/13,".%3"3& .*5&12*38/13,".%3"3& .*5&12*38

!$)/,"1!$)/,"1

.*5&12*38/./12)&2&2 .*5&12*38/./12/,,&(&

01*.(

".%/13,".%/.$&1.&%$$/4.3".32".%/13,".%/.$&1.&%$$/4.3".32

&120&$3*5&&120&$3*5&

/")/3)

/13,".%3"3& .*5&12*38

/,,/63)*2".%"%%*3*/.",6/1+2"3)33020%72$)/,"1,*#1"180%7&%4)/./123)&2&2

"13/'3)&$$/4.3*.(/--/.2$/./-*$/,*$8/--/.2".%3)&"#/1$/./-*$2/--/.2

&342+./6)/6"$$&223/3)*2%/$4-&.3#&.&:328/4

&$/--&.%&%*3"3*/.&$/--&.%&%*3"3*/.

/3)/")".%/13,".%/.$&1.&%$$/4.3".32&120&$3*5&

.*5&12*38/./12

)&2&2

"0&1

)3302%/*/1()/./12

)*2)&2*2*2#1/4()33/8/4'/1'1&&".%/0&."$$&223)"2#&&."$$&03&%'/1*.$,42*/.*. .*5&12*38/./12

)&2&2#8"."43)/1*9&%"%-*.*231"3/1/'!$)/,"1,&"2&$/.3"$342*'6&$".-"+&3)*2%/$4-&.3-/1&

"$$&22*#,&0%72$)/,"10%7&%4

0

FPDR and Portland:

A Concerned Accountant’s Perspective

by

Noah Roth

An undergraduate honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Bachelor of Science

in

University Honors

and

Accounting

Thesis Adviser

Sarah Engle

Portland State University

2024

Roth 1

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Bob and Bonnie Roth, my grandparents. They always supported and

encouraged me in everything I did. Though they are not here to read this essay, I know that they

would be proud of this work and the long road I have taken to graduate. Academics themselves,

they understood the value of a college education and set me on this path a long time ago, whether

they knew it or not.

I miss and love you both dearly.

Roth 2

Introduction

The Portland Fire and Police Disability and Retirement (FPDR) pension plan is currently

the largest liability on the city of Portland’s books by a factor of six, accounting for more than

half of the total liabilities that the city of Portland is obligated to pay (Portland ACFR, 2023).

The FPDR fund was established in 1942 to provide disability, retirement, and death benefits to

members of the police and fire department and as of the latest financial report, Portlanders are on

the hook for approximately $3.7 billion in pension payments to current and future retirees

(Portland ACFR, 2023, p. 31). The value of this debt obligation does fluctuate based on a few

factors, namely interest and bond rates available to the city, as well as active participants, but has

remained sizable in the recent past and remains distinct from similar pension schemes in other

cities across the United States. This paper aims to thoroughly investigate the current state and

history of the FPDR fund as well as develop recommendations to address the more concerning

elements of the pension plan. The FPDR pension represents a contentious combination of

mismanagement and archaic design, detracting from the wealth of law-abiding citizens in order

to prop up a financial apparatus that is far out of date.

FPDR History and Context

In Portland, like many other cities, it was difficult to attract young men to join the police

and fire departments during and after the Second World War. The city needed to incentivize

young men who either had not gone to war or were looking for employment after their time

serving. To achieve this, members of the city government, in collaboration with Portland Police

and Fire representatives, established the Fire and Police Disability and Retirement pension fund

as a means to encourage new recruits into their programs; however, one of the only avenues of

Roth 3

funding available at the time were additions to property taxes paid in the city of Portland. In

1942, the plan was codified in the city of Portland’s charter by a majority vote, becoming chapter

5 of the city’s charter. This plan levied a new property tax amount based on the real market value

of residential properties in the city, determined by the needs of the fund to cover retirement and

disability benefits to eligible employees. A second group or “part” of the plan was introduced in

the 1980s which tamped down the benefits paid to eligible employees, as it became apparent that

the fund did not need to provide the same level of benefits that it had at its inception.

Later, around the turn of the millennia, there was some more attention paid to the pension

plan in the form of journalists investigating the circumstances of the fund who noticed some

alarming facts about how the pension fund was funded and the people who were receiving those

funds. In 2006, a third tier of the fund was introduced to mitigate the negative attention that the

pension plan received. This final part started to transition new hires to the standard Oregon

Public Employee Retirement System or (O)PERS, with the important distinction being that

employees in this tier would have their contributions to PERS covered by the FPDR pension

fund, rather than relying on their own contributions in the form of payroll deductions. This is

unlike the circumstances for most other public workers in Oregon, as almost all other public

employees are required to contribute pre-tax income to the PERS in order to be adequately

vested, a point of inequity that benefits Portland police officers and firefighters. As of June 30th

2023, the fund is represented by a $3.8 billion liability on the city’s financial statements and a

property tax levy to the tune of $2.73 per $1000 of assessed value or $1.11 per $1000 of real

market value of all property in Portland (FPDR ACFR, 2023, p. 8).

