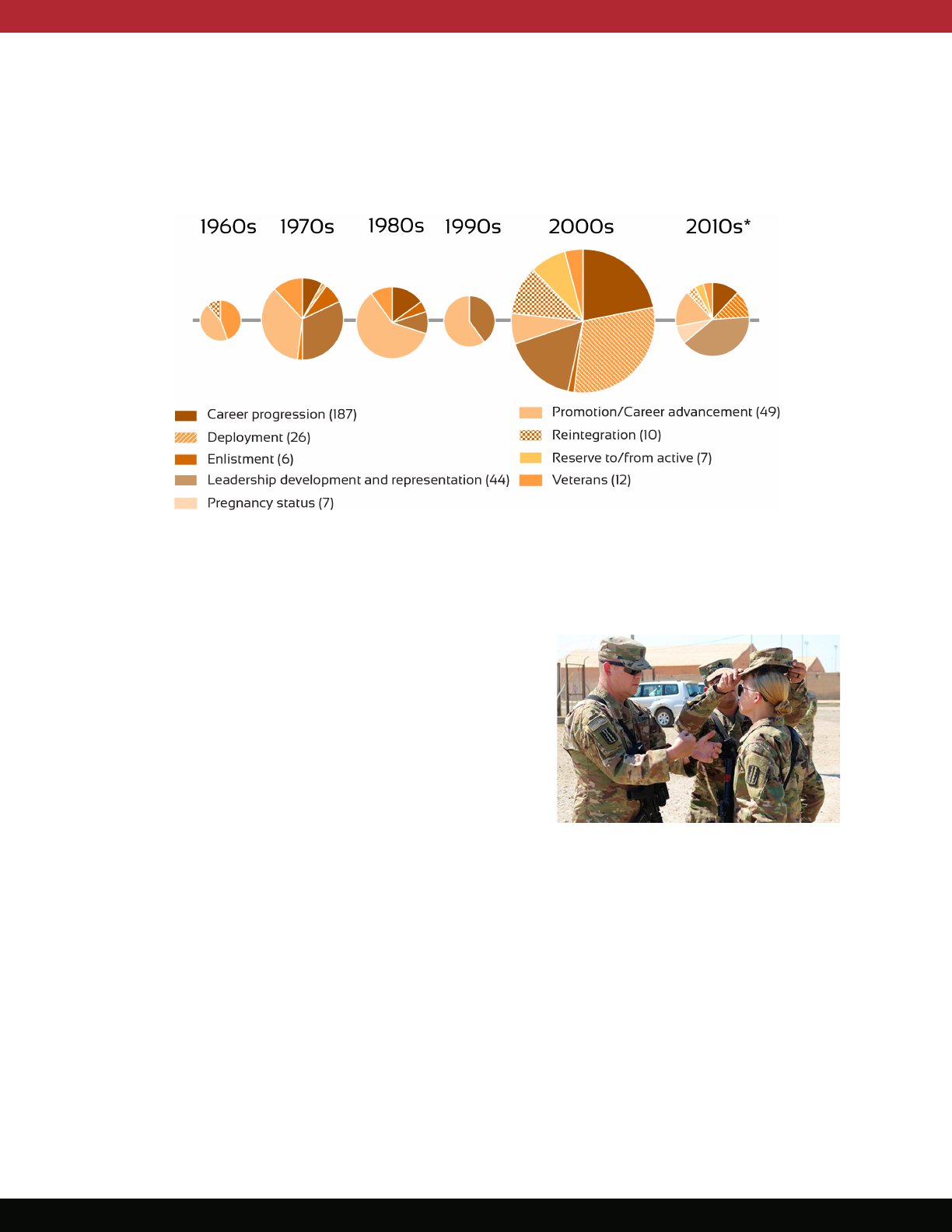

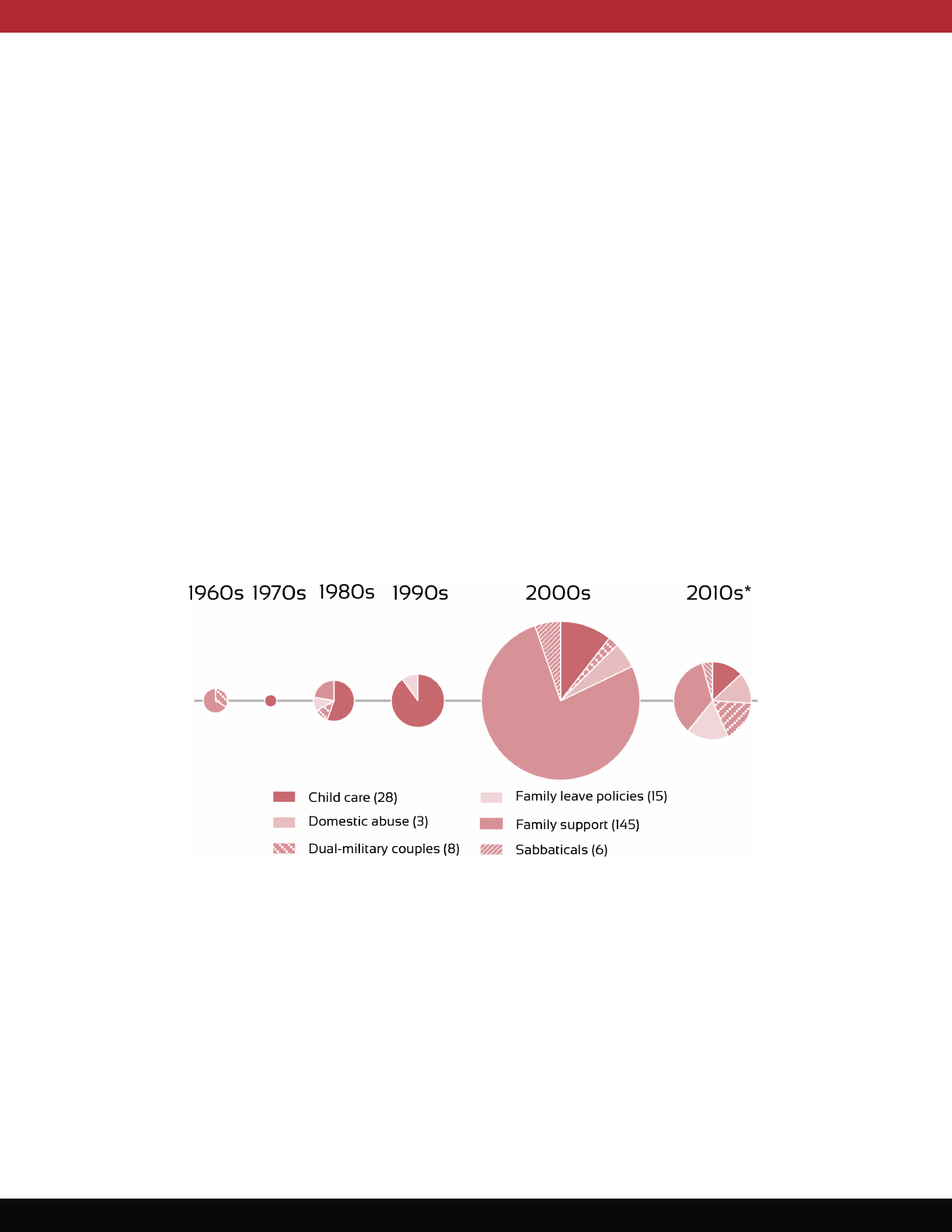

In the 1970s, the Committee focused on recommendations related to gender equality

and integration, followed by recommendations pertaining to benets and entitlements for

current and former Service members, and career progression of Service members. Despite

a consistent decrease in the number of gender equality and integration recommendations

throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the topic remained the Committee’s top priority in the 30

years following the U.S. military’s transition to an All-Volunteer Force. In the 2000s, the

Committee focused its recommendations on family support and career progression, and

in the 2010s, the focus shifted to gender integration and sexual harassment and sexual

assault.

