101st Annual Report

2014

B O A R D O F G O V E R N O R S O F T H E F E D E R A L R E S E R V E S Y S T E M

101st Annual Report

2014

B O A R D O F G O V E R N O R S O F T H E F E D E R A L R E S E R V E S Y S T E M

This and other Federal Reserve Board reports and publications are available online at

www.federalreserve.gov/publications/default.htm.

To order copies of Federal Reserve Board publications offered in print,

see the Board’s Publication Order Form (

www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/orderform.pdf)

or contact:

Publications Fulfillment

Mail

Stop N-127

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Washington, DC 20551

(ph) 202-452-3245

(fax) 202-728-5886

(e-mail) [email protected]

Letter of Transmittal

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Washington, D.C.

June 2015

The Speaker of the House of Representatives:

Pursuant to the requirements of section 10 of the Federal Reserve Act, I am pleased to submit the 101st annual

report of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

This report covers operations of the Board during calendar year 2014.

Sincerely,

Janet L. Yellen

Chair

Overview

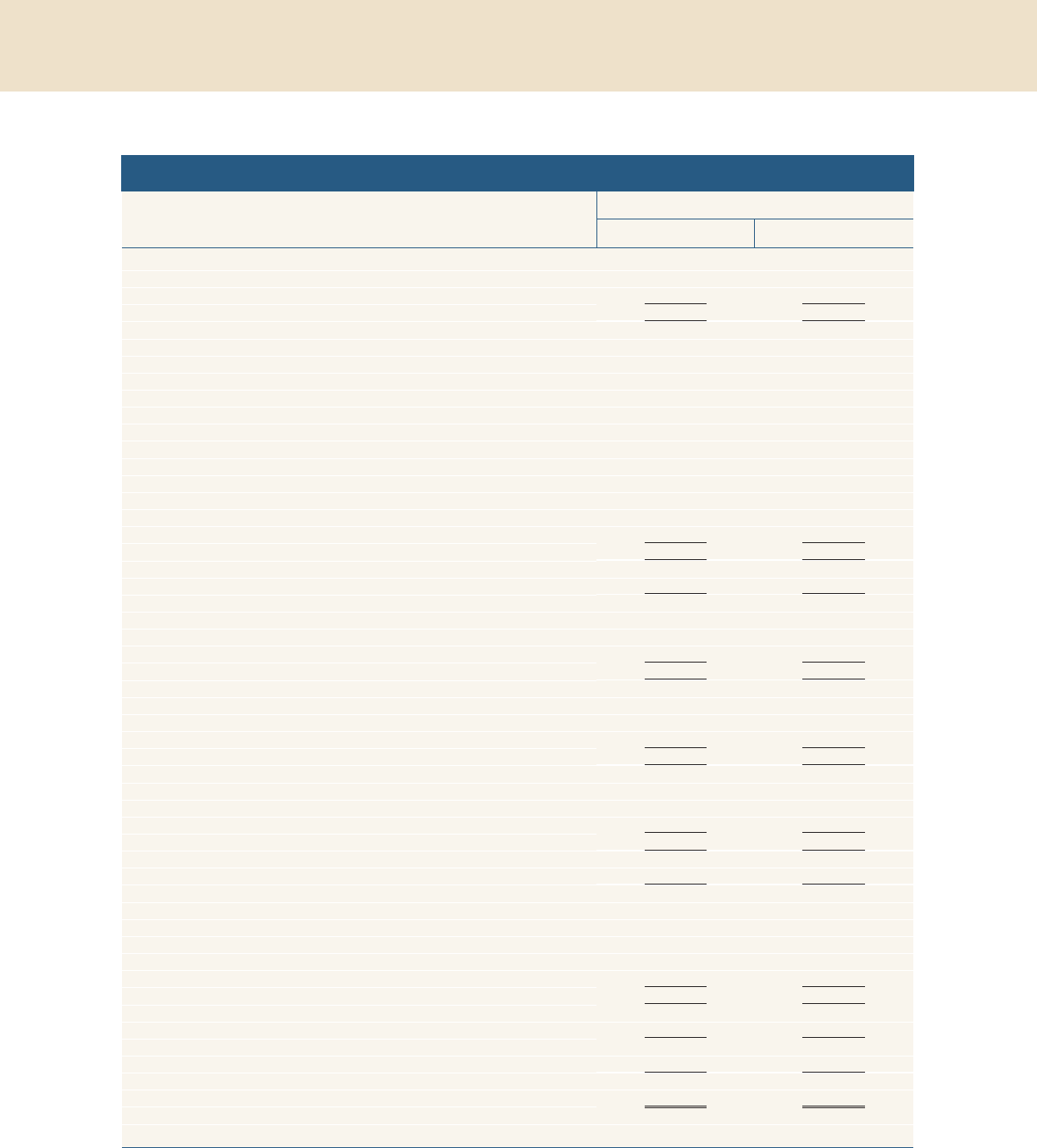

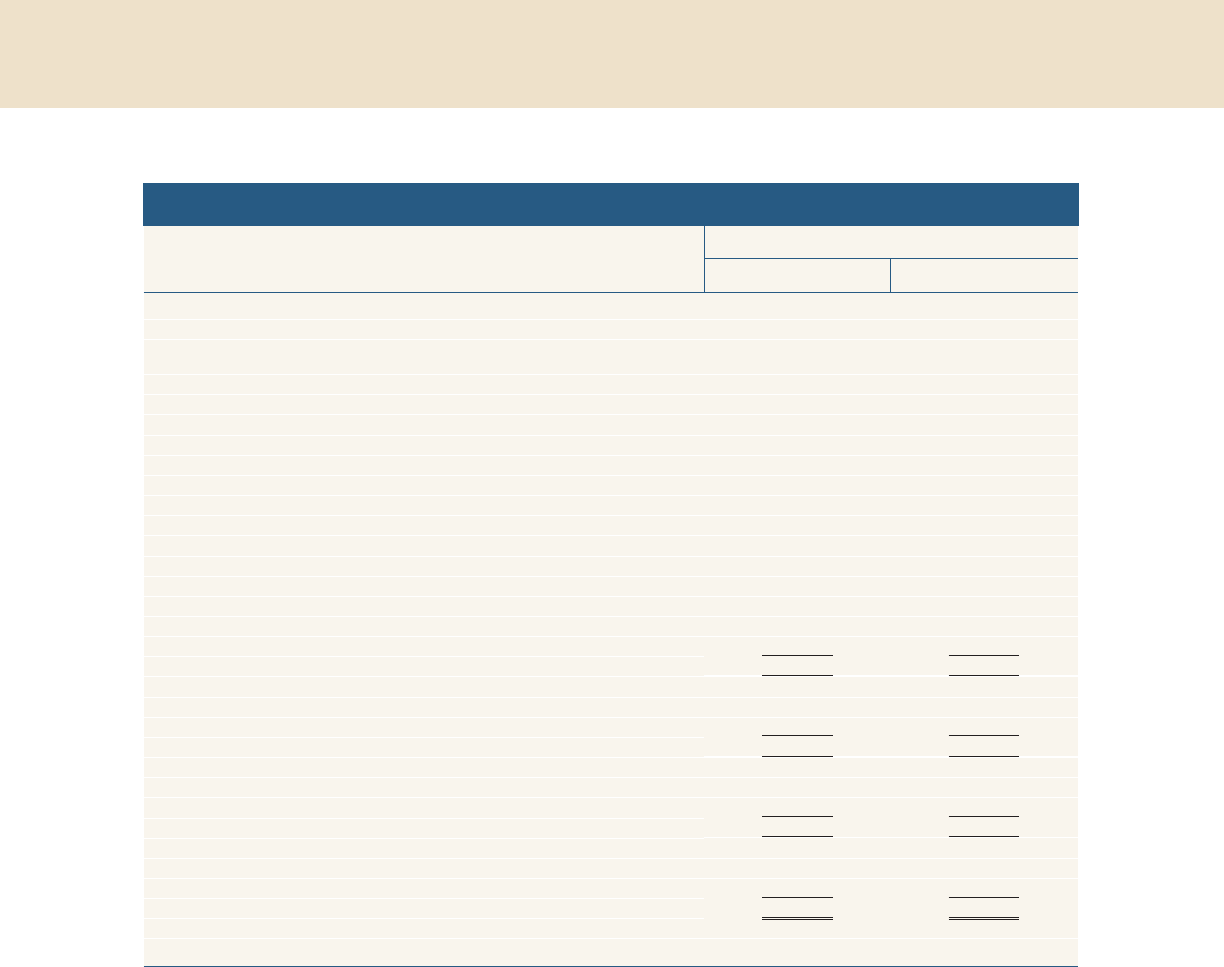

............. .............. .............. .............. . .............. .............. .............. ........................... ........ 1

About This Report ........ . .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ............ 1

About the Federal Reserve System ............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ........... 2

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments

............. .............. .............. .............. . .... 5

Monetary Policy Report of February 2015 .................... .............. .............. .............. .............. ........ 5

Monetary Policy Report of July 2014 ............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ....... 22

Financial Stability

............. .............. .............. .............. . .............. .............. ........................... ... 37

Monitoring Risks to Financial Stability .................... .............. .............. ........................... ............. 38

Macroprudential Supervision of Large, Complex Financial Institutions ........ .............. .............. ..... 43

Domestic and International Cooperation and Coordination ........ .............. .............. .............. ........ 44

Supervision and Regulation

............. .............. .............. .............. . ........................... ............. 47

2014 Developments .................................. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .......... 47

Supervision ................ .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ............ 49

Regulation ............... .............. . .............. ........................... .............. .............. .............. .............. . 71

Consumer and Community Affairs

............. .............. .............. .............. . .............. ........... 75

Supervision and Examinations .................. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ........... 75

Consumer Laws and Regulations ............................. .............. .............. .............. .............. .......... 86

Consumer Research and Emerging-Issues and Policy Analysis ......... .............. .............. .............. 88

Community Development ............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ......... 91

Federal Reserve Banks

............. .............. .............. .............. . .............. ........................... ......... 95

Federal Reserve Priced Services ............................. .............. .............. .............. .............. ........... 95

Currency and Coin .................... . .............. .............. ........................... .............. .............. ............ 98

Fiscal Agency and Government Depository Services ........... .............. .............. .............. .............. 99

Use of Federal Reserve Intraday Credit ............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. . 102

FedLine Access to Reserve Bank Services ..... .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .... 102

Information Technology ................... .............. .............. ........................... .............. .............. ..... 103

Examinations of the Federal Reserve Banks ........................ .............. .............. .............. ........... 103

Income and Expenses .................. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ....... 104

SOMA Holdings and Loans ............................. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ... 105

Federal Reserve Bank Premises ........................ .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. . 108

Pro Forma Financial Statements for Federal Reserve Priced Services ............. .............. ........... 109

v

Contents

Other Federal Reserve Operations

............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ............. 115

Regulatory Developments: Dodd-Frank Act Implementation ....................................... .............. . 115

The Board of Governors and the Government Performance and Results Act ............... . .............. 119

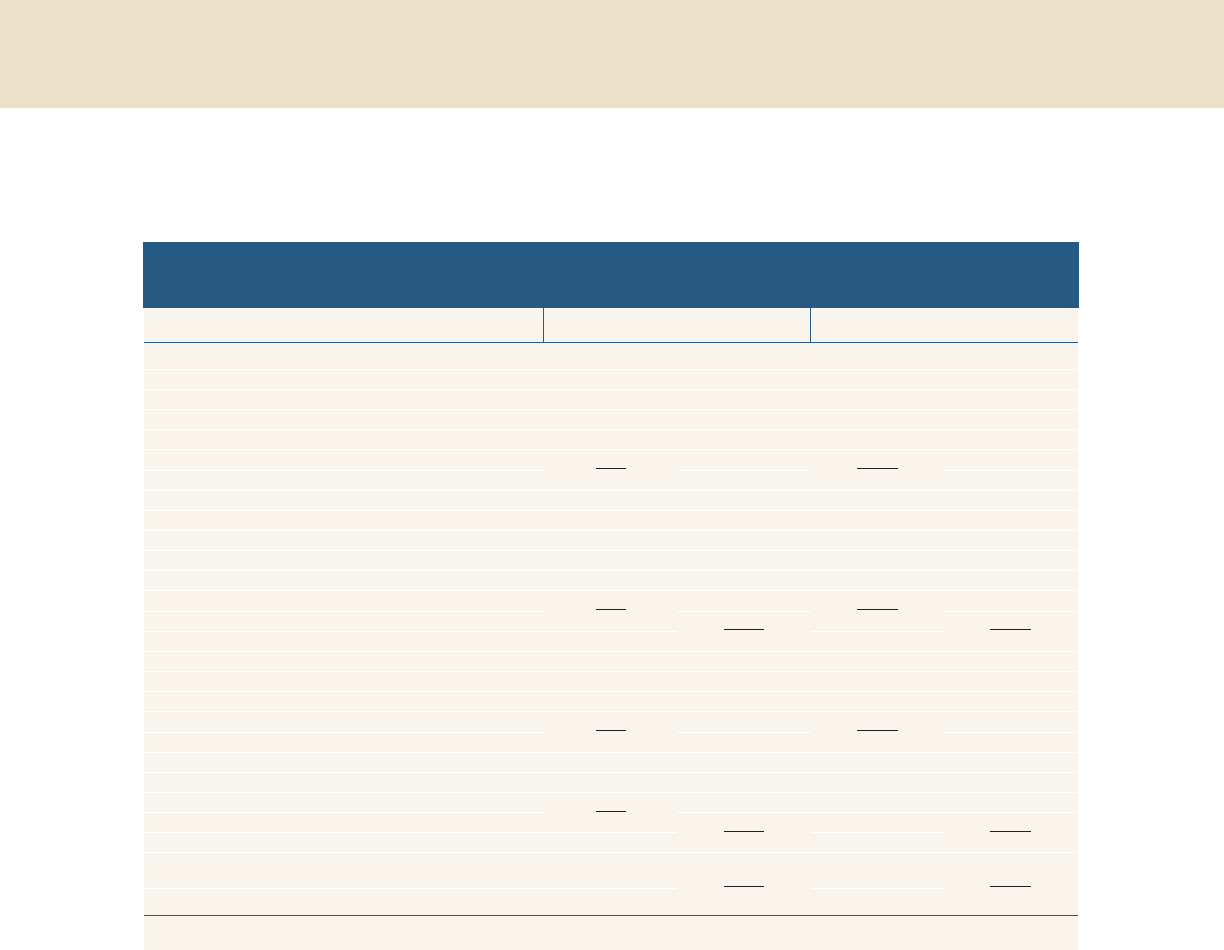

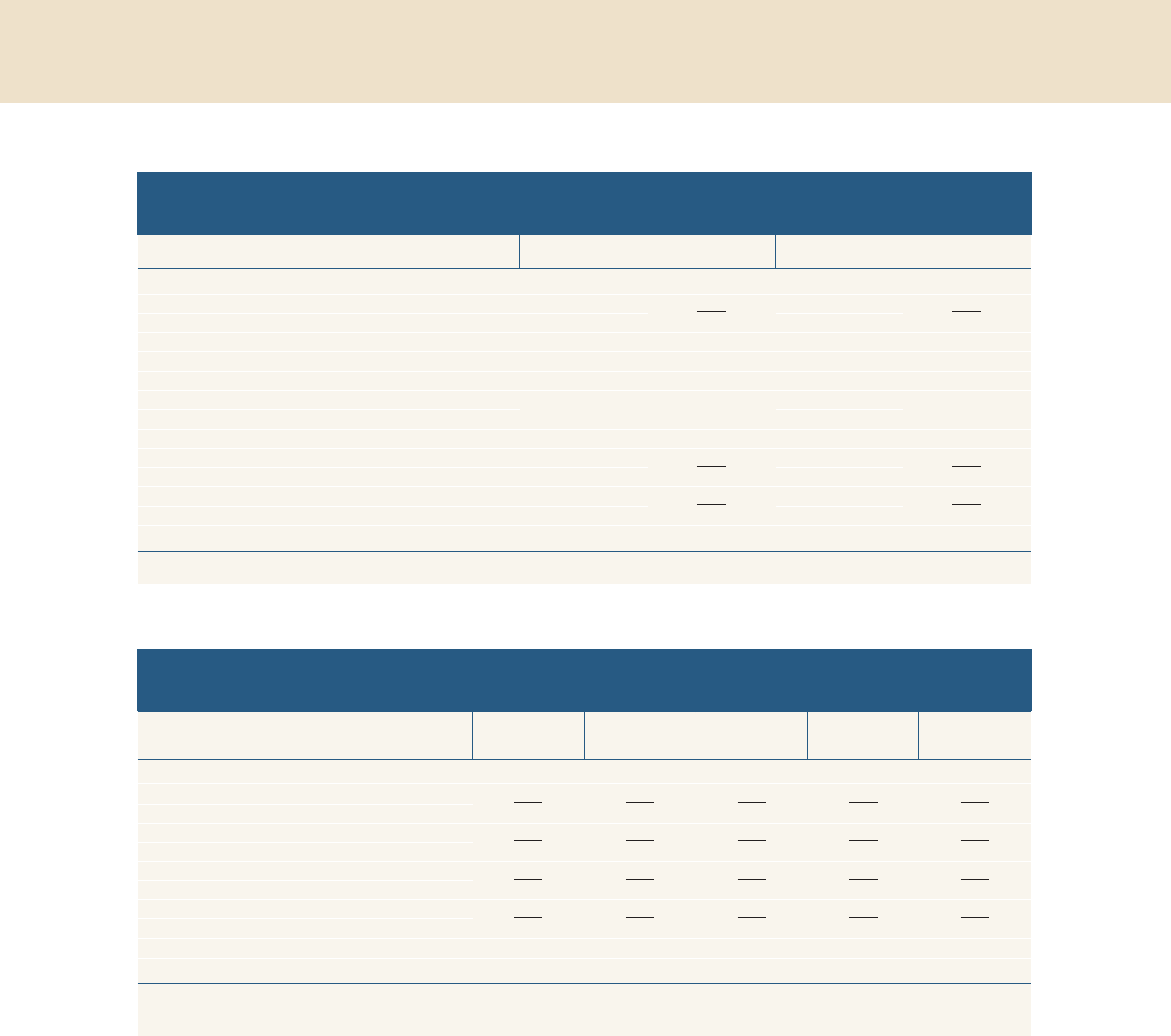

Record of Policy Actions of the Board of Governors

............. .............. .............. .... 121

Rules and Regulations ................ .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ......... 121

Policy Statements and Other Actions ................... .............. .............. .............. .............. ............ 125

Discount Rates for Depository Institutions in 2014 ............ .............. .............. .............. .............. 126

Minutes of Federal Open Market Committee Meetings

............. .............. .............. 129

Meeting Held on January 28–29, 2014 ... . .............. .............. .............. ........................... ............. 130

Meeting Held on March 18–19, 2014 ............ .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ...... 149

Meeting Held on April 29–30, 2014 ........ .............. .............. .............. ........................... .............. 174

Meeting Held on June 17–18, 2014 ..................... .............. .............. .............. .............. ............. 184

Meeting Held on July 29–30, 2014 ........... .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .......... 210

Meeting Held on September 16–17, 2014 ................. .............. .............. .............. .............. ........ 222

Meeting Held on October 28–29, 2014 ................... . .............. .............. ........................... .......... 248

Meeting Held on December 16–17, 2014 ........................ . .............. .............. .............. .............. . 261

Litigation

............. .............. .............. ...........