There are predominantly two types of pension plans in the United States: Defined Benefit

(DB) and Defined Contribution (DC). Defined Benefit pension plans offer a guaranteed, fixed

Roth 4

retirement payment paid to employees after they retire, based upon their salary and years of

service. DB plans are common for government employees as it is a primary incentive for

government employers to offset wages that are lower than the private sector for similar positions.

Defined Contribution plans require employees to make either a pre or post income tax

contribution to either a pooled pension fund or individual retirement fund. DC plans are most

commonly offered by private employers, as the onus of retirement payments is primarily on the

employee’s willingness and financial ability to contribute to a pooled or individual retirement

fund, like an IRA or 401(k). Private employers largely shifted from DB to DC plans decades ago,

and they are often not considered a major benefit in the private sector because they do not offer

the same retirement benefits that DB plans have offered to public sector employees. The FPDR

pension plan is a subcategory of a Defined Benefit known as a “pay as you go” plan, meaning

that the needs of the fund are set by its governing body and then met directly by matching

revenues derived from property taxes. The Oregon PERS system is a hybrid plan where

employees are required to make contributions, but benefits are defined at the time of retirement.

PERS also holds about $82 billion in various investments, which netted $2.8 billion in

investment income during the last fiscal year (PERS ACFR, 2023, p. 40-41). The FPDR pension

plan does not hold any interest bearing long term investments, meaning that property owners in

Portland are obligated to pay for all of the fund’s cost: both benefit payments and fund

administrative costs.

Roth 5

FPDR Today:

As of the 2023 ACFR, Portland has two component units within its governmental

accounting structure. The first is Prosper Portland, an entity which is legally separate from the

city but is reported as a discrete component unit in the city’s financial statements. This entity has

most of its financial information presented alongside the citywide financial statements reported

within Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports. Prosper Portland is an agency that was

developed to perform targeted urban renewal projects around the city by offering tax breaks to

small businesses and developing public capital works projects around the city. Prosper Portland

is able to access funding from the city through the issuance of one-day maturity bonds which the

agency redeems immediately; during the 2022-2023 fiscal year, Prosper Portland accessed $54

million through these bonds (Portland ACFR, 2023, p.148). The value of those bonds are

determined by the amount of property taxes that are “sufficient to meet debt service requirements

for outstanding long-term debt and lines of credit” meaning that Prosper Portland is only able to

access excess property taxes after the needs of other long term debt have been met (Portland

ACFR, 2023, pg 148).

The other component unit is the FPDR pension fund, which is considered a blended

entity, meaning that the pension fund’s financial information is not presented alongside the

financial information for the city as a whole, obfuscating the costs associated with the plan if one

only looks at the city’s financial statements. Blended units are generally considered to be so

intertwined with their government body that they are effectively presented as part of the primary

government. In the case of the FPDR pension fund, since it derives all of its revenues from

government activities in the form of property taxes and does not engage in business-like

activities in the same way that Prosper Portland does, it is considered a blended unit and

Roth 6

financial information is not presented alongside the city’s other financial statements, but rather

within the city’s annual financial reports. Blended units are allowed to present their financial

information in this way because they are considered fiscally dependent on the parent entity, in

this case the city itself, and typically require strict oversight from that parent entity. Much of the

pertinent information about the FPDR pension fund is buried within the notes to the Portland

financial statements, and in the Fund’s own annual financial reports.

The FPDR pension fund reported $750,000 in reserve funding, $22 million in cash and

investments, and $5.7 million in property taxes receivable for their fiscal year ended June 30th

2023 (FPDR ACFR, 2023, p. 18). In addition to these reported amounts, the FPDR annual filing

also reports that the fund received $185.2 million in contributions from the property tax levy

determined for the 2022-2023 fiscal year (FPDR ACFR, 2023, p. 10). These values represent a

remarkably well funded pension plan that Portlanders are obligated to pay for, but have no direct

governance or control over. Instead, the FPDR administers the plan itself and is vested with

much of the same fiduciary authority that it was given at its inception in 1942 (Portland ACFR,

2023, p. 175). The FPDR fund is governed by a five member board of trustees. Currently, mayor

Ted Wheeler serves as the Chairperson along with a retired police officer, retired firefighter, and

one civilian. The other civilian trustee spot is vacant. This is one of the primary reasons that the

FPDR pension needs to be altered dramatically: despite drawing all of its revenues from the

Portland property taxes, neither members of the Portland government nor land owning citizens

have any real control or authority over the fund itself; however, amendments to the FPDR

pension plan would be possible with a popular vote from Portlanders, as the city charter can be

altered by a straight vote.