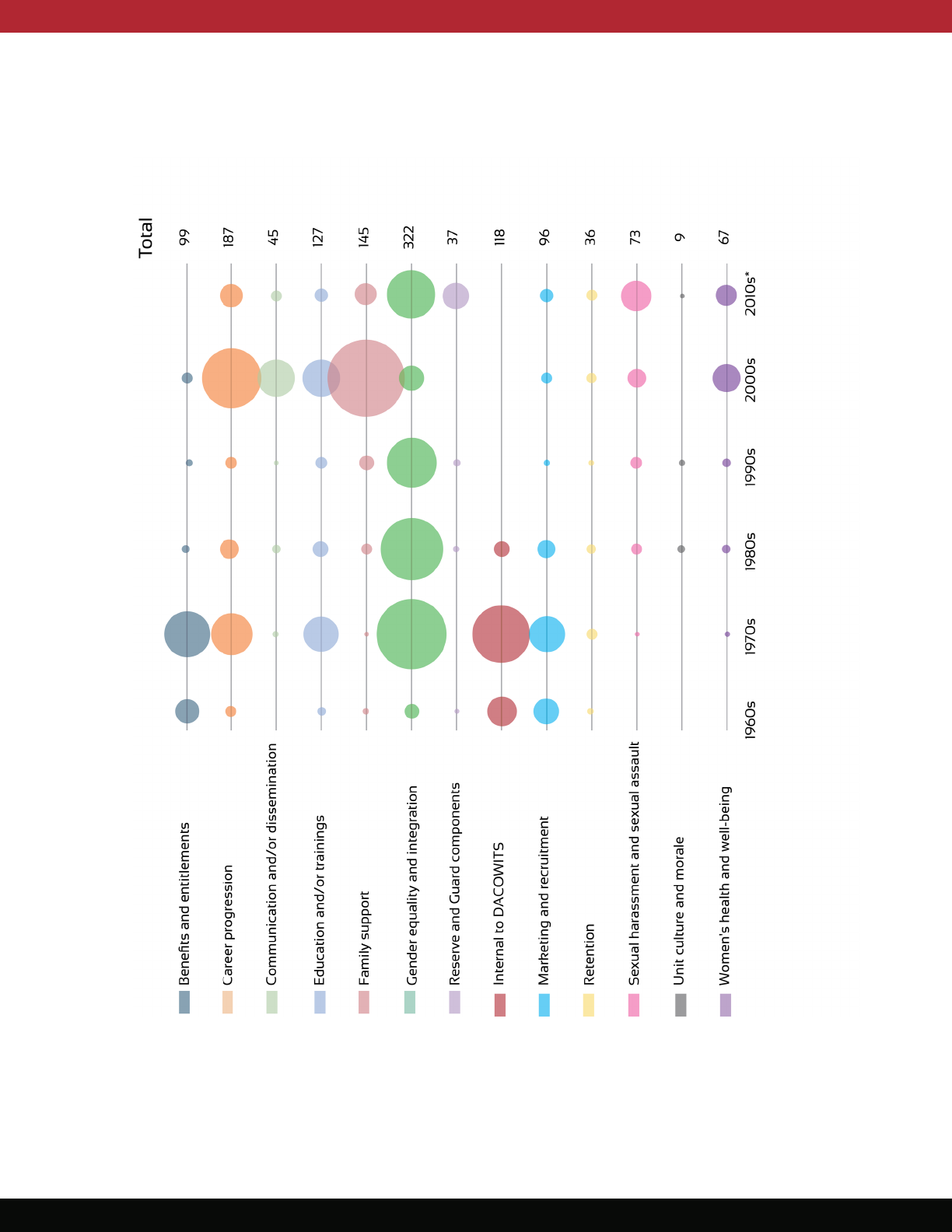

History of DACOWITS Areas of Concern as Reflected in Its

Recommendations

This section presents the common themes and topics addressed by DACOWITS

recommendations from 1951 to the present.

vii6

DACOWITS recommendations fell into 13

broad topics (see Figure 4.5, which is ordered alphabetically). Each subsection addresses

one topic. The results, which are presented in order of frequency, also include a discussion

of subtopics relevant to each overarching theme and illustrative examples of DACOWITS

recommendations related to that topic over time.

vii

The recommendations are presented exactly as originally written (except where redacted for clarity/brevity); as a result,

there are some inconsistencies in capitalization and other aspects of the recommendation text across different years and

iterations of the Committee.