............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ........ 285

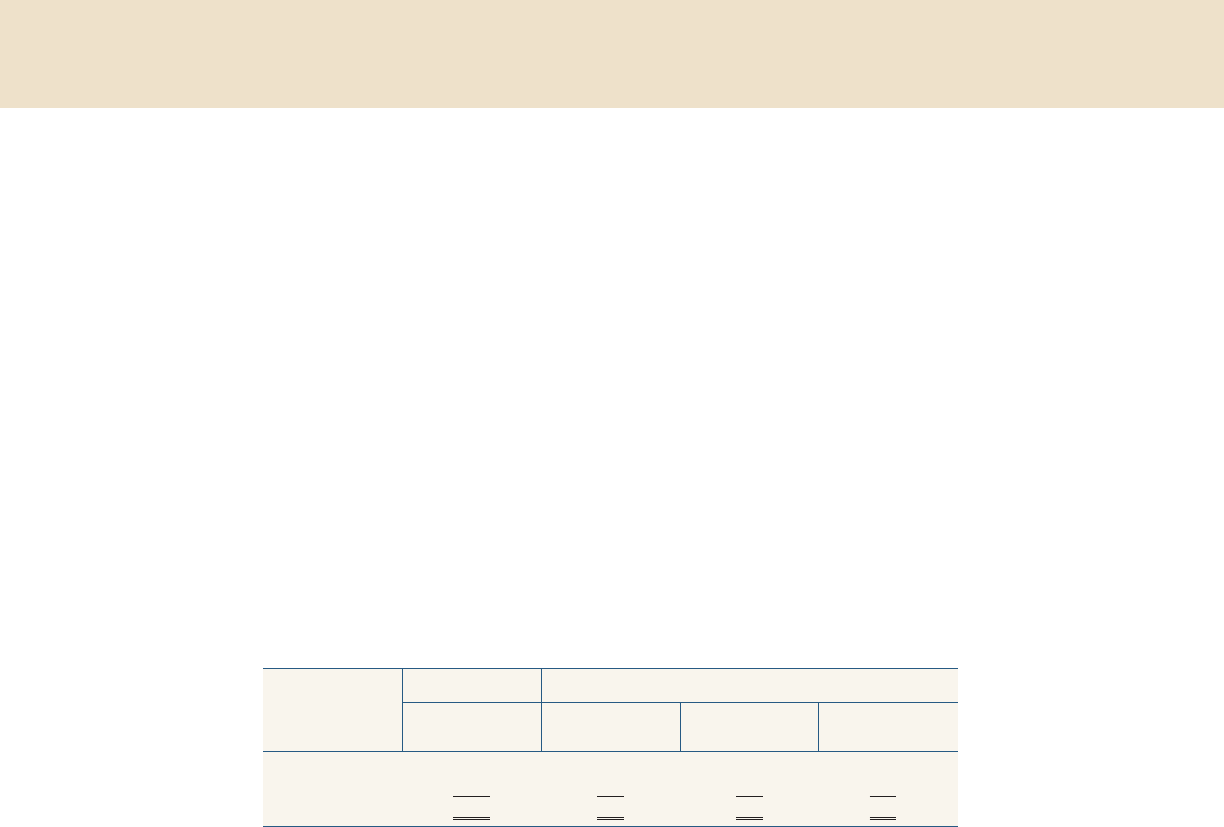

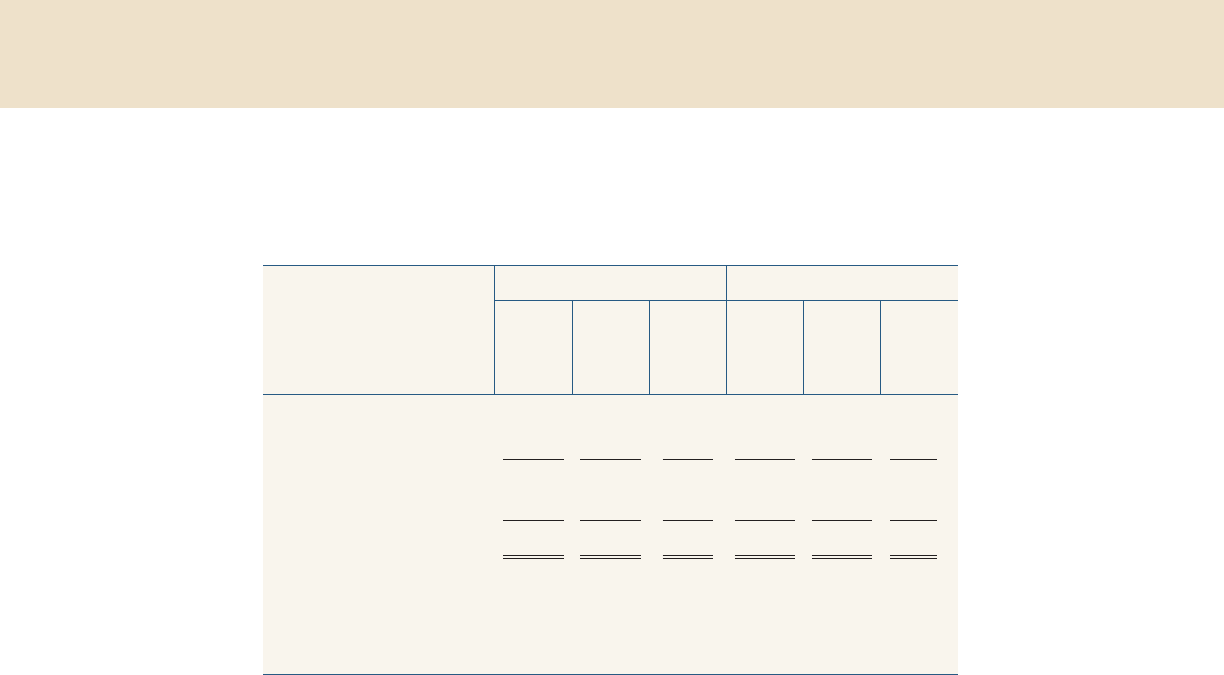

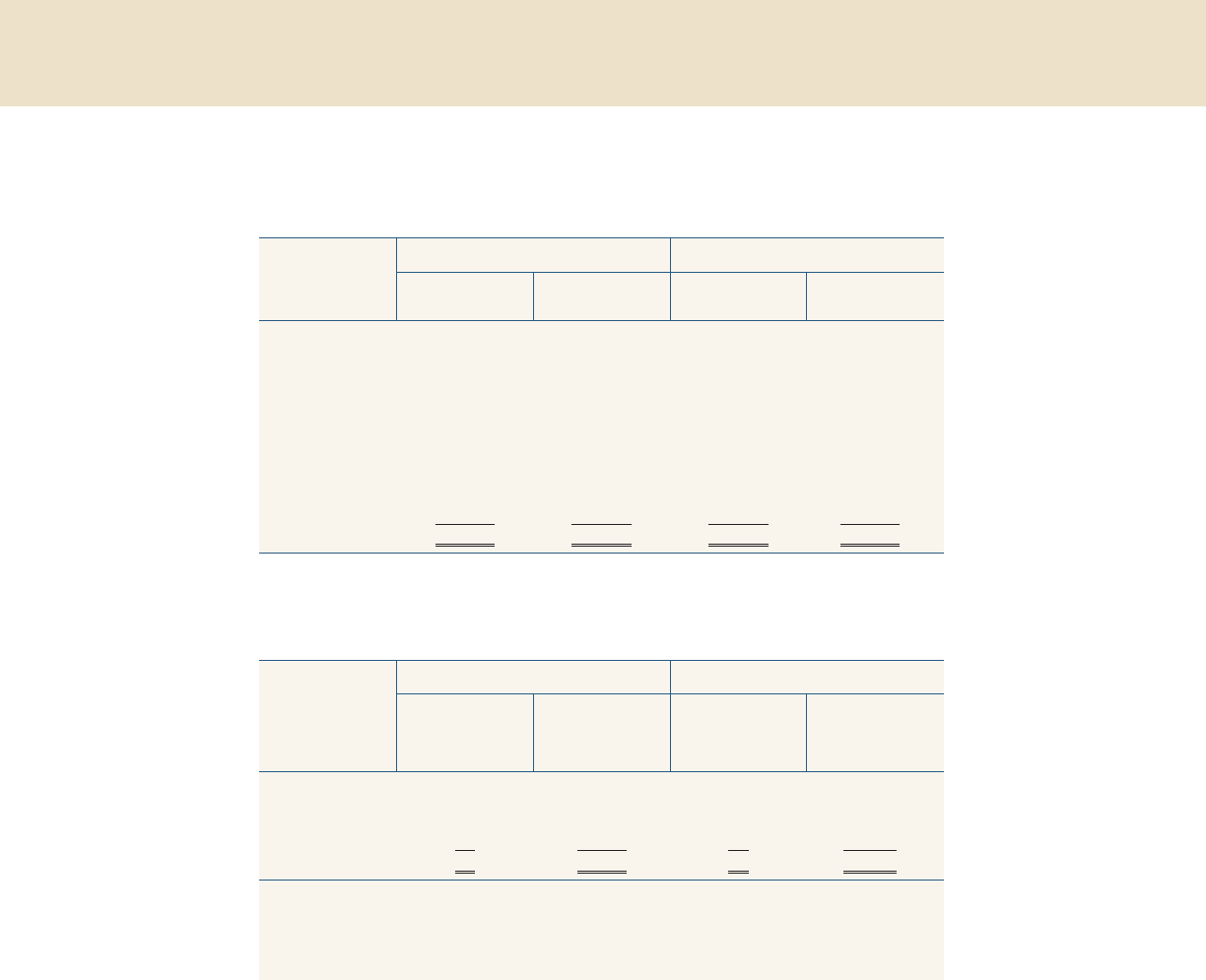

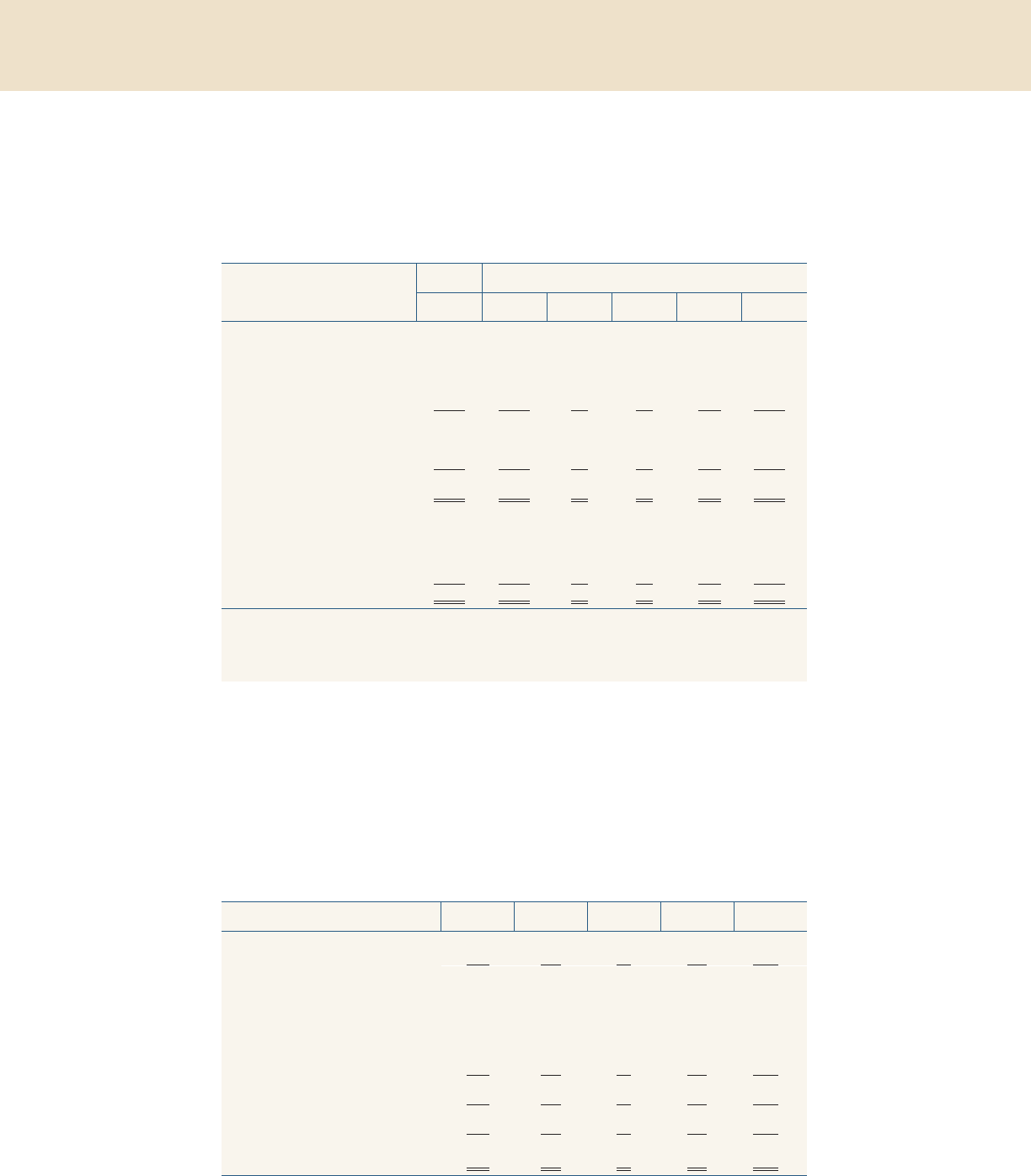

Statistical Tables

............. .............. .............. .............. . .............. .............. .............. .................. 287

Federal Reserve System Audits

............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ..... 317

Board of Governors Financial Statements ............ .............. .............. ........................... .............. 318

Federal Reserve Banks Combined Financial Statements ................ . .............. ........................... . 340

Office of Inspector General Activities ........ .............. .............. . ........................... .............. .......... 398

Government Accountability Office Reviews ...... .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ... 399

Federal Reserve System Budgets

............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .. 401

System Budgets Overview .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ..... 401

Board of Governors Budgets ................. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ............ 404

Federal Reserve Banks Budgets ..... .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ..... 408

Currency Budget .................... .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ............. 412

Federal Reserve System Organization

............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ...... 417

Board of Governors ............ .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ... 417

Federal Open Market Committee ..... .............. . .............. .............. ........................... .............. .... 422

Board of Governors Advisory Councils ............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. .. 424

Federal Reserve Banks and Branches ........................... .............. .............. .............. .............. ... 427

Index

............. .............. .............. .............. . .............. .............. .............. .............. .............. ........... 443

vi

Overview

The Federal Reserve, the central bank of the United

States, is a federal system composed of a central gov-

ernmental agency—the Board of Governors—and

12 regional Federal Reserve Banks.

The Board of Governors, located in Washington,

D.C., consists of seven members appointed by the

President of the United States and supported by a

2,745-person staff. Besides conducting research,

analysis, and policymaking related to domestic and

international financial and economic matters, the

Board plays a major role in the supervision and regu-

lation of U.S. financial institutions and activities, has

broad oversight responsibility for the nation’s pay-

ments system and the operations and activities of the

Federal Reserve Banks, and plays an important role

in promoting consumer protection, fair lending, and

community development.

About This Report

This report covers Board and System operations and

activities during calendar-year 2014. The report

includes the following sections:

•

Monetary policy and economic developments.

Section 2 provides adapted versions of the Board’s

semiannual monetary policy reports to Congress.

•

Federal Reserve operations.

Section 3 provides a

summary of Board and System activities in the

areas of financial stability policy and research;

sec-

tion 4

, in supervision and regulation; section 5, in

consumer and community affairs; and

section 6, in

Reserve Bank operations.

•

Dodd-Frank Act implementation and other require-

ments.

Section 7 summarizes the Board’s efforts in

2014 to implement provisions of the Dodd-Frank

Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

as well as the Board’s compliance with the Govern-

ment Performance and Results Act of 1993.