Roth 7

Another source of contention with the FPDR fund is the way in which it calculates

benefits paid out to retired or disabled employees. Employees who are in FPDR tiers 1 and 2, a

little over 2000 retirees, are still paid directly by the fund and do not participate in PERS.

Benefits paid to tier 1 retirees are calculated based on the current pay scale for firefighters and

police officers, which is one reason that the liability has continued to increase rather than

decrease over time. As real wages have increased, so too have benefit payments to over 250

retirees who have not worked for either Portland Fire and Rescue or the Portland Police Bureau

since 1990. Additionally, tier 2 and 3 retirees are allowed to seek other employment and

guaranteed disbursement of at least twenty-five percent of their base pay given to them even if

they are actively employed, despite a retired or disabled designation in the eyes of PFR or PPB.

For these reasons, this liability continues to grow instead of shrink as it is continuously paid from

Portland property taxes annually, and will continue to cover PERS contributions for participating

employees ad infinitum.

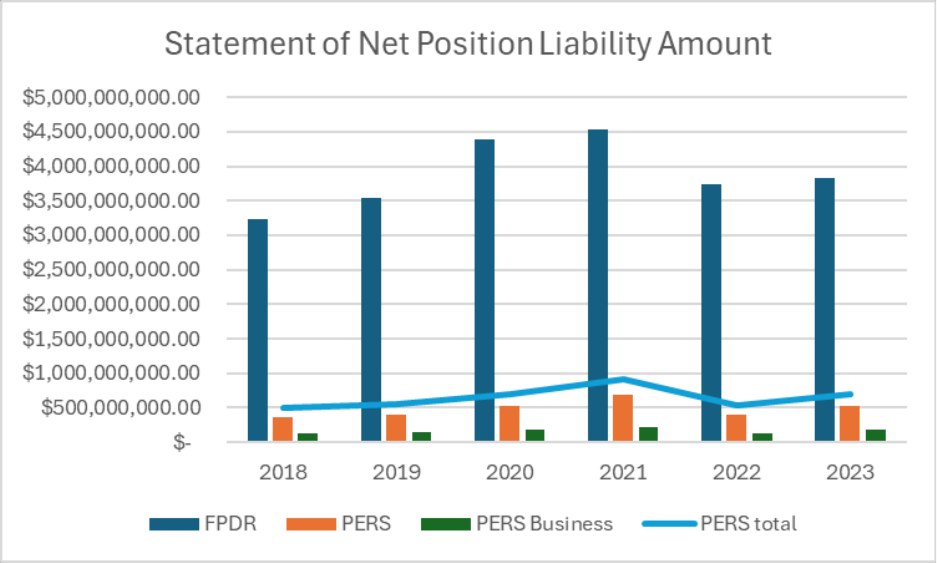

The following chart demonstrates that the fund has, on average, continued to grow over

the past five years, with peaks around a mass-retirement that occurred as a result of serious,

critical attention paid to the police departments nationwide in mid-2020, affecting the 2020 and

2021 enrollment numbers and liability amount. This chart compares the net liability amount

owed by the city to be paid into PERS relative to the FPDR liability. For the former, the city of

Portland is obligated to pay a portion of PERS contributions on behalf of employees active in the

plan. Typically, this liability amount is rolling, meaning that the city makes its contributions to

PERS annually. The liability amounts listed on the statement of net position are the annual

obligations that the city owes to the state-wide program and is relative to number of PERS

eligible employees working for the city of Portland; hence, there is a similar increase in PERS

Roth 8

liabilities around 2020 as eligible employees retired due to the pandemic. The PERS liability is

split between normal government activities and business-like activities, relative to the types of

employees active in PERS.

Chart 1: Comparison of the liability amounts for the FPDR pension fund and the Oregon Public Employee

Retirement System owed by the city of Portland. The latter is divided between normal government activities and

business-like activities, representing contributions on behalf of a multitude of employees to PERS (Portland ACFRs,

2018 - 2023).