*

23

Figure 4.5. DACOWITS Recommendations by Topic and Decade

Note:

Recommendations that addressed two themes were double-counted in totals.

Size of circles in this gure represents the number of associated recommendations for each decade.

*The year 2020 is included in 2010s

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

87, 88

24

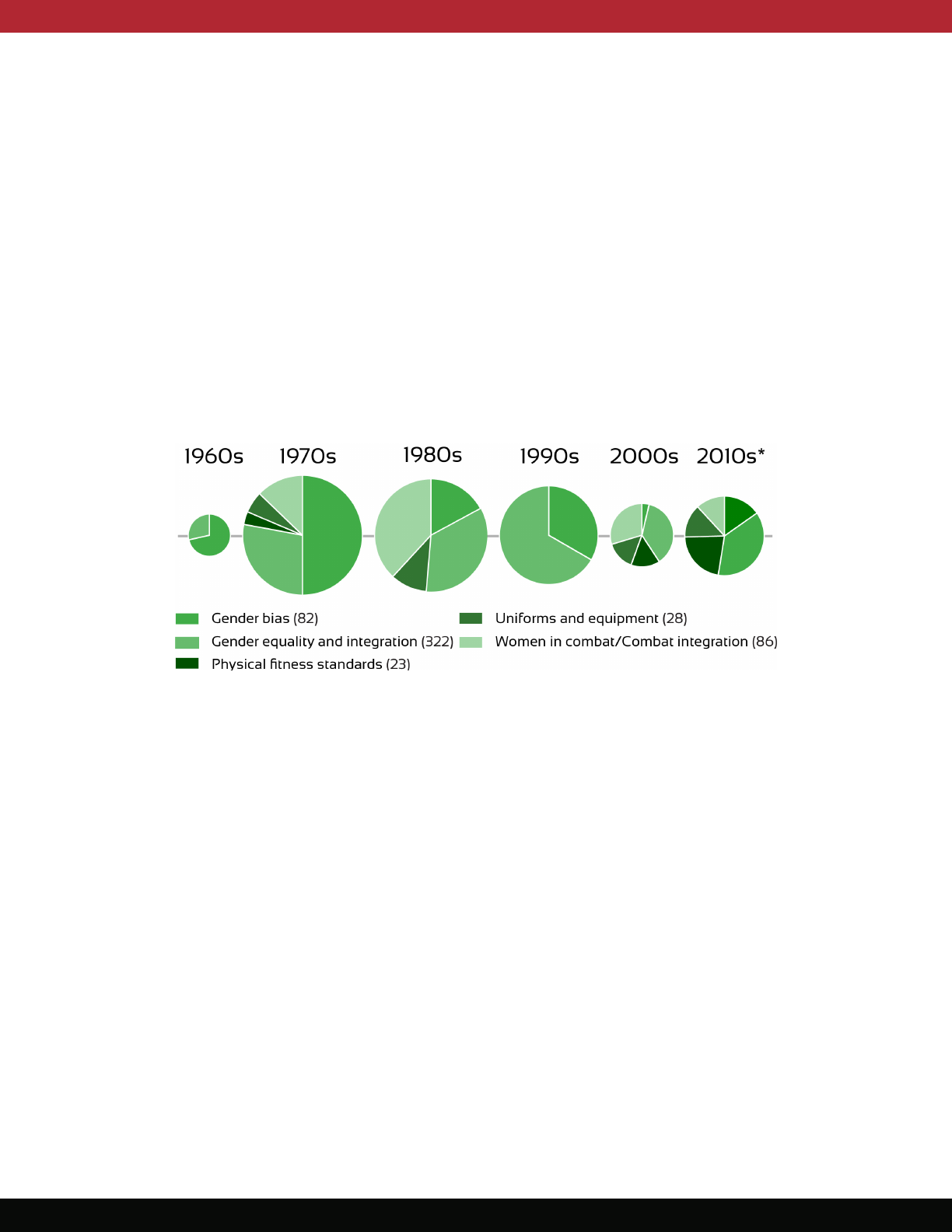

Gender Equality and Integration

Throughout its history a core focus of the Committee has been improving the gender

equality and integration of women into the U.S. military. As a result, the greatest percentage

(24 percent) of all the recommendations made by DACOWITS have focused on gender

equality and integration. Most recently, the Committee recommended in 2020 that “the

Secretary of Defense should designate a single oce of primary responsibility to provide

active attention and oversight to the implementation of the Military Services’ gender

integration plans in order to restore momentum and measure progress.” Within the broader

category of gender equality and integration, DACOWITS has made recommendations

specically related to women in combat, gender bias, uniforms and equipment, and physical

tness standards (see Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6. Proportion of DACOWITS Gender Equality and Integration

Recommendations by Topic and Decade

Note:

Recommendations that addressed two themes were double-counted in totals.

*The year 2020 is included in 2010s.

Sources: DoD, DACOWITS, 1967–2020

89, 90

Women in combat

DACOWITS has been advocating for women’s equal opportunity in combat since 1975

and has made 86 recommendations on this topic. Over the years, the focus of these

recommendations has varied. Between the mid-1970s and early 1990s, DACOWITS

focused on the repeal of or revision to portions of Title 10 of the U.S. Code, which included

combat exclusion statutes that restricted women’s service. Recommendations related

to Title 10 of the U.S. Code, sections 8549 and 6015, represented nearly a quarter (23

percent) of the 86 recommendations DACOWITS made pertaining to women in combat,

including the assignment of women to combat aircraft and on combatant ships. As those

recommendations were implemented and portions of the existing policies were repealed