•

Policy actions and litigation.

Section 8 and

section 9 provide accounts of policy actions taken

by the Board in 2014, including new or amended

rules and regulations and other actions as well as

the deliberations and decisions of the Federal Open

Market Committee (FOMC);

1

section 10 summa-

rizes litigation involving the Board.

•

Statistical tables.

Section 11 includes 14 statistical

tables that provide updated historical data concern-

ing Board and System operations and activities.

•

Federal Reserve System audits.

Section 12 provides

detailed information on the several levels of audit

and review conducted in regards to System opera-

tions and activities, including those provided by

outside auditors and the Board’s Office of Inspec-

tor General.

•

Federal Reserve System budgets.

Section 13 presents

information on the 2014 budget performance of

the Board and Reserve Banks, as well as their 2015

budgets, budgeting processes, and trends in their

expenses and employment.

•

Federal Reserve System organization.

Section 14

provides listings of key officials at the Board and in

the Federal Reserve System, including the Board of

1

For more information on the FOMC, see the Board’s website at

www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomc.htm.

For More Background on

Board Operations

For more information about the Federal Reserve

Board and the Federal Reserve System, visit the

Board’s website at

www.federalreserve.gov/

aboutthefed/default.htm

. An online version of this

annual report is available at

www.federalreserve.gov/

publications/annual-report/default.htm

.

1

1

Governors, its officers, FOMC members, several

System councils, and Federal Reserve Bank and

Branch officers and directors.

About the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System, which serves as the

nation’s central bank, was created by an act of Con-

gress on December 23, 1913. The System consists of

a seven-member Board of Governors with headquar-

ters in Washington, D.C., and the 12 Reserve Banks

located in major cities throughout the United States.

The Federal Reserve Banks are the operating arms of

the central banking system, carrying out a variety of

System functions, including operating a nationwide

payment system; distributing the nation’s currency

and coin; under authority delegated by the Board of

Governors, supervising and regulating a variety of

financial institutions and activities; serving as fiscal

agents of the U.S. Treasury; and providing a variety

of financial services for the Treasury, other govern-

ment agencies, and other fiscal principals.

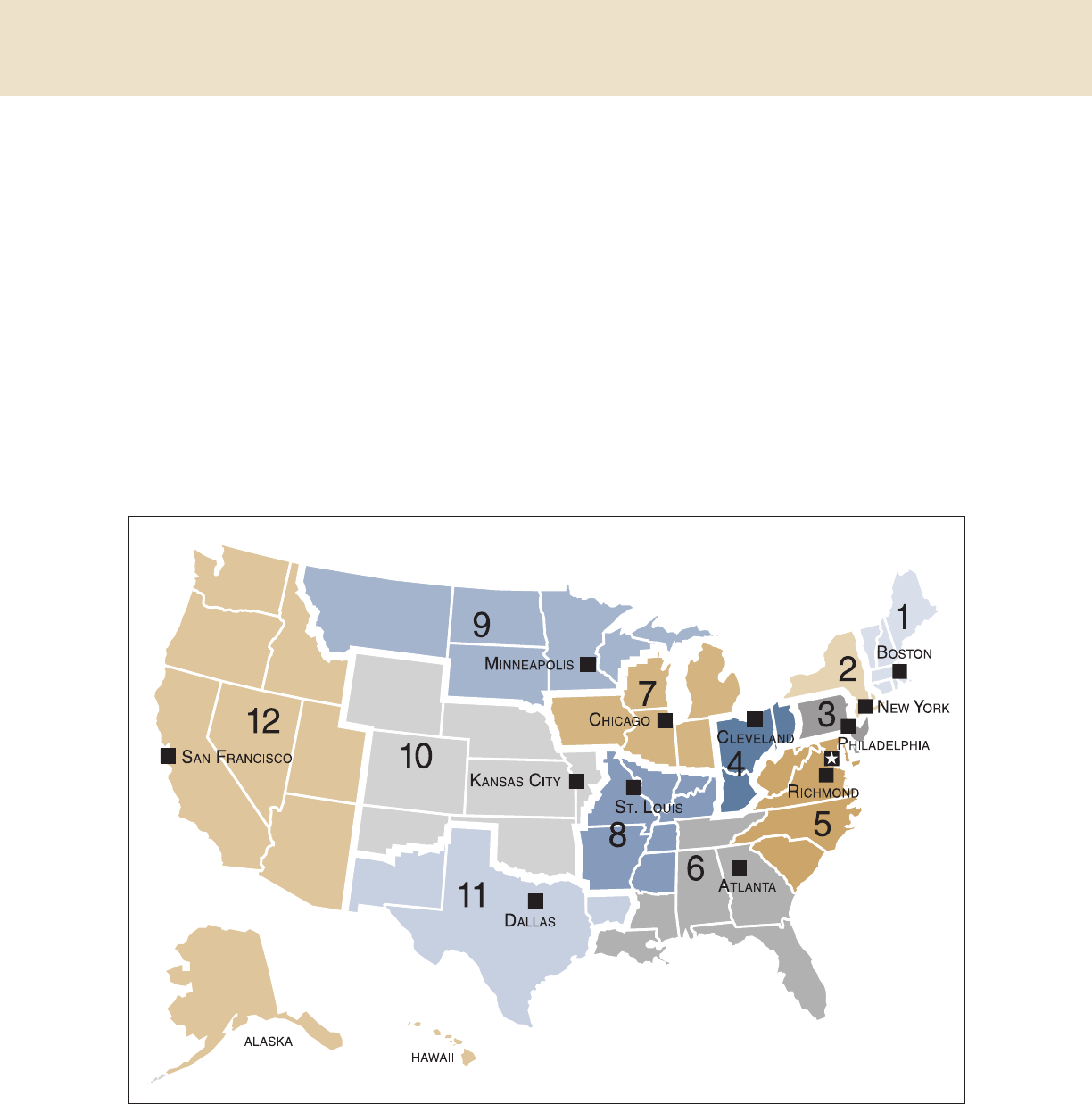

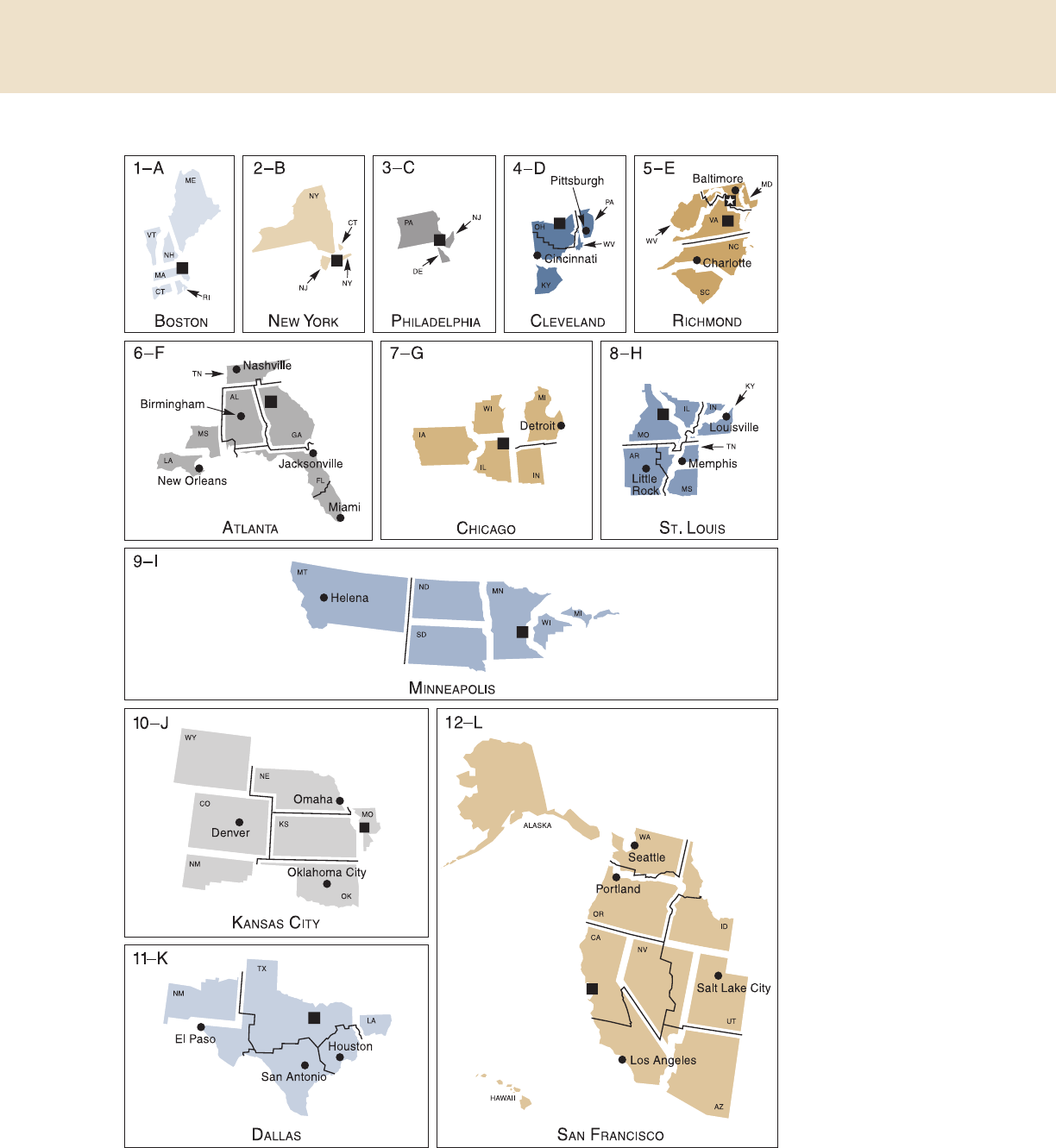

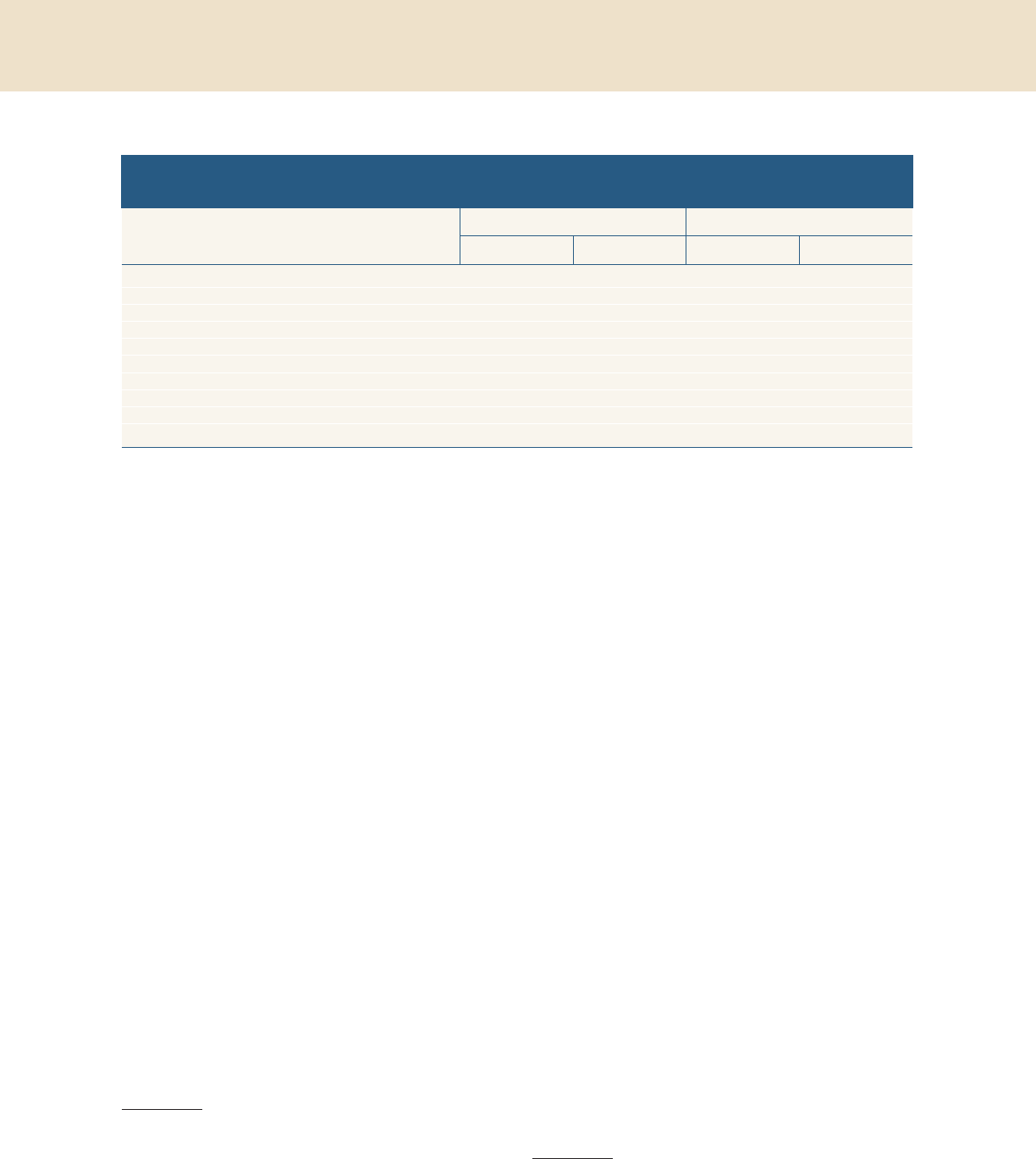

The following maps identify Federal Reserve Dis-

tricts by their official number, city, and letter

designation.

■ Federal Reserve Bank city

■

N

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, D.C.

2 101st Annual Report | 2014

■ Federal Reserve Bank city

● Federal Reserve Branch city

■

N

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, D.C.

— Branch boundary

Overview 3

Monetary Policy and

Economic Developments

As required by section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act,

the Federal Reserve Board submits written reports to

the Congress that contain discussions of “the con-

duct of monetary policy and economic developments

and prospects for the future.” The Monetary Policy

Report, submitted semiannually to the Senate Com-

mittee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs and

to the House Committee on Banking and Financial

Services, is delivered concurrently with testimony

from the Federal Reserve Board Chair.

The following discussion is a review of U.S. monetary

policy and economic developments in 2014, excerpted

from the Monetary Policy Reports published in Feb-

ruary 2015 and July 2014. Those complete reports

are available on the Board’s website at

www

.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/20150224_

mprfullreport.pdf

(February 2015) and www

.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/20140715_

mprfullreport.pdf

(July 2014).

Other materials in this annual report related to the

conduct of monetary policy can be found in

sec-

tion 9

, “Minutes of Federal Open Market Committee

Meetings,” and

section 11, “Statistical Tables” (see

tables 1–4).

Monetary Policy Report

of February 2015

Summary

The labor market improved further during the second

half of last year and into early 2015, and labor mar-

ket conditions moved closer to those the Federal

Open Market Committee (FOMC) judges consistent

with its maximum employment mandate. Since the

middle of last year, monthly payrolls have expanded

by about 280,000, on average, and the unemployment

rate has declined nearly ½ percentage point on net.

Nevertheless, a range of labor market indicators sug-

gest that there is still room for improvement. In par-

ticular, at 5.7 percent, the unemployment rate is still

above most FOMC participants’ estimates of its

longer-run normal level, the labor force participation

rate remains below most assessments of its trend, an

unusually large number of people continue to work

part time when they would prefer full-time employ-

ment, and wage growth has continued to be slow.

A steep drop in crude oil prices since the middle of

last year has put downward pressure on overall infla-

tion. As of December 2014, the price index for per-

sonal consumption expenditures was only ¾ percent

higher than a year earlier, a rate of increase that is

well below the FOMC’s longer-run goal of 2 percent.

Even apart from the energy sector, price increases

have been subdued. Indeed, the prices of items other

than food and energy products rose at an annual rate

of only about 1 percent over the last six months of

2014, noticeably less than in the first half of the year.

The slow pace of price increases during the second

half was likely associated, in part, with falling import

prices and perhaps also with some pass-through of

lower oil prices. Survey-based measures of longer-

term inflation expectations have remained stable;

however market-based measures of inflation com-

pensation have declined since last summer.

Economic activity expanded at a strong pace in the

second half of last year. Notably reflecting solid

gains in consumer spending, real gross domestic

product (GDP) is estimated to have increased at an

annual rate of 3¾ percent after a reported increase of

just 1¼ percent in the first half of the year. The

growth in GDP was supported by accommodative

monetary policy, a reduction in the degree of

restraint imparted by fiscal policy, and the increase in

households’ purchasing power arising from the drop

in oil prices. The gains in GDP have occurred despite

continued sluggish growth abroad and a sizable

appreciation of the U.S. dollar, both of which have

weighed on net exports.

Financial conditions in the United States have gener-

ally remained supportive of economic growth.

Longer-term interest rates in the United States and

5

2

other advanced economies have continued to move

down, on net, since the middle of 2014 amid disap-

pointing economic growth and low inflation abroad

as well as the associated anticipated and actual mon-

etary policy actions by foreign central banks. Broad

indexes of U.S. equity prices have risen moderately,

on net, since the end of June. Credit flows to nonfi-

nancial businesses largely remained solid in the sec-

ond half of last year. Overall borrowing conditions

for households eased further, but mortgage lending

standards are still tight for many potential borrowers.

The vulnerability of the U.S. financial system to

financial instability has remained moderate, primarily

reflecting low-to-moderate levels of leverage and

maturity transformation. Asset valuation pressures

have eased a little, on balance, but continue to be

notable in some sectors. The capital and liquidity

positions of the banking sector have improved fur-

ther. Over the second half of 2014, the Federal

Reserve and other agencies finalized or proposed sev-

eral more rules related to the Dodd-Frank Wall Street

Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010,

which were designed to further strengthen the resil-

ience of the financial system.