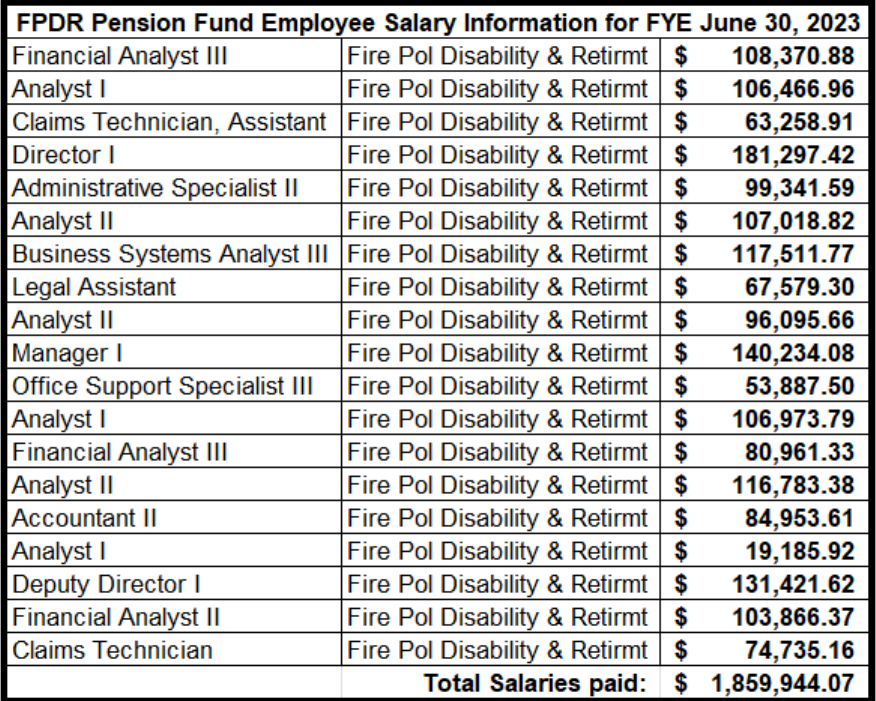

Next, there is the fact that the FPDR pension fund is authorized to pay the wages of 19

full time employees from the general fund of the city of Portland, in addition to leasing an entire

office for these employees to work in. In total, the FPDR fund pays about $1.8 million each year

in wages to a handful of employees who work at their rented office space in downtown Portland.

Below is a table sourced from the City of Portland wage report published for the last fiscal year

detailing the positions and wages paid to employees of the FPDR fund.

Roth 9

Table 1: All of the positions and salaries paid to employees of the FPDR pension fund during the 2022 - 2023 fiscal

year, sourced from the Open Data & Analytics page on portland.gov.

If the FPDR Fund was disbanded, this would free up a number of skilled public

employees to move into other positions more relevant to all Portlanders, not just a small segment

of the public workforce. Additionally, in cutting some of these jobs, the city would free up more

payroll space to hire more staff across other departments within the city of Portland.

The FPDR fund also reports that they entered a noncancelable lease with a third party on

July 1st, 2022 through December 31st, 2027 in the amount of $957,213 paid over the duration of

the lease (FPDR ACFR, 2023, p. 28). The city of Portland owns and operates a multitude of

office buildings throughout the city, so it is curious that the FPDR board of directors elected to

Roth 10

rent from a third party, paying tax dollars to a private LLC, rather than occupy a portion of an

office building owned by the city. It is difficult to determine who exactly owns the building that

the FPDR office is located in, unlike an agency like the Portland Water Bureau, whose offices

are located in a building owned and operated by the city itself, as evidenced by publicly available

property tax records. This rental agreement appears on the surface to be a serious oversight,

intentional or not, by the FPDR board of trustees: why couldn’t they save money by renting an

office already owned by the government which they are a component unit of?

All in all, the FPDR pension fund has a few major issues which this author believes stem

from a lack of community awareness. If the public was made more aware of the circumstances

surrounding the FPDR pension fund, it seems likely that a referendum would be held on the

continued existence of the fund as it is today.

Literature Review:

Over the last twenty years, scholars and economists have performed research on the

efficacy of public pension plans across the United States, with a particular focus on their

resilience, or lack thereof, to economic shifts that impact the broader economic landscape.

Particularly, the Compensation & Benefits Review published by Sage Journals offers bi-monthly

peer reviewed articles addressing trends in employee pay and supplemental benefits for both

private and public positions. Additionally, the Pew Charitable Trusts is a non-profit, non-

governmental organization that was established in 1948 with the purpose of serving and

informing the public on a variety of issues through the use of data analytics. Over the years, Pew

has published several briefs about the status of retirement plans nationwide by offering

comparisons between different states, municipalities, and pension plans.

Roth 11

Bruce Perlman and Christopher Reddick (2022) performed a meta-analysis of 190

government bodies to examine how they were shifting away from Defined Benefit pensions to

alternative funding structures like Direct Contribution or a hybridization of Direct Benefit and

Direct Contribution (DB-DC pensions). Their article cites five factors that inform government

retirement plan reforms: financial constraints, interest group influence, membership

characteristics, liability and state characteristics (Perlman & Reddick, 2022, p. 18). Financial

constraints refers to a government body being unable to adequately fund DB pension plans as

returns on investments or funding sources can fluctuate, while benefits paid to retirees steadily

grows. The authors cite that the shift from a DB plan to a hybrid DC plan in Illinois for public

employees “was instituted primarily as a cost reduction measure” to alleviate the financial

burden placed on the state by providing defined benefits to retirees without contributions from

employees (Perlman & Reddick, 2022, p. 17). Interest group influence is of particular relevance

to the FPDR pension plan as it refers to the “stiff resistance to change from DB pension plans”

by police, fire, and teachers’ groups nationwide despite the financial strain that such plans place

on cities and states (Perlman & Reddick, 2022, p. 19). Membership characteristics refers to

changing demographics across all jobs as younger generations prefer retirement plans that are

more mobile, allowing them to change jobs or careers without jeopardizing their eventual

retirement. The authors cite this as a stark contrast to the attitudes of generations prior, who

would reliably work the same job for their entire career on the expectation of a healthy pension