in 1991 and 1993, respectively, DACOWITS turned its attention to the assignment of women

to Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS) positions in the Army. DACOWITS made 12

recommendations related to opening MLRS positions for women. Recently, DACOWITS

recommended female Service members receive combat training, and DoD remove gender-

based restrictions on military assignments to include career elds, specialties, schooling

25

and training opportunities that were historically closed to women. In December 2015, former

Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter announced all combat jobs would be open to women,

marking a new historic turning point for the U.S. military.

91

DACOWITS has also made many

recommendations related to combat equipment and gear and modications to height and

weight standards to allow women to better serve in these combat roles.

Examples of recommendations related to women in combat included the following:

¡ Allowing women to serve in

combat roles. (1967) “DACOWITS

recommends that laws now

preventing women from serving

their country in combat and

combat related or support

positions be repealed.”

¡ Repealing of portions of Title

10 of the U.S. Code. (1976)

“DACOWITS recommends

that the Oce of the Secretary

of Defense (OSD) direct the

Department of the Navy to initiate legislation to revise or repeal 10 U. S. C. 6015,

so as to provide women of the Navy and Marine Corps access and assignment to

vessels and aircraft under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Navy, and that

OSD direct the Department of the Air Force to initiate amendment or repeal of 10 U.

S. C. 8549, so as to permit assignment of women to aircraft.”

¡ Repealing of portions of Title 10 of the U.S. Code. (1982) “DACOWITS wishes to

reiterate its position urging the Department of Defense and Transportation to seek

repeal of 10 U. S. C. 6015 and 8549. Repeal to these statutes is all the more urgent

now in light of the passage of the Department Ocer Personnel Management Act

(DOPMA), which provides for integrated selection boards for men and women;

however, full equality for women continues to be signicantly inhibited by this

legislation.”