At the time of the FOMC meeting in late January of

this year, the Committee saw the outlook as broadly

similar to that at the time of its December meeting,

when the most recent Summary of Economic Projec-

tions (SEP) was compiled. (The December SEP is

included as

Part 3 of the February 2015 Monetary

Policy Report on pages 39–52; it is also included in

section 9 of this annual report.) The FOMC expects

that, with appropriate monetary policy accommoda-

tion, economic activity will expand at a moderate

pace, and that labor market indicators will continue

to move toward levels the Committee judges consis-

tent with its dual mandate of maximum employment

and price stability. In addition, the Committee con-

tinues to see the risks to the outlook for economic

activity and the labor market as nearly balanced.

Inflation is anticipated to decline further in the near

term, mainly reflecting the pass-through of lower oil

prices to consumer energy prices. However, the Com-

mittee expects inflation to rise gradually toward its

2 percent longer-run objective over the medium term

as the labor market improves further and the transi-

tory effects of lower energy prices and other factors

dissipate.

At the end of October, and after having made further

measured reductions in the pace of its asset pur-

chases at its July and September meetings, the

FOMC concluded the asset purchase program that

began in September 2012. The decision to end the

purchase program reflected the substantial improve-

ment in the outlook for the labor market since the

program’s inception—the stated aim of the asset pur-

chases—and a judgment that the underlying strength

of the broader economy was sufficient to support

ongoing progress toward the Committee’s policy

objectives.

Nonetheless, the Committee continued to judge that

a high degree of policy accommodation remained

appropriate. As a result, the FOMC has maintained

the exceptionally low target range of 0 to ¼ percent

for the federal funds rate and kept the Federal

Reserve’s holdings of longer-term securities at sizable

levels. The Committee has also continued to provide

forward guidance bearing on the anticipated path of

the federal funds rate. In particular, the FOMC has

stressed that in deciding how long to maintain the

current target range, it will consider a broad set of

indicators to assess realized and expected progress

toward its objectives. On the basis of its assessment,

the Committee indicated in its two most recent post-

meeting statements that it can be patient in beginning

to normalize the stance of monetary policy.

To further emphasize the data-dependent nature of

its policy stance, the FOMC has stated that if incom-

ing information indicates faster progress toward its

policy objectives than the Committee currently

expects, increases in the target range for the federal

funds rate will likely occur sooner than the Commit-

tee anticipates. The FOMC has also indicated that in

the case of slower-than-expected progress, increases

in the target range will likely occur later than cur-

rently anticipated. Moreover, the Committee contin-

ues to expect that, even after employment and infla-

tion are near mandate-consistent levels, economic

conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the

target federal funds rate below levels the Committee

views as normal in the longer run.

As part of prudent planning, the Federal Reserve has

continued to prepare for the eventual normalization

of the stance and conduct of monetary policy. The

FOMC announced updated principles and plans for

the normalization process following its September

meeting and has continued to test the operational

readiness of its monetary policy tools. The Commit-

tee remains confident that it has the tools it needs to

raise short-term interest rates when doing so becomes

appropriate, despite the very large size of the Federal

Reserve’s balance sheet.

6 101st Annual Report | 2014

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial

Developments

The labor market continued to improve in the second

half of last year and early this year. Job gains have

averaged close to 280,000 per month since June, and

the unemployment rate fell from 6.1 percent in June

to 5.7 percent in January. Even so, the labor market

likely has not yet fully recovered, and wage growth

has remained slow. Since June, a steep drop in crude

oil prices has exerted downward pressure on overall

inflation, and non-energy price increases have been

subdued as well. The price index for personal con-

sumption expenditures (PCE) increased only ¾ per-

cent during the 12 months ending in December, a

rate that is well below the Federal Open Market

Committee’s (FOMC) longer-run objective of 2 per-

cent; the index excluding food and energy prices was

up 1¼ percent over this period. Survey measures of

longer-run inflation expectations have been stable,

but measures of inflation compensation derived from

financial market quotes have moved down. Mean-

while, real gross domestic product (GDP) increased

at an estimated annual rate of 3¾ percent in the sec-

ond half of the year, up from a reported rate of just

1¼ percent in the first half. The growth in GDP has

been supported by accommodative monetary policy

and generally favorable financial conditions, the

boost to households’ purchasing power from lower

oil prices, and improving consumer and business con-

fidence. However, housing market activity has been

advancing only slowly, and sluggish growth abroad

and the higher foreign exchange value of the dollar

have weighed on net exports. Longer-term interest

rates in the United States and other advanced econo-

mies declined, on net, amid disappointing growth

and low inflation abroad and the associated actual

and anticipated accommodative monetary policy

actions by foreign central banks.

Domestic Developments

The labor market has strengthened further . . .

Employment rose appreciably and the unemployment

rate fell in the second half of 2014 and early this year.

Payroll employment has increased by an average of

about 280,000 per month since June, almost 40,000

faster than in the first half of last year (

figure 1). The

gain in payroll employment for 2014 as a whole was

the largest for any year since 1999. In addition, the

unemployment rate continued to move down, declin-

ing from 6.1 percent in June to 5.7 percent in January

of this year, a rate more than 4 percentage points

below its peak in 2009. Furthermore, a substantial

portion of the decline in unemployment over the past

year came from a decrease in the number of indi-

viduals reporting unemployment spells longer than

six months.

The labor force participation rate has been roughly

flat since late 2013 after having declined not only dur-

ing the recession, but also during much of the recov-

ery period when most other indicators of labor mar-

ket health were improving. While much of that

decline likely reflected ongoing demographic

trends—such as the aging of members of the baby-

boom generation into their retirement years—some

of the decline likely reflected workers’ perceptions of

poor job opportunities. Judged against the backdrop

of a declining trend, the recent stability of the par-

ticipation rate likely represents some cyclical

improvement. Nevertheless, the participation rate

remains lower than would be expected given the

unemployment rate, and thus it continues to suggest

more cyclical weakness than is indicated by the

unemployment rate.

Another sign that the labor market remains weaker

than indicated by the unemployment rate alone is the

still-elevated share of workers who are employed part

time but would like to work full time. This share of

involuntary part-time employees has generally shown

less improvement than the unemployment rate over

the past few years; in part for this reason, the more

comprehensive U-6 measure of labor underutiliza-

tion remains quite elevated (

figure 2).