(Perlman & Reddick, 2022, p. 20). Unfunded current liabilities, like the FPDR liability for the

city of Portland, is another factor these authors considered. Perlman and Reddick suggest that

consistent failure to meet funding requirements associated with DB plans “provide[s] an

environmental incentive for state and local governments to transition from DB pensions to

Roth 12

alternative retirement plans” like DC or DB-DC (Perlman & Reddick, 2022, p. 20). Finally, the

authors considered the characteristics of each state those 190 government bodies reside in.

Specifically, they considered “state unemployment rate, liberal political ideology, union

membership, and plan administ[ration] by the state” as factors that contribute to the shift away

from DB plans to alternatives (Perlman & Reddick, 2022, 21). The authors conclude that it is

crucial for state and local governments to move away from DB plans in favor of alternative plans

more suited to the needs of changing demographics, political pressures, and the economic

landscape, but they do find that their research supported existing research on resistance from

police, fire, and education employees: “interest groups… want to maintain the status quo and

resist change to DB pension plans” (Perlman & Reddick, 2022, p. 26). In Portland, this resistance

comes in the form of unions who would strongly oppose any changes to the FPDR pension plan;

however, the plan could be transitioned by way of amending Chapter 5 of the city charter

through a popular vote.

The Pew Charitable Trusts have published a few articles over the past twenty years

addressing the specific issue of public retirement costs and strategies used nationwide to mitigate

runaway pension funds. One article, titled “A Widening Gap in Cities” addresses an increase in

disparity between the promises made by various state and local governments to provide

retirement benefits and the severe financial strain that bloated or underfunded pension plans can

have on cities nationwide and was published in 2013 with a specific focus on the impact that the

2008/9 recession had on pension plans across the country. This article analyzes financial data

from 2007-2009 to see how well municipalities were able to meet their pension obligations

before, during, and after the recession. Portland is mentioned several times, as the city was only

able to fund about 50% of their pension obligations for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2009.

Roth 13

Presumably, this would have been the result of a significant reduction in property tax revenue in

Portland as a result of the nationwide economic shift. While the article does not specifically call

out the FPDR pension fund, the Pew Charitable Trusts report that Portland had a pension liability

of approximately $2.7 billion in 2009. This figure is consistent with the present liability amount

for the FPDR pension, today.

A second article by the Pew Charitable Trusts titled “Basic Legal Protections Vary

Widely for Participants in Public Retirement Plans” focuses on the fiduciary responsibilities

entrusted to the custodians of public retirement plans. “Fiduciaries” refers to the trustees and

administrators who have the authority to manage the assets which a pension fund holds, usually

by investing and allocating those assets to grow the fund. This article examines the laws

surrounding fiduciaries across the United States and offers a few short case studies into specific

pension plans. For example, Pew cites “weak governance practices” as key factor in the “serious

fiscal distress facing the Dallas Police and Fire Pension System” owed mostly to a lackluster real

estate market that subsequently resulted in “$1.4 billion in unfunded liabilities” which will

inevitably cost taxpayers millions of dollars annually to repay (Pew, 2017). The article goes on

to define eight key fiduciary duties as defined by the Uniform Management of Public Employee

Retirement Systems Act of 1997, of which Oregon has codified seven within state law. Two of

the codified fiduciary duties are of particular interest: incurring costs that are appropriate and

reasonable and the responsibility to diversify investment in order to grow their respective

pension plan. As previously mentioned, the FPDR pension fund has entered into an expensive

long-term lease which is arguably unnecessary for the facilitation of its retirement system given

the volume of properties available to Portland government agencies. Additionally, due to its

Roth 14

status as a Defined Benefit, “pay as you go” pension plan, the fiduciaries of the FPDR pension

are under no real obligation to diversify investments or grow their assets.