¡ Allowing women to serve in combat roles. (1992) “As the Department of Defense

denes exception to the general policy of opening assignments to women (e.g.,

direct combat on the ground, physical requirements, privacy arrangements),

DACOWITS recommends that great care be taken to ensure no positions or skills

previously or currently open to women be closed.”

¡ Repealing of portions of Title 10 of the U.S. Code. (1992) “DACOWITS recommends

the Secretary of Defense Support the repeal of Tide 10, U. S. C. 6015 (U. S. Navy) and

8549 (U. S. Air Force), the Combat Exclusion Statutes.”

Photo from the DACOWITS archives

26

¡ Opening combat aircraft assignments to women. (1994) “DACOWITS rearms and

further emphasizes its recommendations that the Army, Navy, Marine Corps and Air

Force open all combat aircraft assignments to women, including Army Air Cavalry

Regiments and Special Operations.”

¡ Allowing women to serve in combat roles. (2000) “DACOWITS recommends in

the strongest possible terms that the Army open Multiple Launch Rocket Systems

(MLRS) to the assignment of women....”

¡ Permitting women to receive combat training. (2009) “Considering the uidity

of today’s battleeld, DACOWITS recommends that the Services ensure that all

personnel not possessing a combat arms MOS [military operational specialty]

(i.e., currently all female Service members and many males) receive, at a minimum,

a baseline of combat related training prior to deployment to a combat theatre

of operations. This should include “hands-on” weapons qualication and

familiarization up to and including crew served weapons (e.g., mounted light,

medium, and heavy machine guns), defensive and oensive convoy measures,

perimeter defensive tactics, etc.”

¡ Removing gender-based restrictions on military assignments. (2012) “DoD

should eliminate the 1994 ground combat exclusion policy and direct the Services

to eliminate their respective assignment rules, thereby ending the gender based

restrictions on military assignments. Concurrently, DoD and the Services should

open all related career elds, specialties, schooling and training opportunities that

have been closed to women as a result of the DoD ground combat exclusion policy

and Service assignment policies.”

¡ Opening closed positions to women. (2015) “The Secretary of Defense should open

all closed units, occupational specialties, positions, and training to Service members

who meet the requisite qualications, regardless of gender. No exceptions should

be granted that would continue any restrictions on the service of women.”

viii7

¡ Maximizing opportunities for women to serve on ships. (2019) “The Secretary

of Defense should establish strategic-level oversight within the Navy and Marine

Corps to maximize opportunities for women to serve on ships while meeting

strategic Service needs.”

Gender bias

DACOWITS has a long history of making recommendations aimed at mitigating gender

bias and has made at least 82 recommendations on this topic. In the 1960s and early 1970s,

DACOWITS focused on garnering support for the Griths-Tower Bill, which addressed

unconstitutional inequities in benets for the dependents of military women. In the 1980s,

DACOWITS turned its attention to disparities in Junior Reserve Ocers’ Training Corps

viii

Note this recommendation was sent to the Secretary of Defense early to ensure he considered it before making his

nal decision about opening all units and positions to women.

27

(JROTC), Reserve Ocers’ Training Corps (ROTC), and MSA admission standards for men

and women. While DACOWITS made only one recommendation related to gender bias

between 2000 and 2010, this topic has been of greater focus more recently because

of recommendations made in 2018 and 2019. Since 2012, DACOWITS has made nine

recommendations encouraging the Department and the Military Services to establish,

update, and/or standardize policies that address gender bias or discrimination.

Examples of recommendations related to gender bias included the following:

¡ Supporting the Griths-Tower Bill. (1969) “DACOWITS rearms its stand on H. R.

466, the Griths - Tower bill which provides equal treatment for married women

members of the Armed Services. We welcome with appreciation the armative

support of DoD. DACOWITS stands ready in any and every way to assist in

expediting passage of this bill.”