Nevertheless, most broad measures of labor market

health have improved. With employment rising

and the participation rate holding steady, the

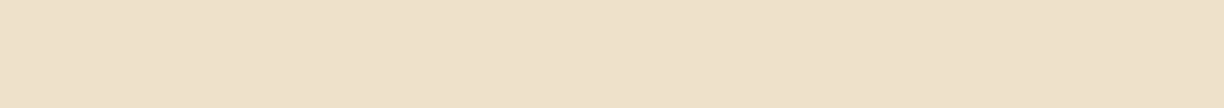

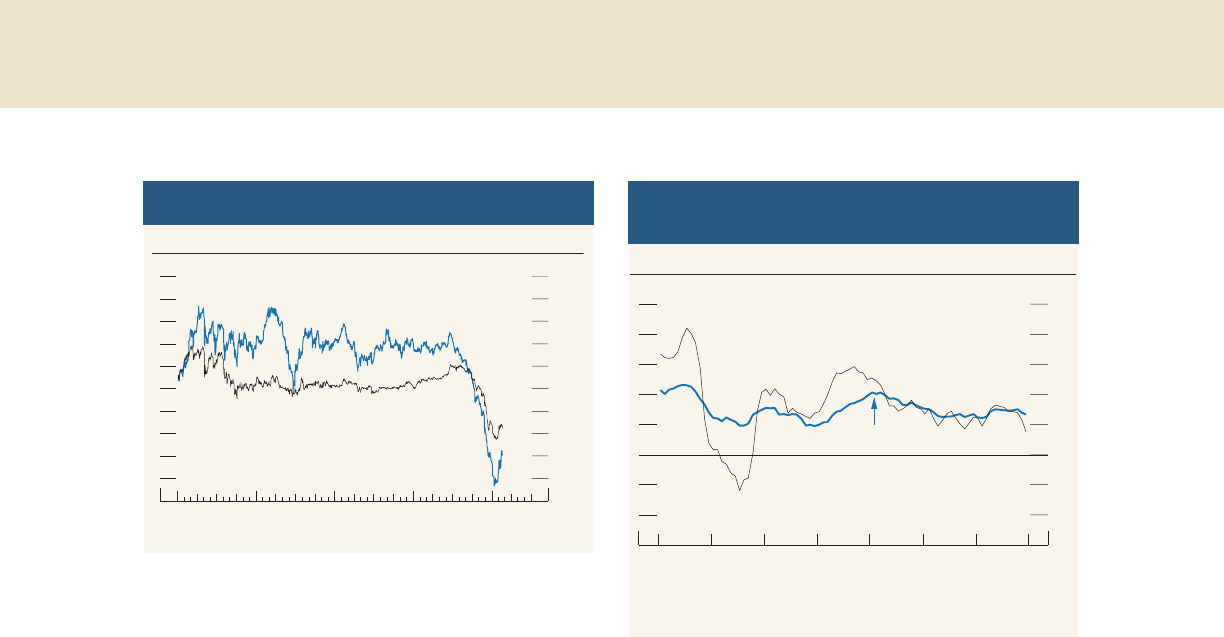

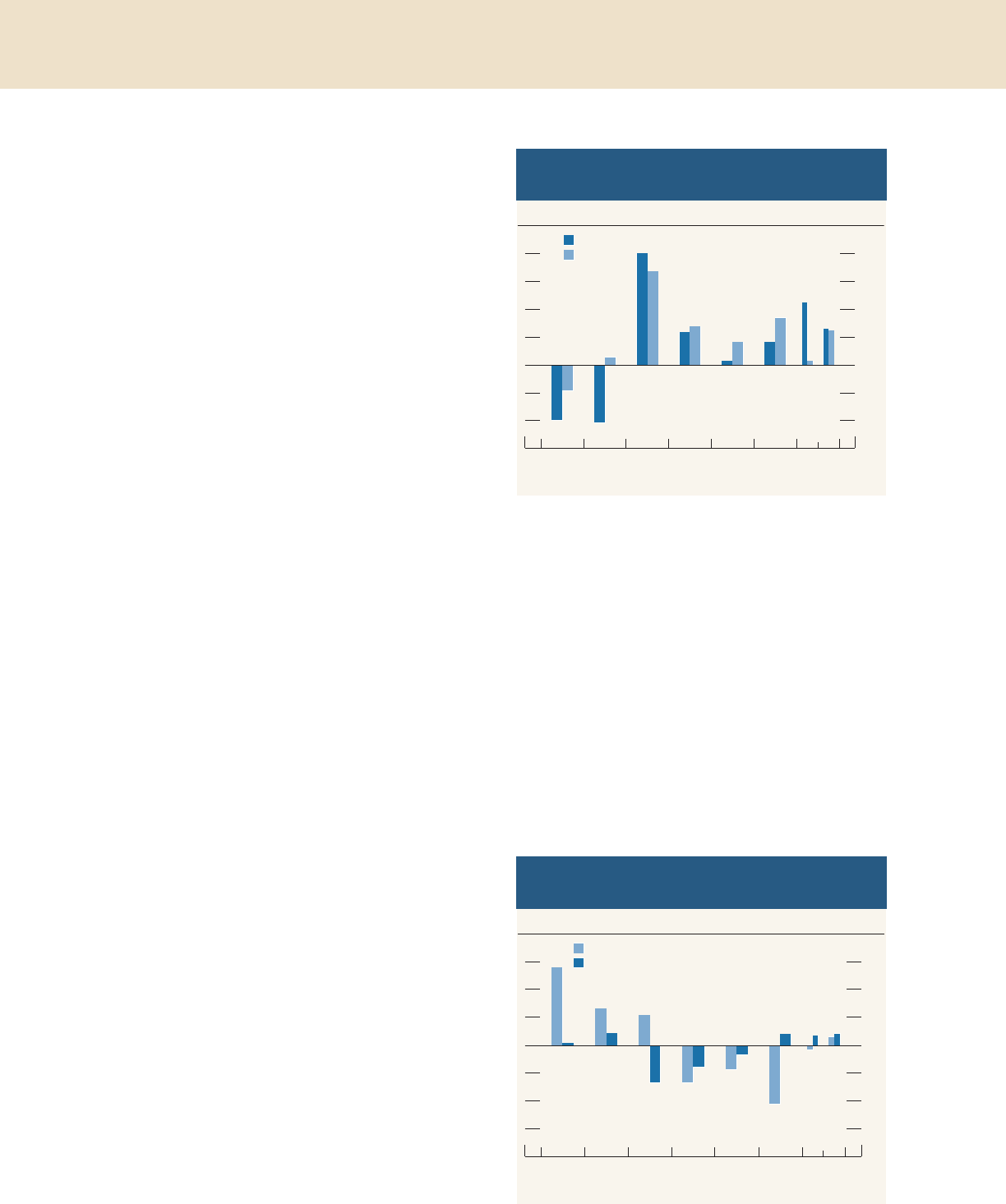

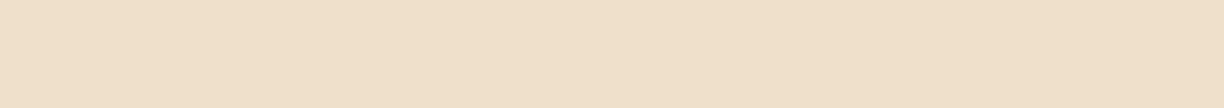