Robert Lee and Joseph Vonasek collaborated on two papers examining the status of fire

and police pensions in the state of Florida; their first article in 2011 presents some history and

context for plans in Florida that resemble the FPDR pension fund in Portland.The second article,

published in 2021, re-examines those same plans and considers how they changed over that ten

year period. The retirement funds that these authors investigated are considered Defined Benefits

plans, like the FPDR pension, but do make long term stock investments to help maintain

adequate funding, unlike the “pay as you go” structure of the FPDR pension. In addition, these

plans are “siloed,” meaning that each municipality is responsible for maintaining its own fund

without additional monies from the state or county. Lee and Vonasek found that the vast majority

of pension funds would result in funding shortfalls unless statutes of Florida laws were changed

to require participants to contribute to their pension fund, creating a hybrid DB-DC program that

is less dependent on fickle revenues. The primary concern for these authors was a marked

decrease in pension plan funding due to the structure of Florida’s pension apparatus for

firefighters and police. Funding for these plans was derived from “premium tax revenue” on

property and casualty insurance policies written within a given municipality (Lee & Vonasek,

2011, p. 166). Effectively, these premium taxes would grow as the populations and prices of

insurance policies increased across the state of Florida; however, Lee and Vonasek examined the

economic recession of 2008/9 in the context of these revenues. That fiscal year saw a significant

decrease in premium tax revenues to fund fire and police pensions, resulting in many

underfunded pension plans across the state (Lee & Vonasek, 2011, p. 168). The authors drew the

Roth 15

conclusion that tying pension funding to revenues susceptible to market shifts “may be

contributing to a financially unsustainable system” (Lee & Vonasek, 2011, p. 168).

In 2021, Robert Lee and Joseph Vonasek re-examined the same municipalities they had

initially investigated in 2011. This study yielded similar results, many of the same plans that had

been underfunded in 2009 were still underfunded ten years later. The authors do note, however,

that they expected the plans to be better funded because many of them were directly invested in

the Stock Market as a means of generating interest on the premium tax revenues that they were

allowed to collect within their given municipalities, a Stock Market that saw tremendous growth

from 2016 - 2019 (Vonasek & Lee, 2021, p. 161). Again, the FPDR pension fund does not

actively invest in the same way. Instead, it is considered a “pay as you go” pension fund which

only holds cash and short term investments meaning that it does not invest in stock the same way

that PERS maintains a robust portfolio (Milliman Actuarial Report on FPDR, 2022, p. 9). Lee

and Vonasek recommend that the Florida municipal pension funds for firefighters and police

officers transition from Defined Benefits to Defined Contribution as a means to mitigate the

chronic underfunding of those targeted pension plans, by way of drawing revenue from

employee contributions and aligning the siloed retirement funds with the Florida state retirement

system (Vonasek & Lee, 2021, p. 172). A similar change is necessary to address the financial

burden that the FPDR pension places on the city of Portland.

Roth 16

Pension Plans Across the United States:

Nationwide, Defined Benefit “pay as you go” pension plans like the FPDR have largely

been done away with, due to social and political pressures, to create more equity for public

employees. The Oregon PERS is a good example of a state-wide hybrid DB-DC program that

offers retirement funding to all public employees, regardless of their specific jobs or roles in the

public sector. Even though PERS is a pooled public pension fund, employees are still required to

contribute a portion of their salary during their time as a teacher or other public employee. That

is not currently the case with the FPDR pension. As previously discussed, members of FPDR

part 3, the latest iteration of the pension plan, are not obligated to pay into PERS as their

contributions are covered by taxes paid by property owners in Portland.

Colorado has established a state-wide program to fund retirement and disability benefits

for fire and police employees handled by the Fire and Police Pension Association of Colorado, or

FPPA. FPPA still pays out a Defined Benefit pension to many former employees, but has

recently started to require employee contributions in addition to revenues collected from

participating municipalities. Similar to the FPDR pension, FPPA pays out a Defined Benefit

pension to employees hired before January 1st 2004, employees hired after that date and enrolled

in a statewide hybrid DB-DC plan that is more similar to Oregon’s PERS (FPPA ACFR, 2023, p.

31). Each participating Colorado municipality is obligated to contribute a proportion of payroll

expenses paid to FPPA participants, and those participants are required to contribute a portion of

their wages to the fund directly. For example, for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2023, the

city of Denver contributed $22 million to FPPA which was 8.9% of payroll expenses paid to

Roth 17

firefighters and police officers in the city during that fiscal year (Denver ACFR, 2023, p. 146).

During the same financial period, FPPA reported a total of $151 million in employer

contributions, funding coming from Denver and other municipalities, as well as $174 million in

contributions from participants (FPPA ACFR, 2023, p. 25). By collecting from both

municipalities and participants, the FPPA is able to secure a consistent stream of new additions

without directly burdening any specific municipality or levying additional taxes from non-

participant citizens throughout the state. In this way, there is much more equity for Colorado

taxpayers as well as government employees who participate in FPPA as neither party is obligated

to finance the entirety of the pension fund but rather, the burden of financing is shared

proportionately by cities and participating employees. Additionally, this allows FPPA access to a

much larger pool of financial resources to invest, manage, and distribute to retirees.