¡ Removing sex as a determining factor in assignments. (1970) “DACOWITS

notes with concern that the DoD and its civilianization program in support of

the all-volunteer force concept has considered that military positions lled by

Servicewomen are possibly more vulnerable to civilization. The Committee strongly

believes that the sex of the occupant of the position should not be the determining

factor. Should the sex of the occupant be the determining factor, such practice

would be incompatible with the goal of moving toward the zero draft since women

of the Armed Forces represent a source of true volunteers.”

¡ Removing degrading on-base entertainment. (1988)

“DACOWITS recommends that regulations and policies

on clubs and on-base entertainment require that such

entertainment not be degrading to members of either sex.”

¡ Introducing a policy on gender discrimination. (1998)

“DACOWITS recommends that the Secretary of Defense

publish a written policy statement on sexual harassment,

equal opportunity and gender discrimination and emphasize

publicly his commitment to that policy.”

¡ Reviewing policies aimed at eliminating gender

discrimination. (2018) “The Secretary of Defense should

conduct a comprehensive assessment of the eectiveness

of the Military Services’ policies, standards, training, and enforcement to eliminate

gender discrimination and sexual harassment.”

¡ Introducing a policy on gender bias. (2019) “The Secretary of Defense should

establish a DoD policy that denes and provides guidance to eliminate conscious

and unconscious gender bias.”

Photo from the DACOWITS

archives

28

DACOWITS has made 28 recommendations related to uniforms and equipment; the rst

time this recommendation theme appeared in the analysis sample was in 1972. Between

1979 and 1987, the Committee made six recommendations advocating for footwear or boots

designed for the female foot. More recently, DACOWITS has focused its recommendations

on ensuring access to uniforms that are appropriately sized—for example, ensuring combat

uniforms and equipment are designed with female Service members in mind.

Examples of recommendations related to uniforms included the following:

¡ Evaluating adequacy of uniforms and equipment. (1978) “DACOWITS recommends

that the Department of Defense and the Department of Transportation establish a

special inter service committee to evaluate adequacy and make Recommendations

to correct the identied deciencies in the following areas:

a. Field/Organizational Clothing

b. Maintenance allowance for Clothing

c. Special equipment which is indigenous to the unit mission.”

¡ Addressing problems with uniforms. (1982) “DACOWITS considers that the

problems with uniforms, including footwear, for women military members have

continued and been studied long enough. We recommend that the problems of

design, size, quality, distribution, and availability now be appropriately addressed

and promptly resolved. A simpler and better publicized system to register

complaints should be incorporated into the distribution system. DACOWITS

requests a progress report on the resolution of these problems in a brieng at the

FALL 1982 Meeting.”

¡ Designing boots for servicewomen. (1984) “DACOWITS recommends that the

ocers of the Services responsible for uniform initiatives make every, eort to

incorporate state of the art computer technology in the design of uniforms and

equipment for women, for instance, a boot designed to t the female foot.”

¡ Researching equipment designed for servicewomen. (2009) “DACOWITS

recommends that DoD and the Services invest in research and development

of equipment designed specically for use by women. DACOWITS notes that

improved equipment for women can facilitate the success of women in combat,

mission readiness and mission accomplishment. For example, due to the dicult

logistics of urinating while wearing their normally issued clothing and equipment,

particularly in austere environments, women often minimize uid intake, placing

them at risk for dehydration and urinary tract infections.”

¡ Providing gender-appropriate equipment. (2018) “The Secretary of Defense should

require all Military Services, including the Reserve/Guard, to provide servicewomen

with gender appropriate and properly tting personal protective equipment and gear

for both training and operational use.”

Uniforms

29

Physical fitness standards

While DACOWITS made one of its rst recommendations concerning physical tness

standards in 1975, most (55 percent) were made between 2010 and 2019. Initially, these

recommendations focused on developing nondiscriminatory occupational physical

standards and applying the standards equally across Service members and positions. Since

the late 1990s, DACOWITS has focused its recommendations around height, weight, and

body fat measurements, scientically supported and validated standards, and pregnancy

and postpartum standards.