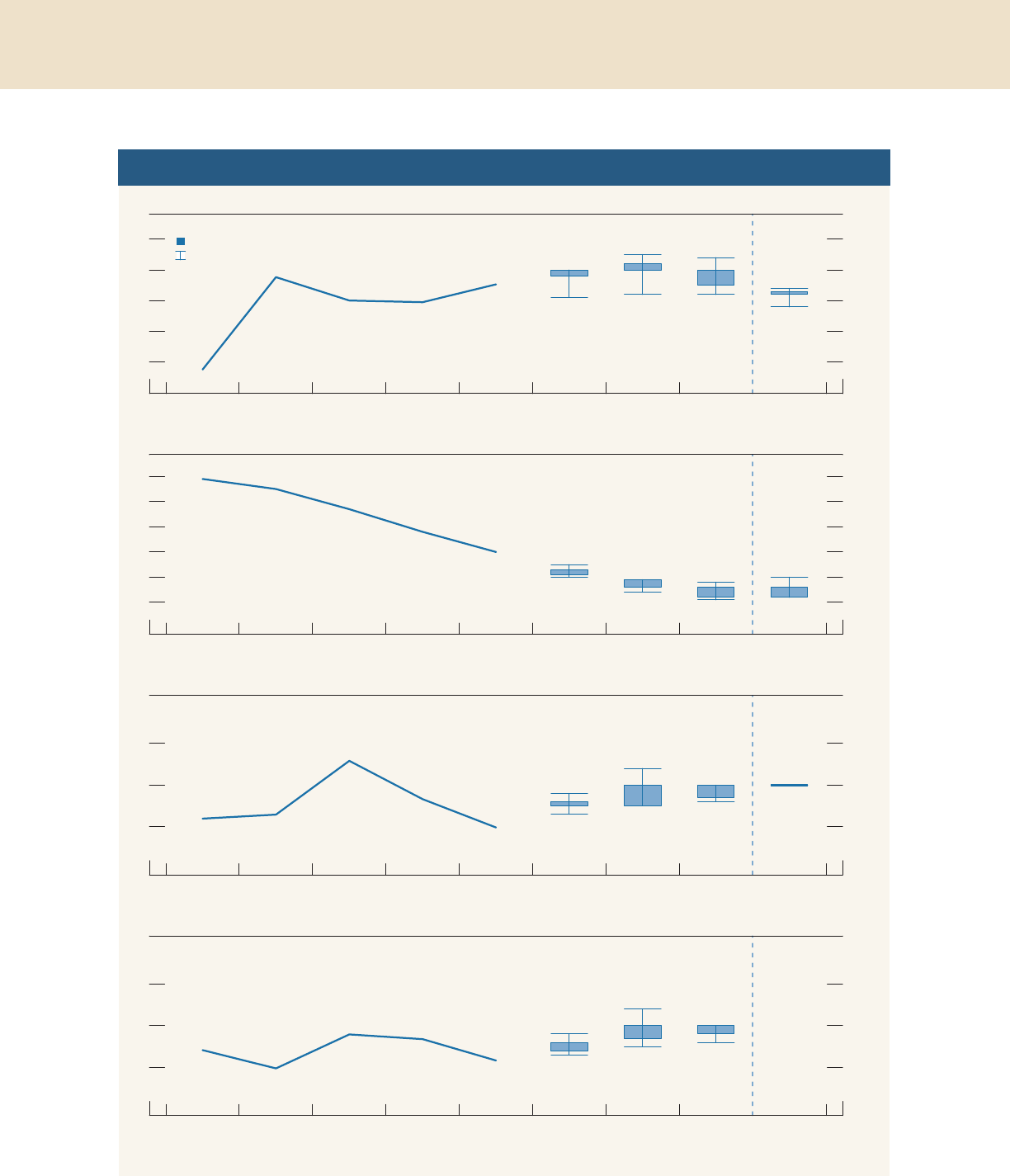

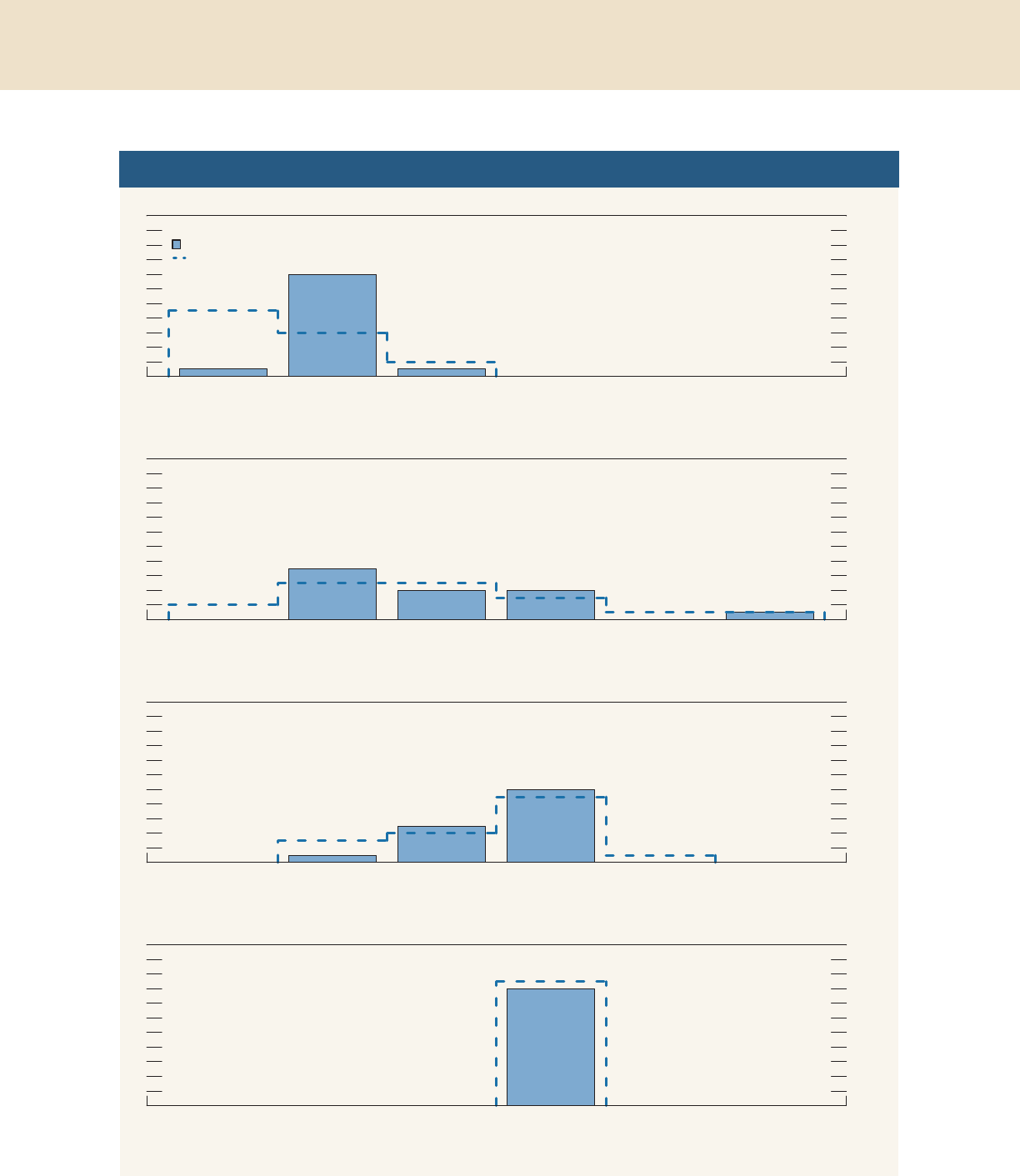

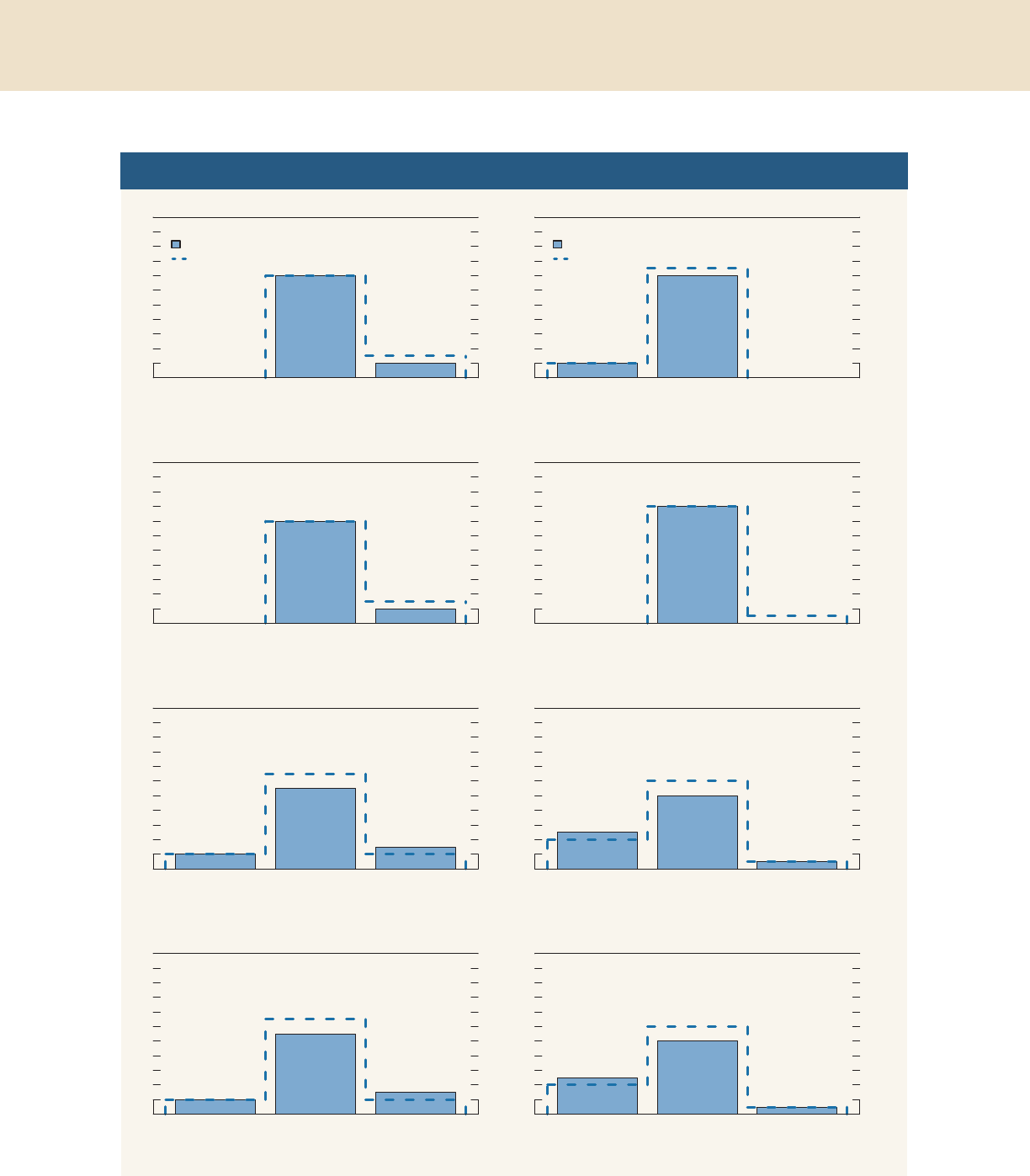

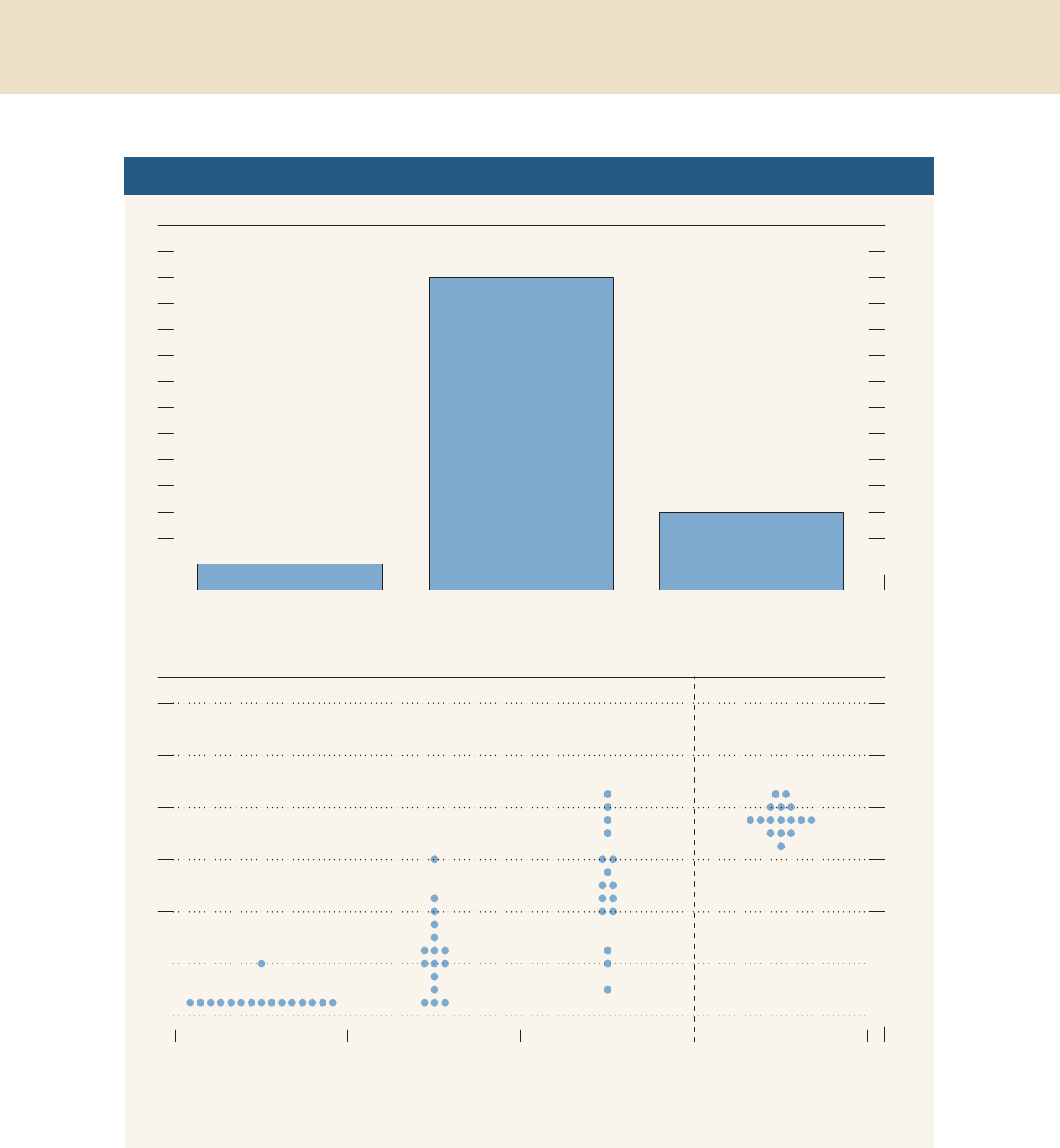

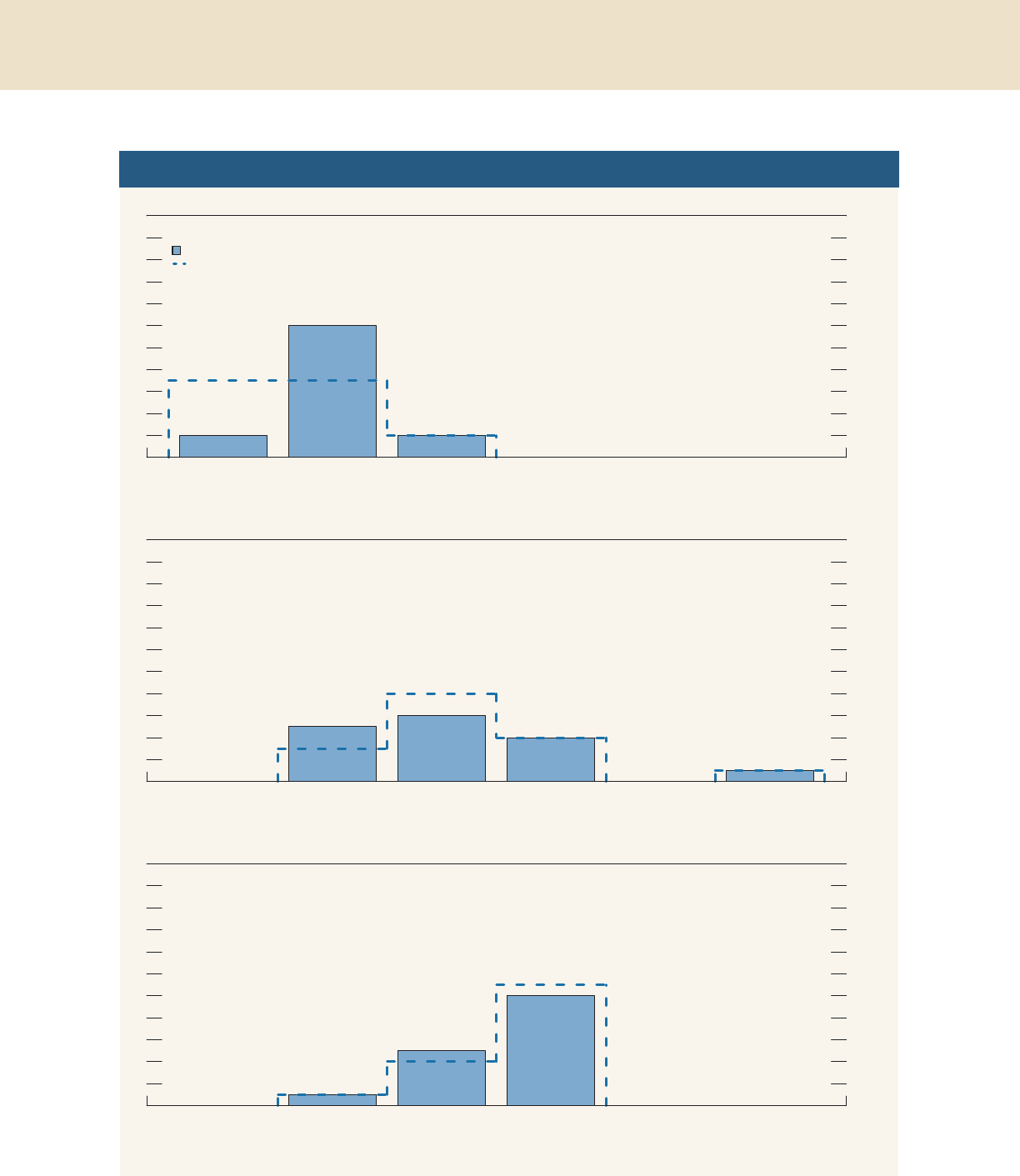

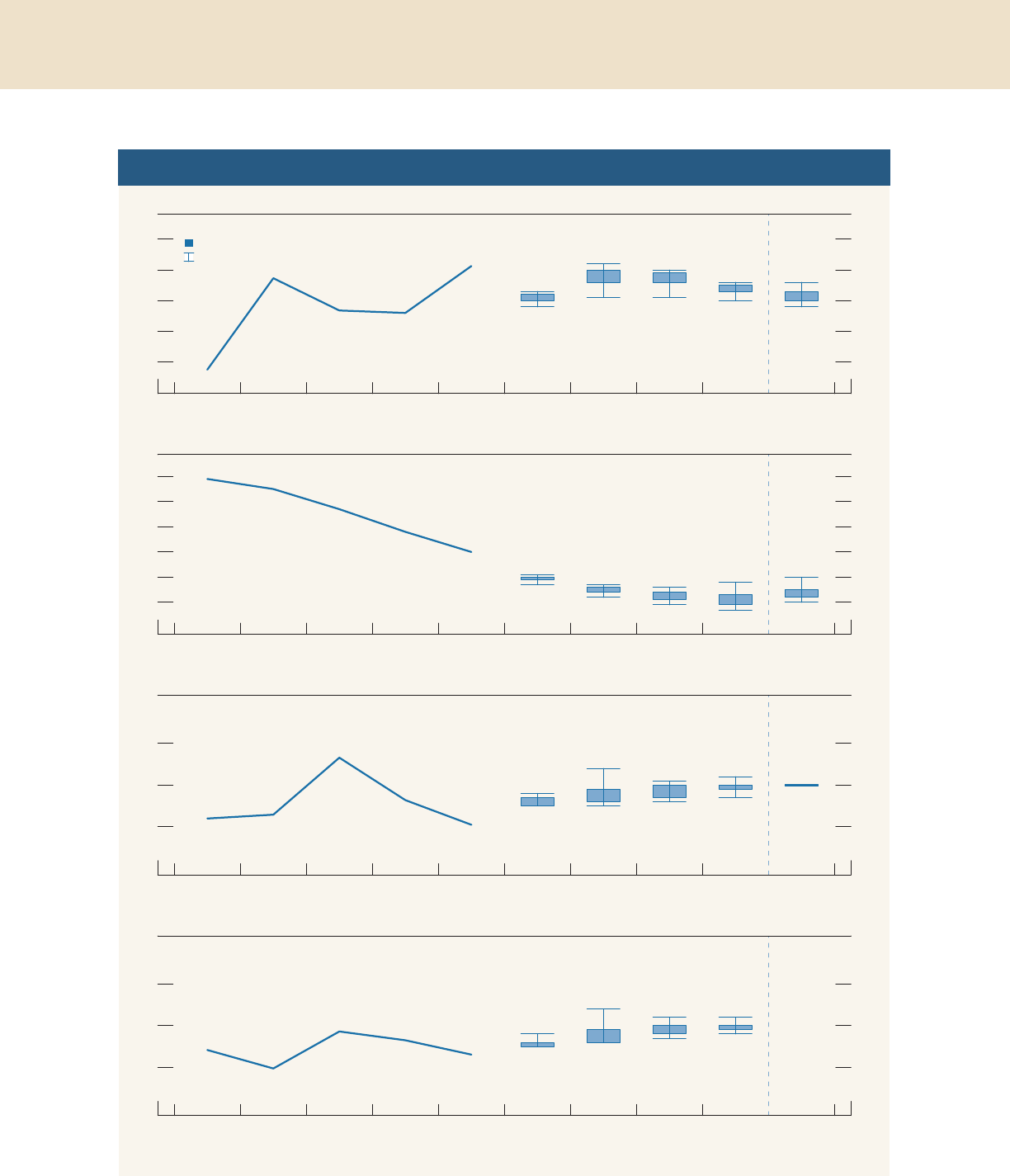

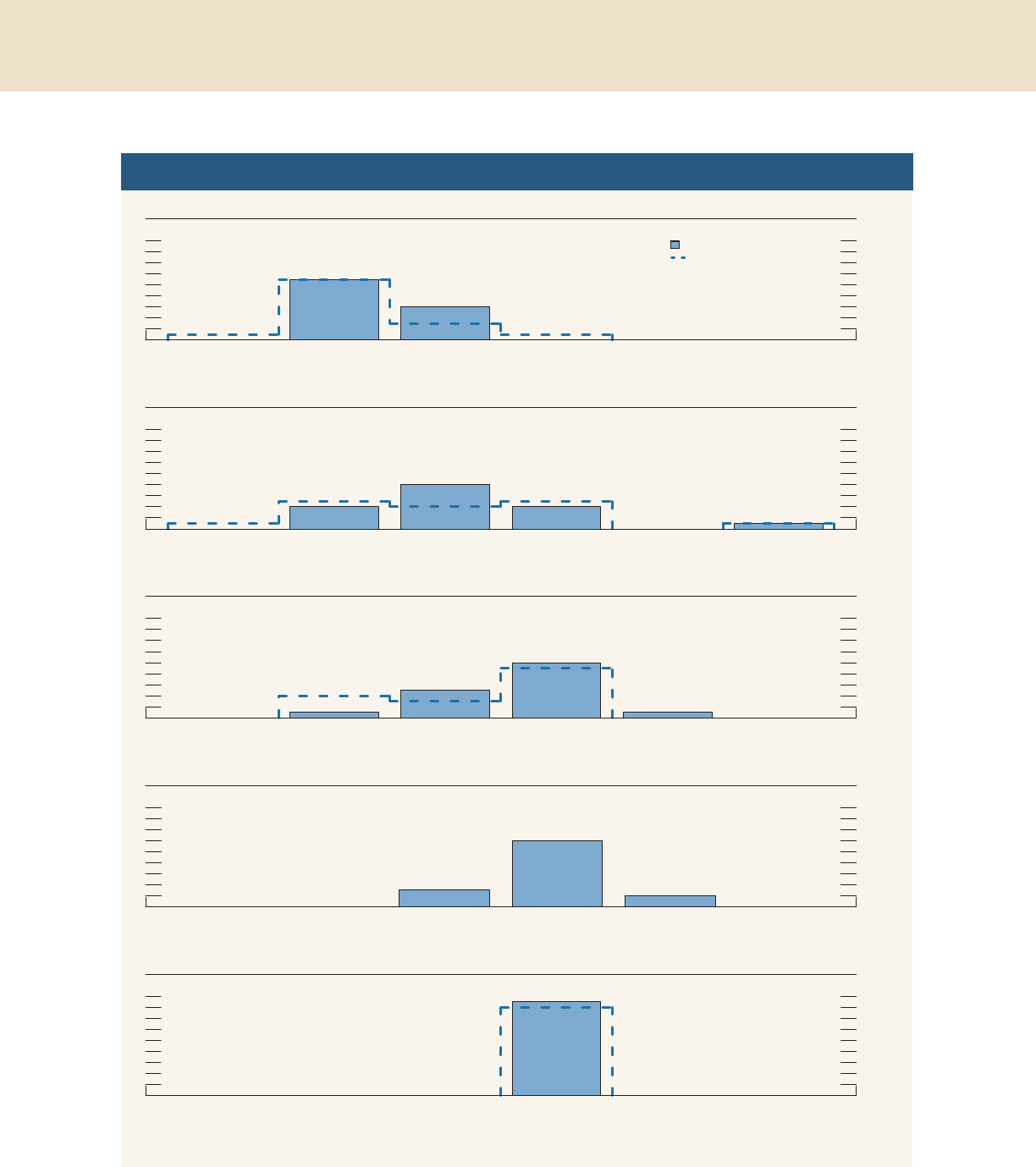