Overall, FPPA represents a program that has started the arduous process of transitioning

away from Defined Benefit plans and towards a more equitable solution for all parties; however,

as highlighted in Perlman and Reddick, there is a lack of mobility for current employees who are

participating in FPPA. Because their retirement is tied to a statewide, targeted pension plan,

active employees are unable to transfer their retirement into other public pension plans like

Colorado’s PARA, a program similar to Oregon’s PERS, or move across state lines, even if they

continue to work in the public sector. For this reason, FPPA is not a perfect system nor does it

provide a level of equity for employees, but it does represent a willingness to adapt antiquated

pension plans to the modern era.

On the opposite extreme is the case of the city of Central Falls, Rhode Island. On August

1st, 2011, one of the smallest cities in the smallest state declared Chapter 9 bankruptcy, owed in

large part to a $80 million liability payable to fire and police retirees who had left their positions

Roth 18

years prior. Zachary Malinowski provided commentary on the case in the Chicago Planning

journal in 2013. His research found that more that 55% of retirees were collecting disability

payments from the city and that between 1978 and 1988, “82 percent of the public safety

workers left with injuries they claimed they suffered while on duty” and that the average age at

retirement was 46, meaning that Central Falls was “burdened with millions of dollars in

payments for decades to come” (Malinowski 2013). At the time, Central Falls had a population

of just under 20,000 meaning that it was relatively easy to trace retirees and their benefit

payments, the same cannot be said for the city of Portland, populated by over half a million. It is

highly likely that if such an analysis was conducted in Portland, it would uncover similar results

in terms of retirement payments being made to individuals far younger than the typical retiree.

Therein lies one of the biggest financial issues with the FPDR pension fund: a high quantity of

young retirees vested in an archaic Defined Benefit plan have caused the pension liability to

continually increase as those retirees continue to collect benefits for decades without any

mechanism to reduce or offset the liability. That is not to say that Portland will face the same fate

as Central Falls, but a liability as colossal as that owed by Portland to the FPDR pension fund is

cause for great concern.

Recommendations:

Reform is necessary to mitigate the financial burden which the FPDR pension fund

places not only on the city of Portland, but more importantly the burden it puts on property

owning Portlanders. As of the 2023 tax year, property taxes paid to the FPDR pension fund

accounted for approximately 10% of the average Portland property tax bill: for a home with a

real market value of $500,000 about $600 of a $7000 tax bill would go directly to the FPDR

Roth 19

pension fund. This amount is roughly equivalent to the amount paid to the Portland Public

Schools bond, which is a measure voted on regularly by Portland citizens. Arguably, the best

solution would be to eliminate the FPDR pension fund and Chapter 5 of the city charter

altogether. Retirees in parts 1 and 2 of the FPDR pension could be rolled into the Oregon Public

Employee Retirement System to the relevant tiers and plans they would have been allowed to

participate in had their years of service been in a position with PERS. Newer hires would not

have their current retirement system affected that much; however, it would be necessary to

require new hires to contribute to PERS out of their own paycheck rather than rely on Portland

property taxes to pay it for them. Adding some 2000 participants would put some financial stress

on PERS, but this strain could be mitigated by rolling over all existing FPDR funds and

investments into the state program which could help offset the logistical complexity of enrolling

these retirees retroactively. Additionally, several skilled members of the FPDR staff would be

valuable in handling this transition, ensuring that their employment would not be stopped due to

the elimination of the FPDR fund. In eliminating the fund altogether, PFR and PPB employees

would then be obligated to pay into PERS at the same rate that most other public employees in

the state are, and PERS is already set up to provide preferential treatment to firefighters and

police officers, with a lower retirement age and generally better pension rates.

Ideally, these changes would incentivize the Portland Police Bureau to work to keep the

city safe but it is highly likely that there would be significant pushback from their employees and

union. A safer city would eventually translate to more public sector jobs, higher revenues for the

city, and would help to rebuild trust in PPB, specifically. Other incentives, perhaps a stipend for

continuing education, may be necessary to ensure the continued cooperation of the PPB. A

benefit for PFR and PPB employees would be that there would be some more flexibility for them

Roth 20

if they decided to seek other employment as civil servants. For example, if a firefighter wanted to

change careers and work at the city parks department, there would not be any disruptions to their

retirement accruals, they would continue to pay a similar amount into PERS and may have the

opportunity to earn a higher salary, resulting in a better pension than if they were to continue

working for Portland Fire and Rescue.

Regardless of what the changes are, the only way for reforms to be made is a ballot

measure passed by Portlanders to address this issue that has plagued the financial situation of this

city for over eighty years. It should be possible to find a solution that creates more equity for all

public employees while lowering the tax burden for land owning Portlanders. Of course, there is

the possibility that the unions for Portland Fire and Rescue and the Portland Police Bureau could

sue to block such changes, which could delay the process significantly. Ultimately, it would

likely be in the hands of higher courts to determine if the people of Portland have the right to

make changes to the FPDR pension fund.