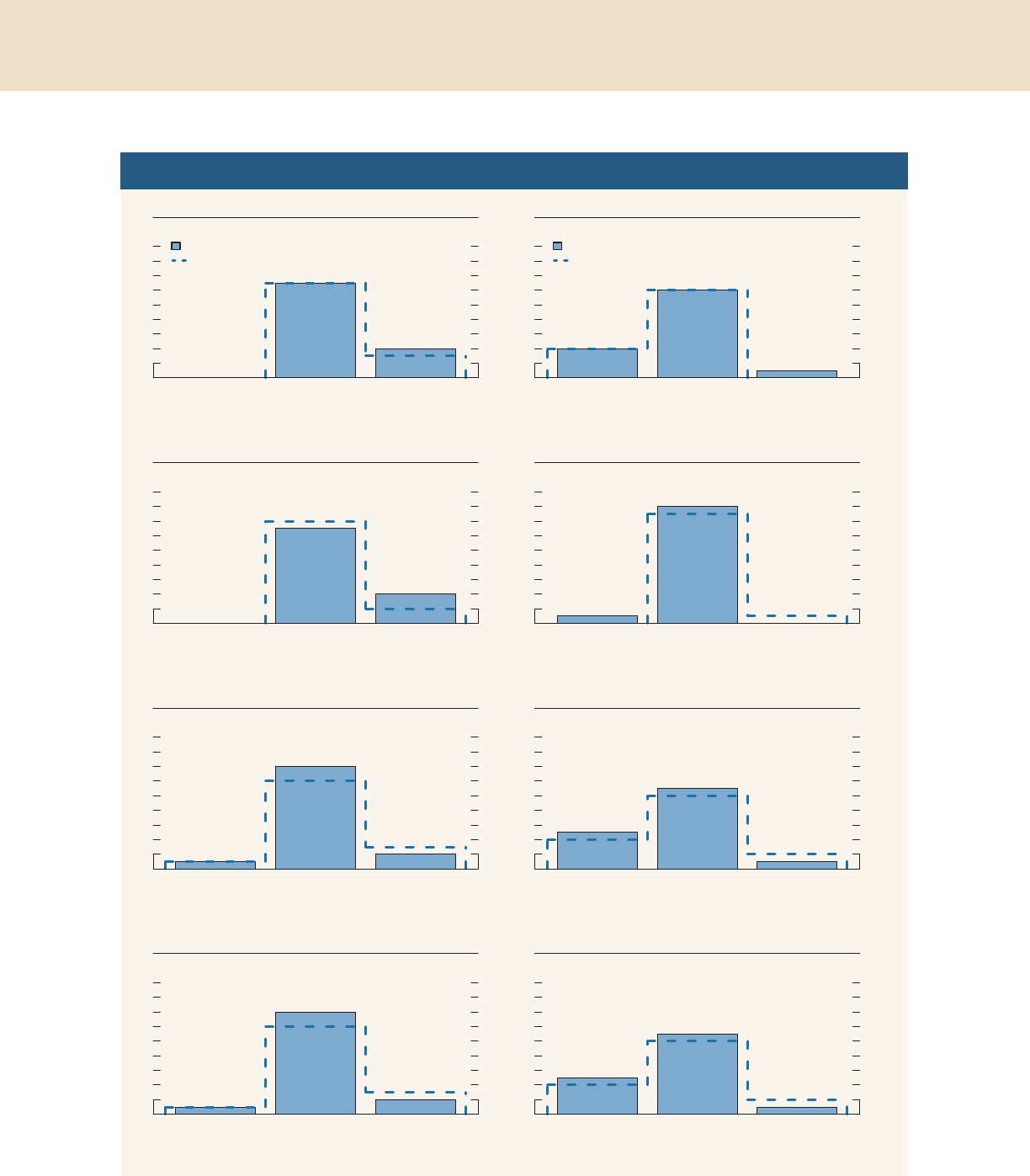

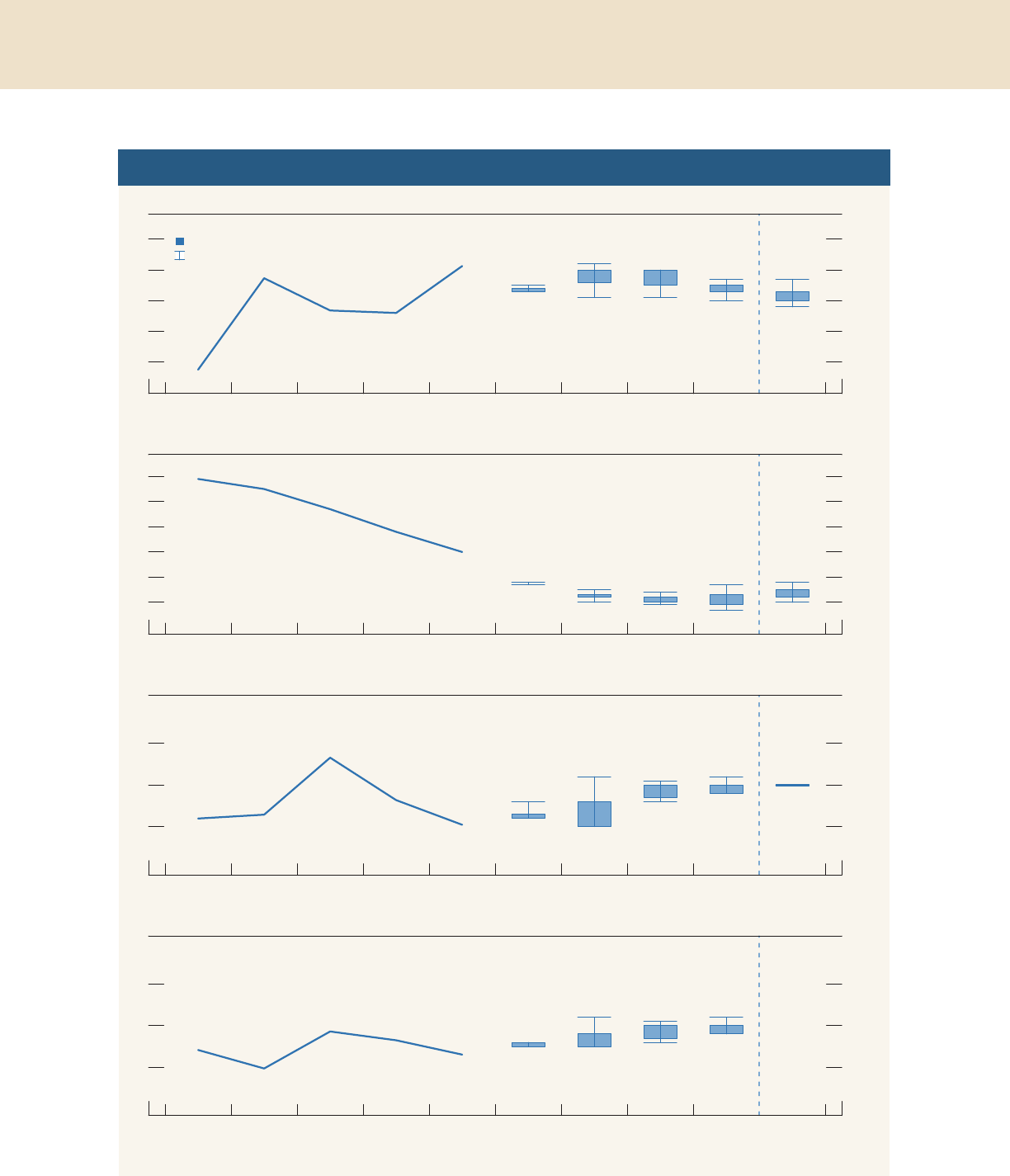

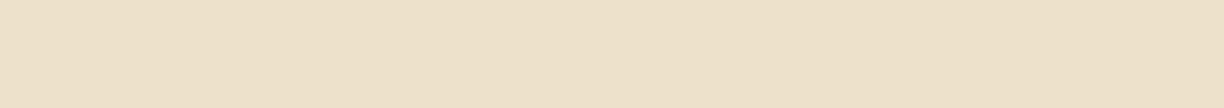

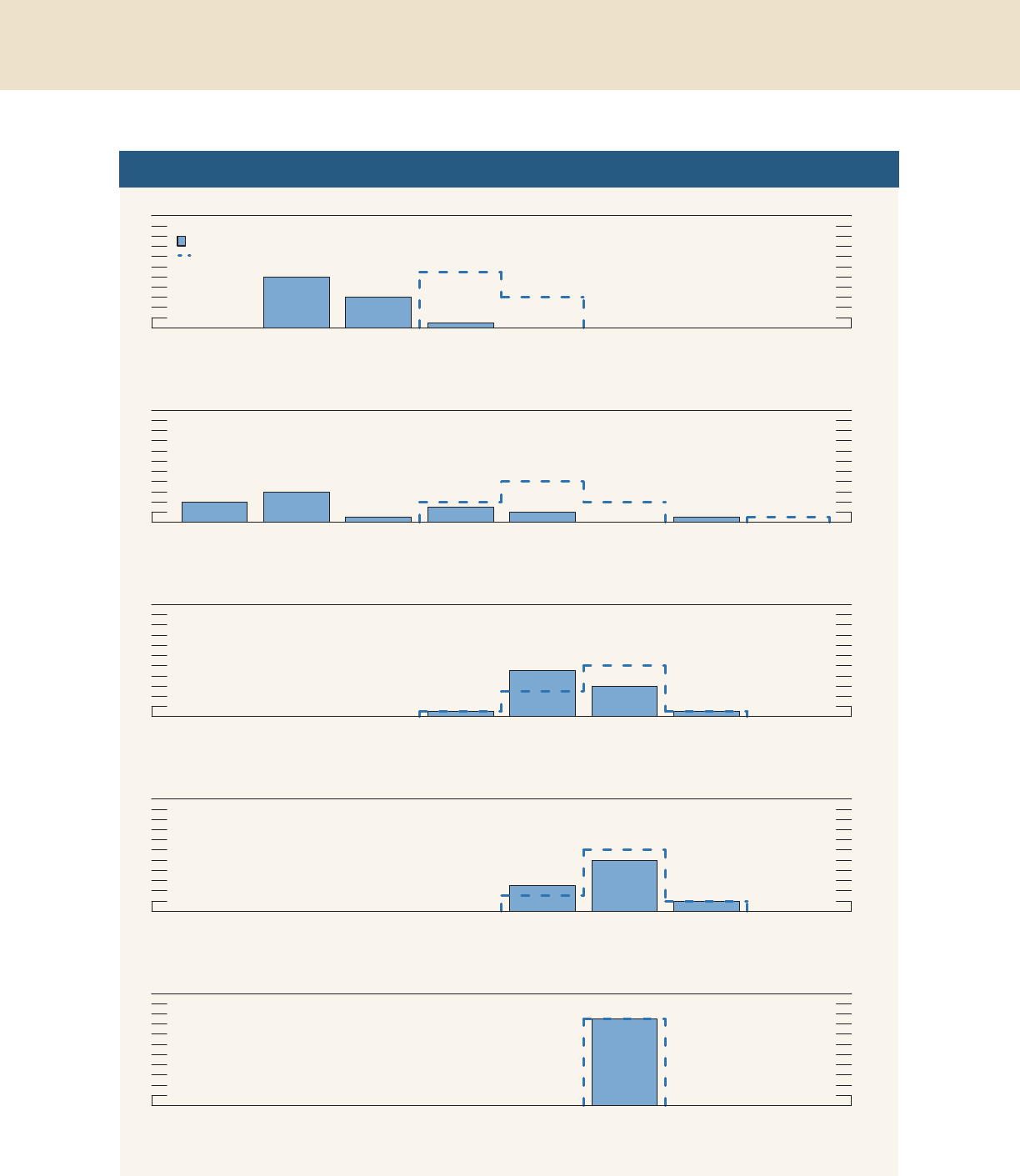

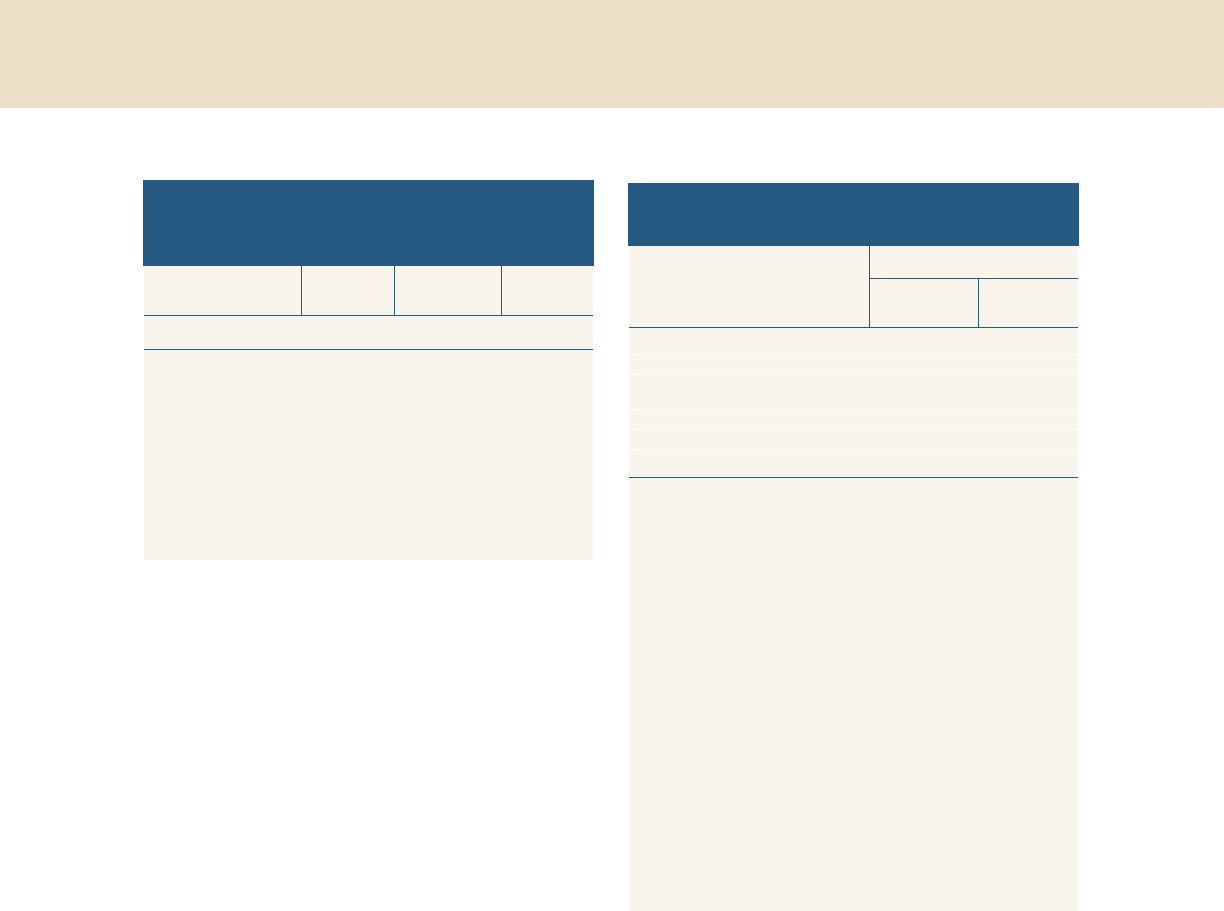

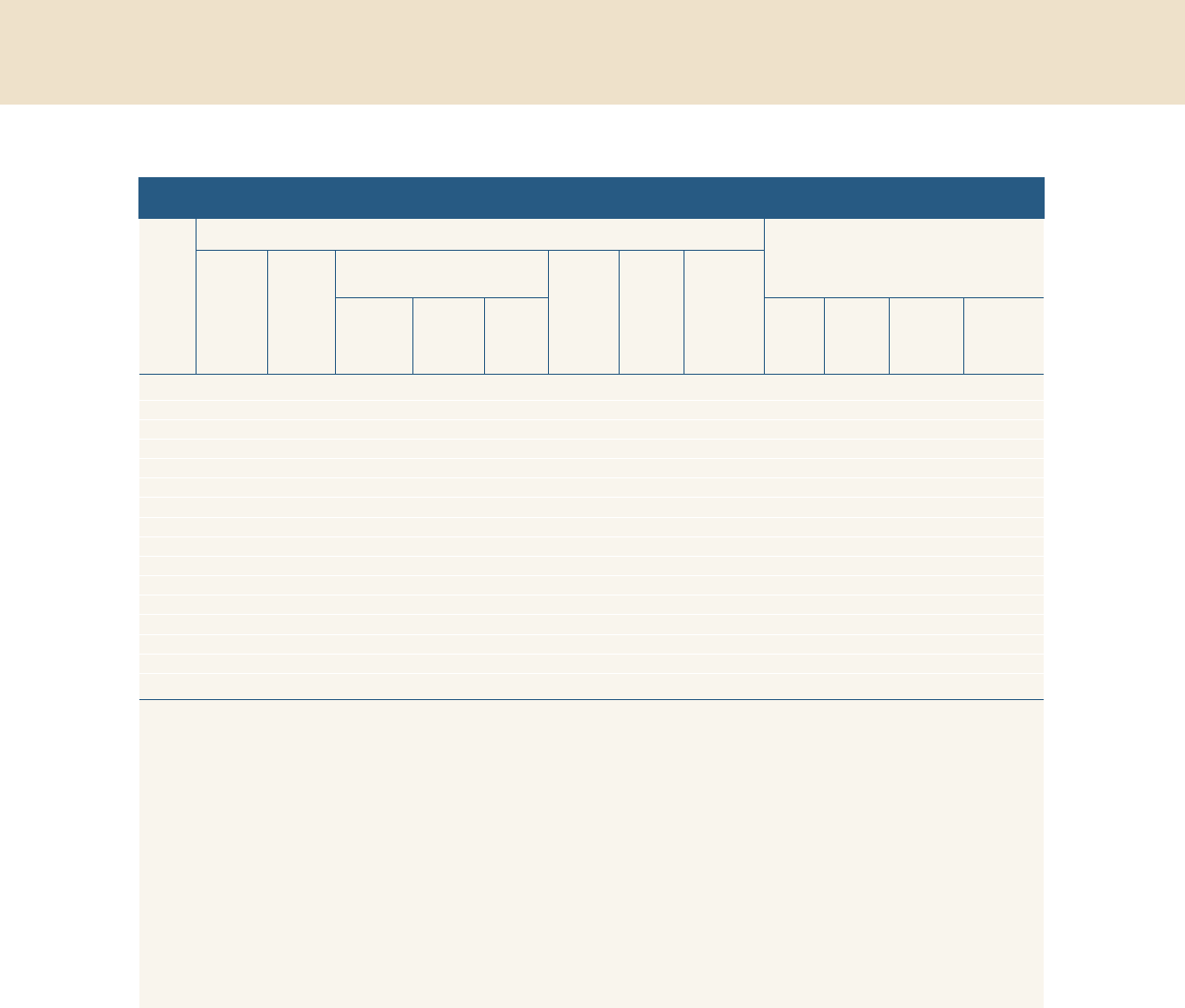

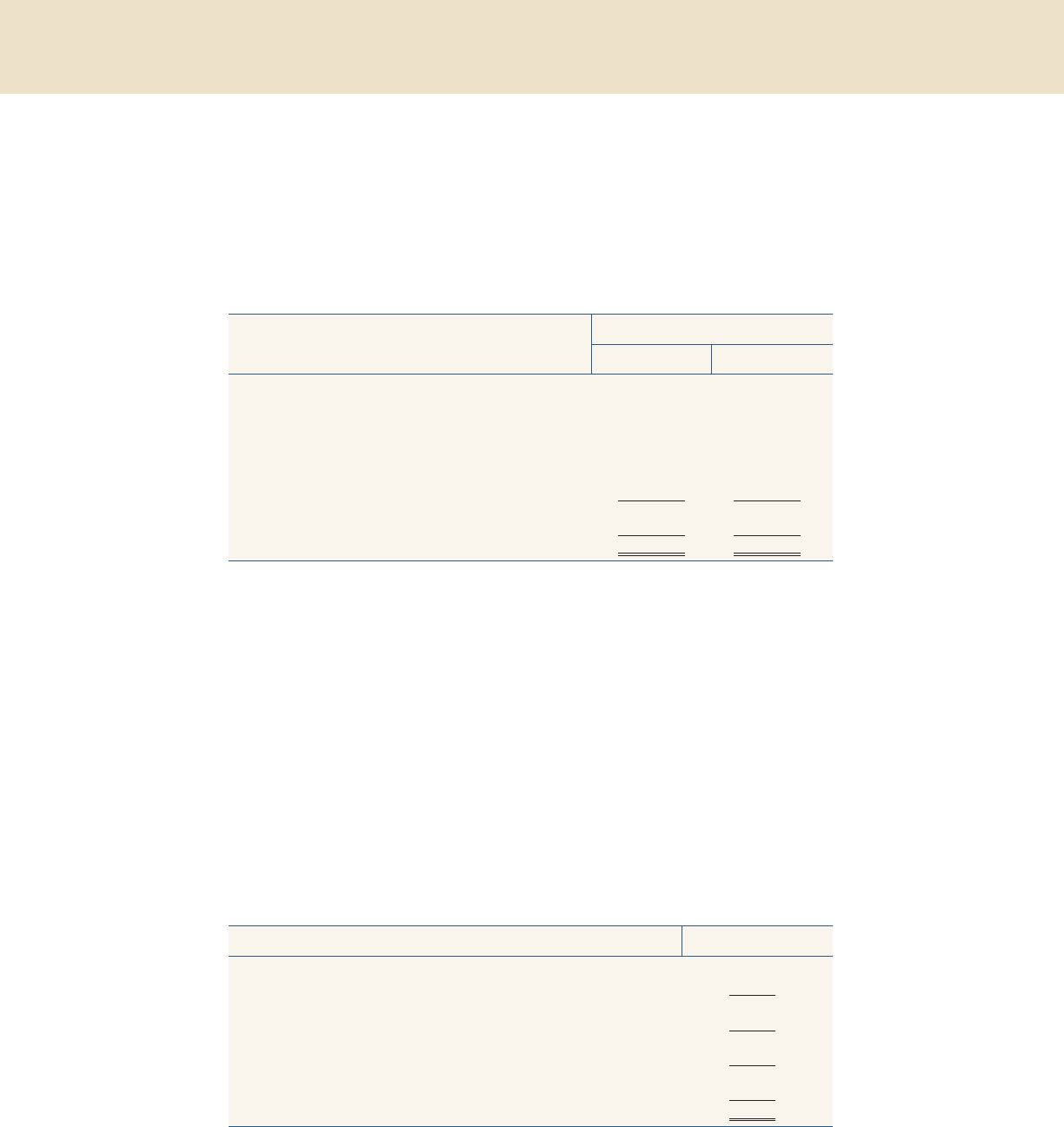