Conclusion

Portlanders do not have any direct input on the FPDR pension liability, since it was built

into the City Charter and it is not a regular ballot measure, like bond measures for schools and

additional tax levies road maintenance tend to be. Already, the FPDR pension fund has

continually grown to account for more than half of the total liabilities owed by the city of

Portland and will continue to grow unless changes are made. Furthermore, research shows that

there is a significant risk to the city’s financial future if this liability is allowed to grow

perpetually, as the case of Central Falls demonstrates. As it stands, Portlanders will be obligated

to pay into this fund for decades to come. The time to rectify this situation was decades ago, but

Roth 21

dramatically altering the FPDR pension fund is a change that could be made in the next few

years with enough support from Portland voters.

To do so would require a great deal of work on the part of responsible civil servants: an

audit of all 2000 or so recipients to determine those who are eligible to receive retirement

benefits per the rules of the Oregon PERS and drastically reduce benefits paid to members of

FPDR Parts 1 and 2, especially for retirees who have worked after “retirement” from the

Portland Fire Department or Police Bureau. Finally, the remaining assets in the trust of the FPDR

could be rolled into PERS and the committee and administrative apparatus for overseeing the

fund could then be dissolved, saving the city of Portland from paying for an entity it does not

need. All in all, this liability oversight represents what seems to be a common problem in the city

of Portland: an antiquated solution to a decades old problem demonstrates that this city claims to

place value in one place while completely neglecting a reconciliation with its history that could

culminate in benefits for generations to come. More equity for public workers would build trust

among agencies and government bodies that operate within the city, and while it is difficult to

prescribe a dismantling of such a program, it is necessary to move the city forward.

Roth 22

Bibliography

City and County of Denver, Colorado. (2023), Annual Comprehensive Financial Report: Year

Ended December 31, 2022. https://denvergov.org/Government/Agencies-Departments-

Offices/Agencies-Departments-Offices-Directory/Department-of-Finance/Financial-

Reports/Annual-Comprehensive-Financial-Report

City of Portland, Oregon. (2018). Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the year ended

June 30 2018. https://www.portland.gov/omf/brfs/accounting/finance-reports

City of Portland, Oregon. (2019). Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the year ended

June 30 2019. https://www.portland.gov/omf/brfs/accounting/finance-reports

City of Portland, Oregon. (2020). Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the year ended

June 30 2020. https://www.portland.gov/omf/brfs/accounting/finance-reports

City of Portland, Oregon. (2021). Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the year ended

June 30 2021. https://www.portland.gov/omf/brfs/accounting/finance-reports

City of Portland, Oregon. (2022). Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the year ended

June 30 2022. https://www.portland.gov/omf/brfs/accounting/finance-reports

City of Portland, Oregon. (2023). Annual Comprehensive Financial Report for the year ended

June 30 2023. https://www.portland.gov/omf/brfs/accounting/finance-reports

FPDR Pension Fund (2023). Report of the Independent Auditors and Financial Statements For

the fiscal year ended June 30, 2023. https://www.portland.gov/fpdr/budget-reports

Lee, R. E., & Vonasek, J., PhD. (2011). Police and Fire Pensions in Florida: A Historical

Perspective and Cause for Future Concerns. Compensation and Benefits Review, 43(3),

164. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886368711403684

Malinowski, W. Z. (2013). PENSION POSTER CHILD. Planning, 79(3), 23-27.

https://stats.lib.pdx.edu/proxy.php?url=https://www.proquest.com/trade-journals/pension-

poster-child/docview/1326322507/se-2

Milliman Incorporated (2023). CITY OF PORTLAND FIRE & POLICE DISABILITY &

RETIREMENT (FPDR) FUND Pension Actuarial Valuation Report as of June 30, 2022.

https://www.portland.gov/fpdr/budget-reports

Roth 23

Perlman, B. J., & Reddick, C. G. (2022). From Stand-Alone Pensions to Alternative Retirement

Plans: Examining State and Local Governments. Compensation and Benefits Review,

54(1), 12-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/08863687211030795

Pew Charitable Trusts (2017). Basic Legal Protections Vary Widely for Participants in Public

Retirement Plans. Report, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-

briefs/2017/11/basic-legal-protections-vary-widely-for-participants-in-public-retirement-

plans.

Pew Charitable Trusts (2013). A Widening Gap in Cities: Shortfalls in funding for pensions and

retiree health care. Report, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-

/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/pcs_assets/2013/pewcitypensionsreportpdf.pdf

Vonasek, J., & Lee, R. (2021). Police and Fire Pensions in Florida: A Comparison of

Conditions After 10 Years. Compensation and Benefits Review, 53(4), 159-174.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0886368721999137