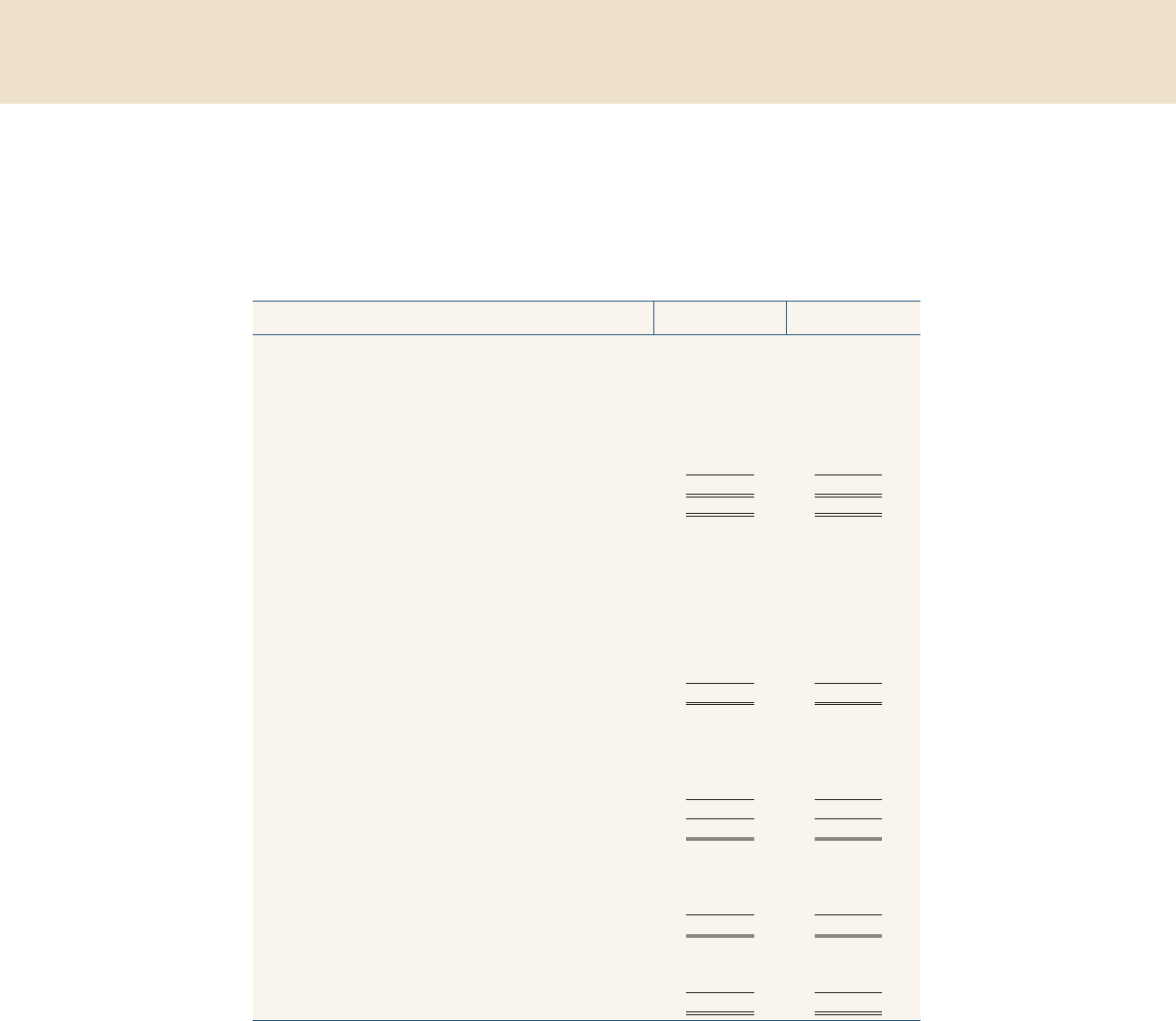

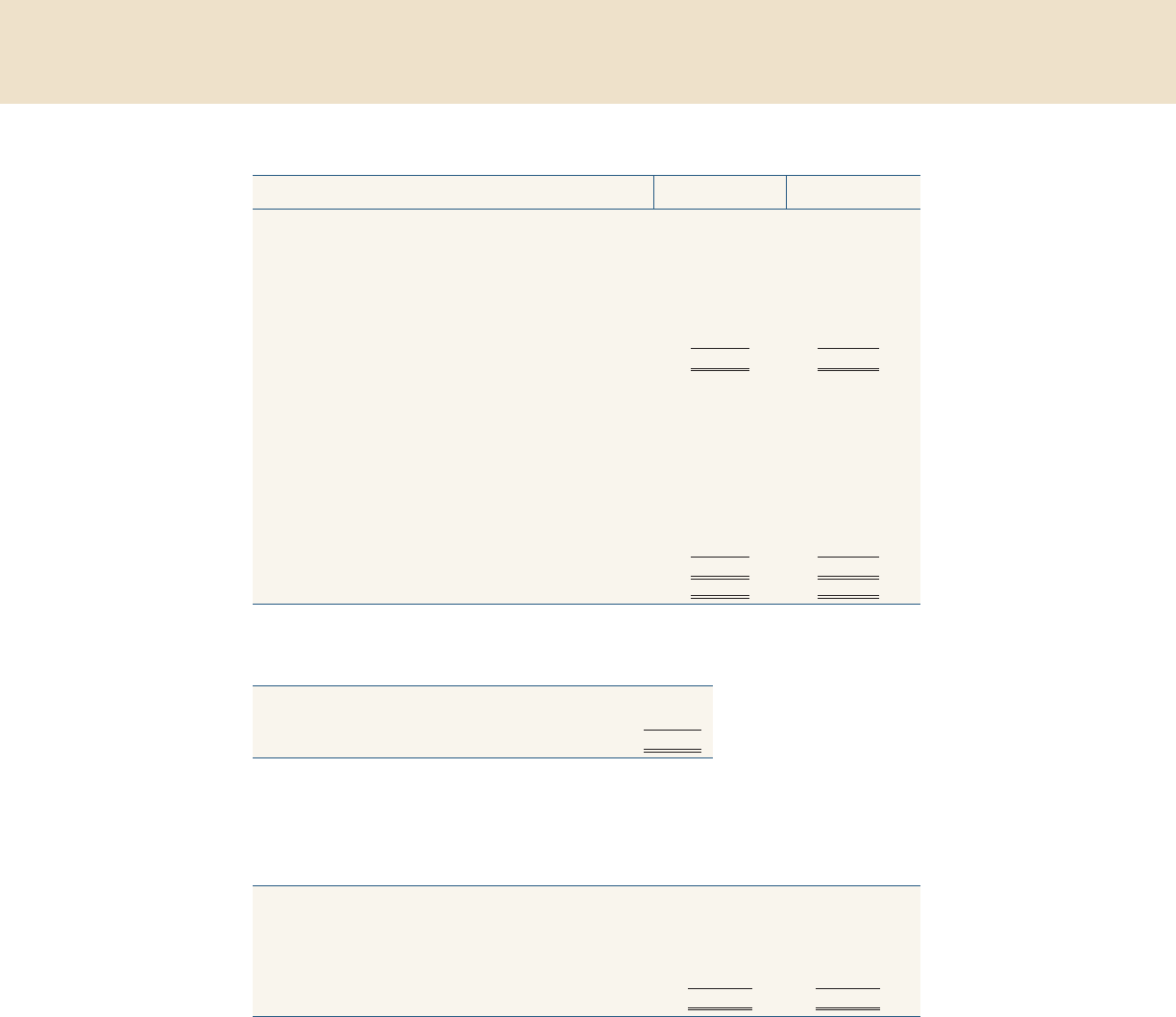

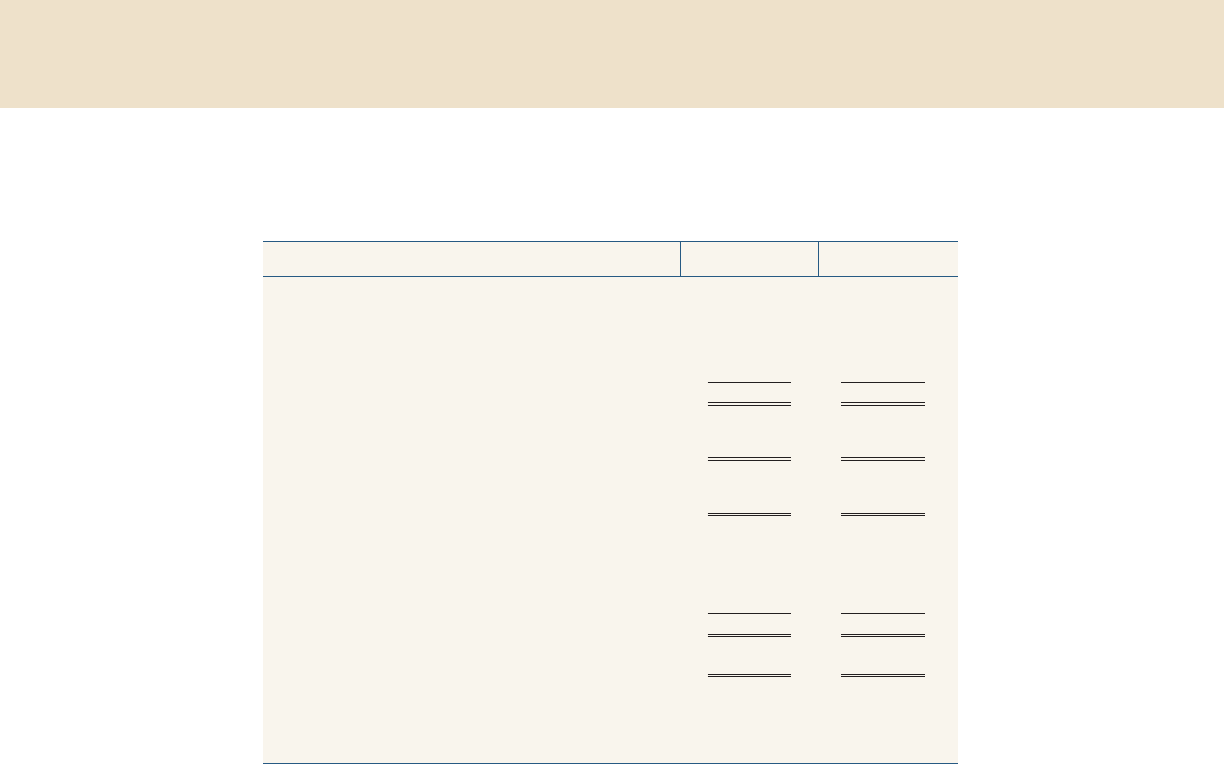

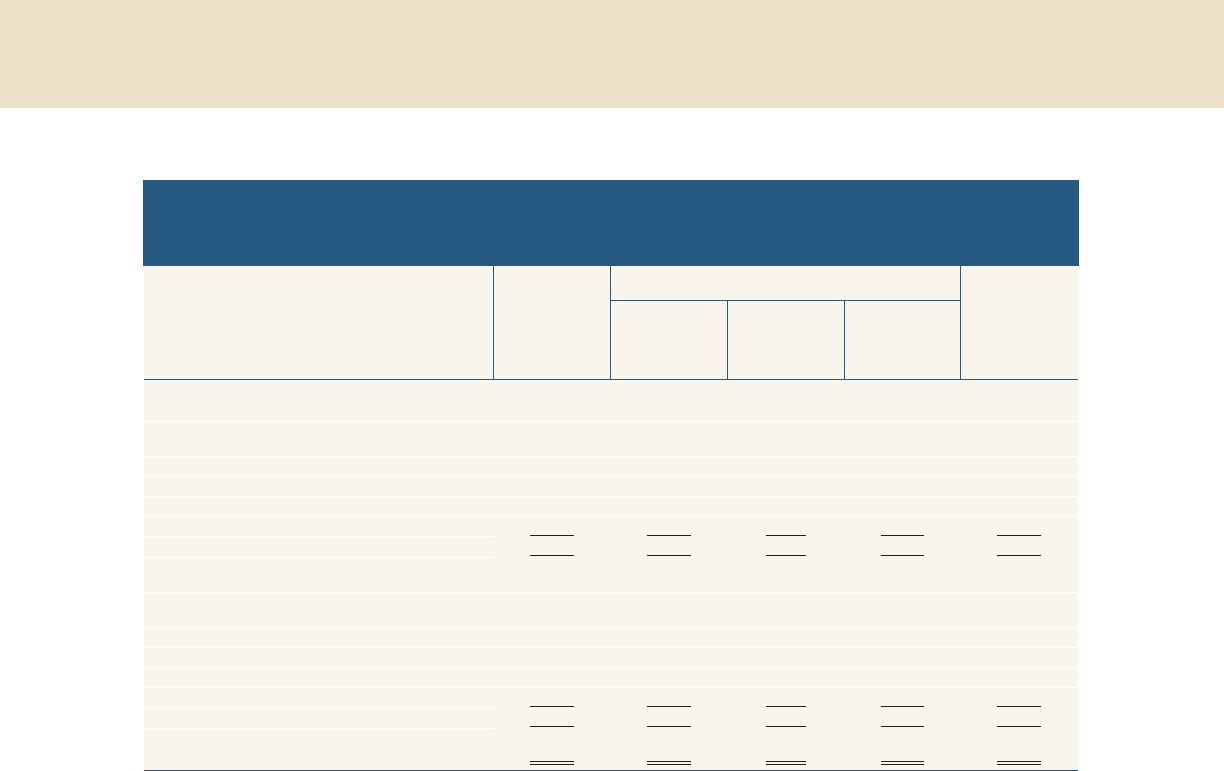

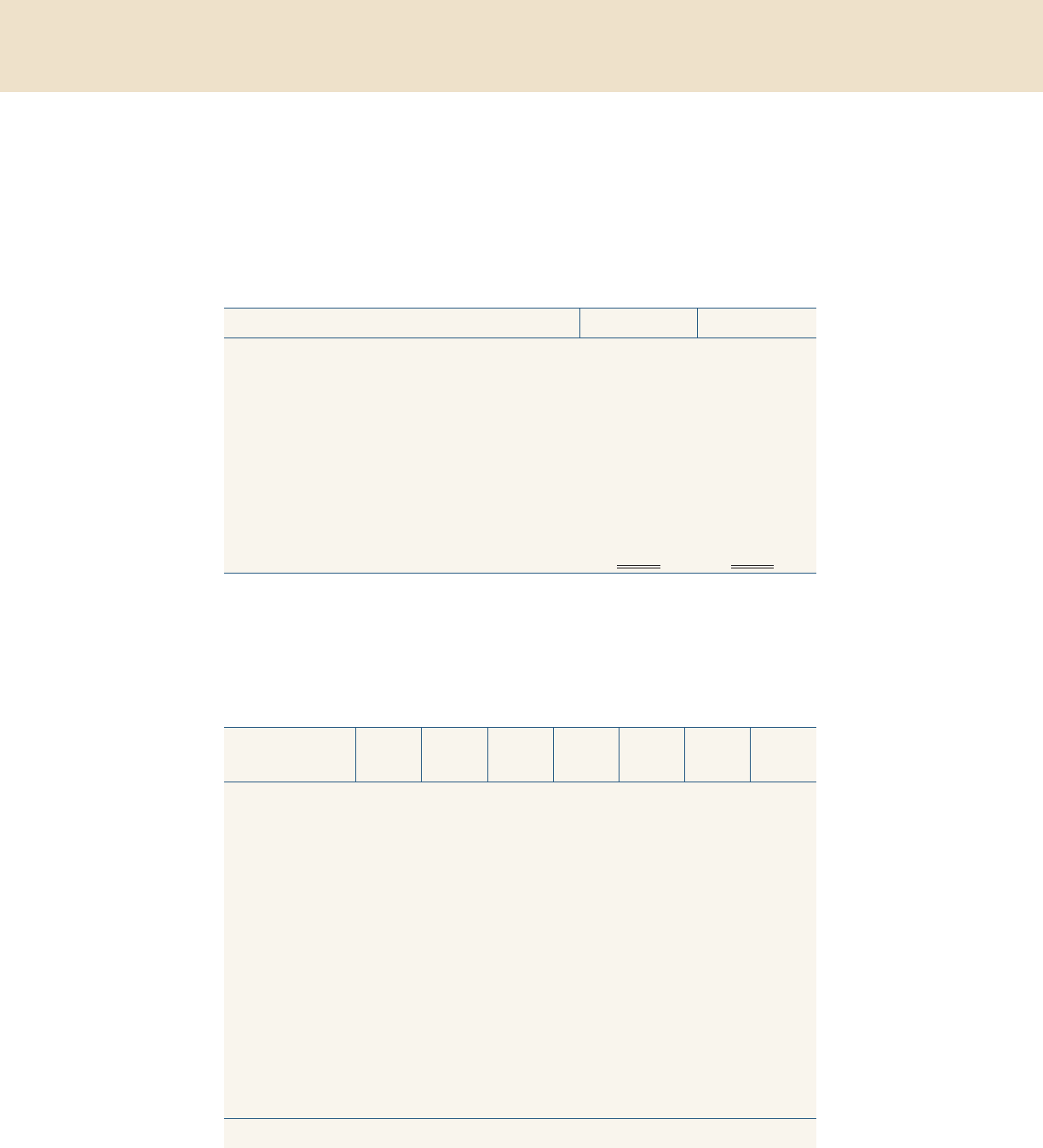

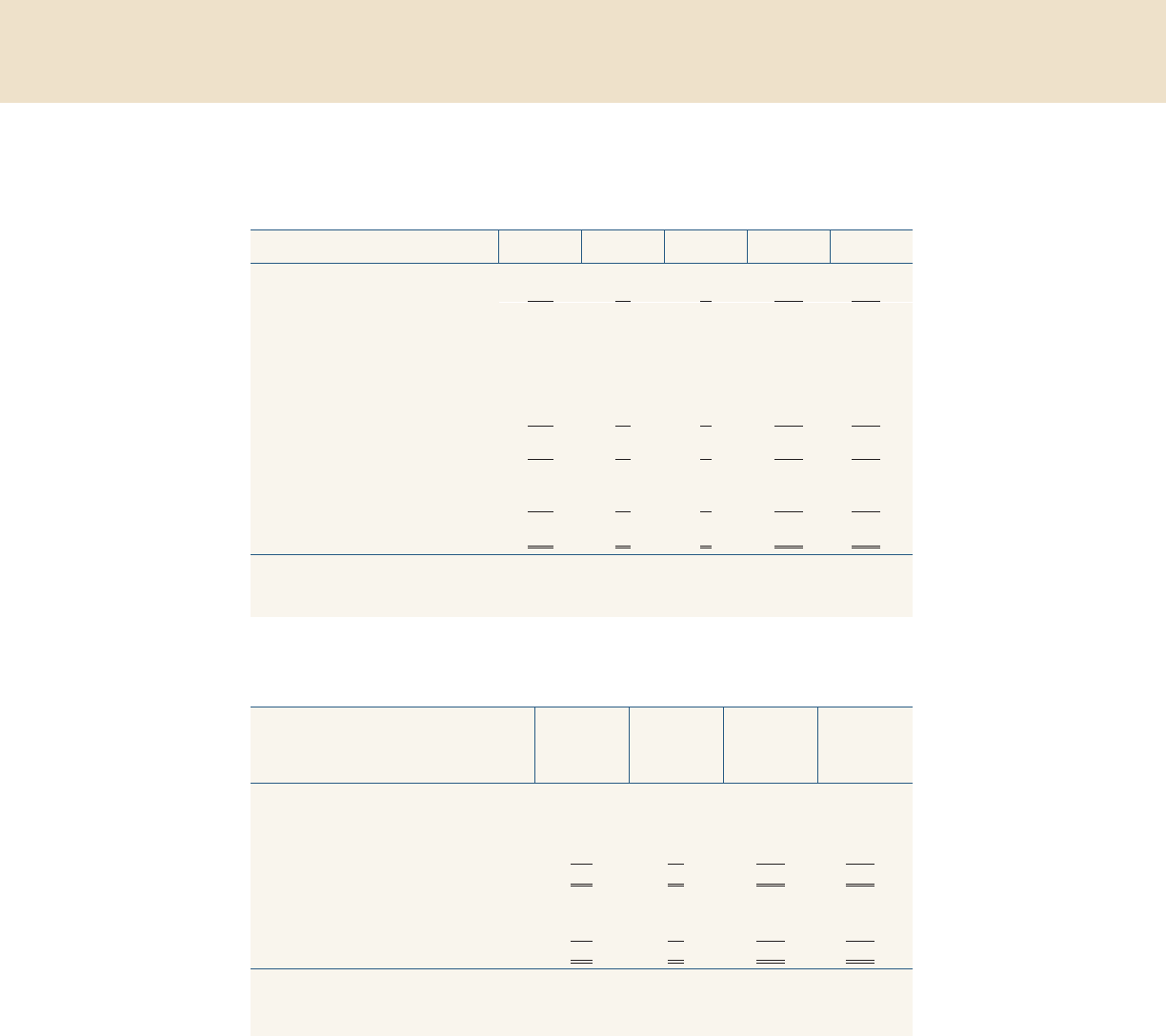

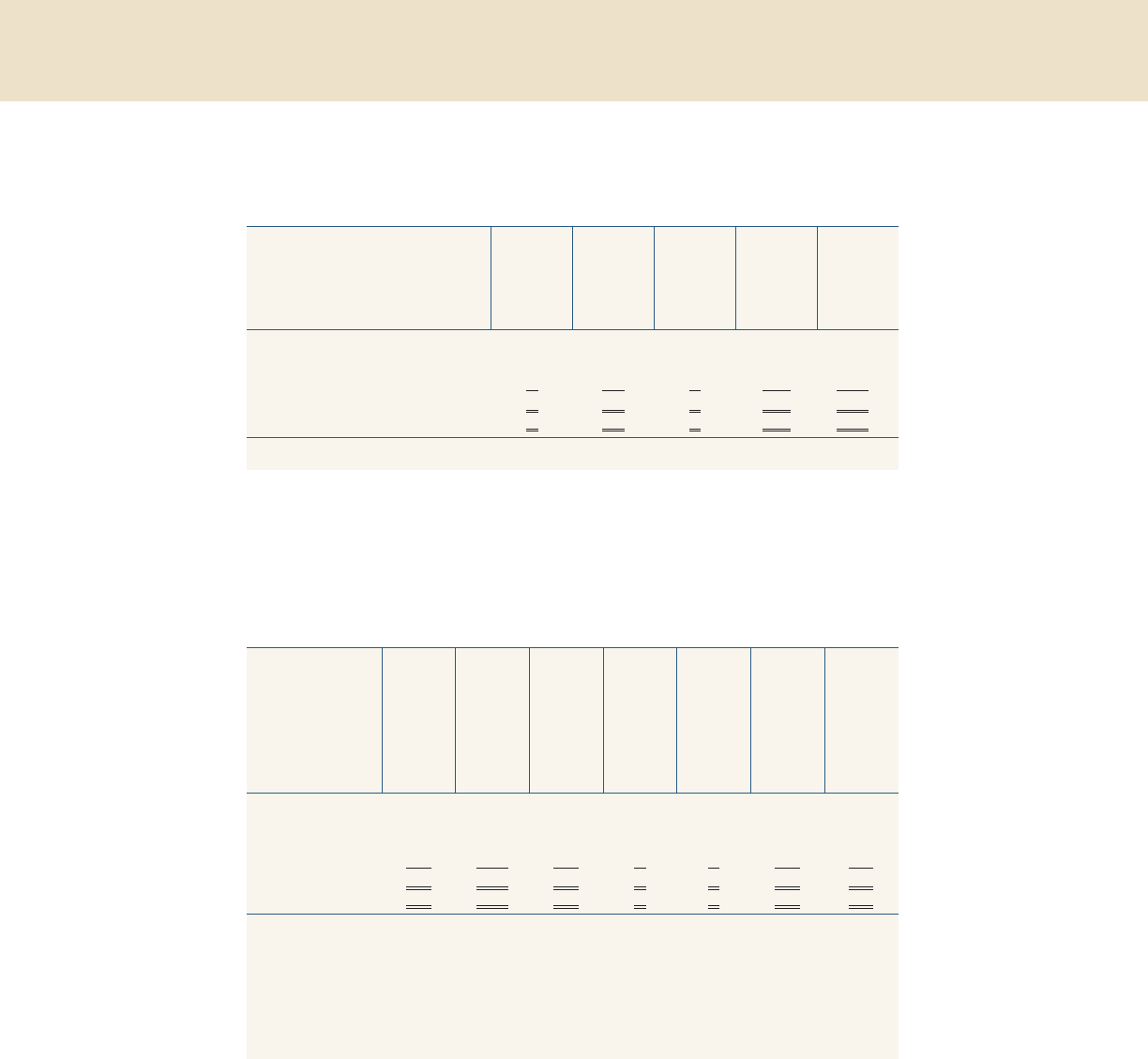

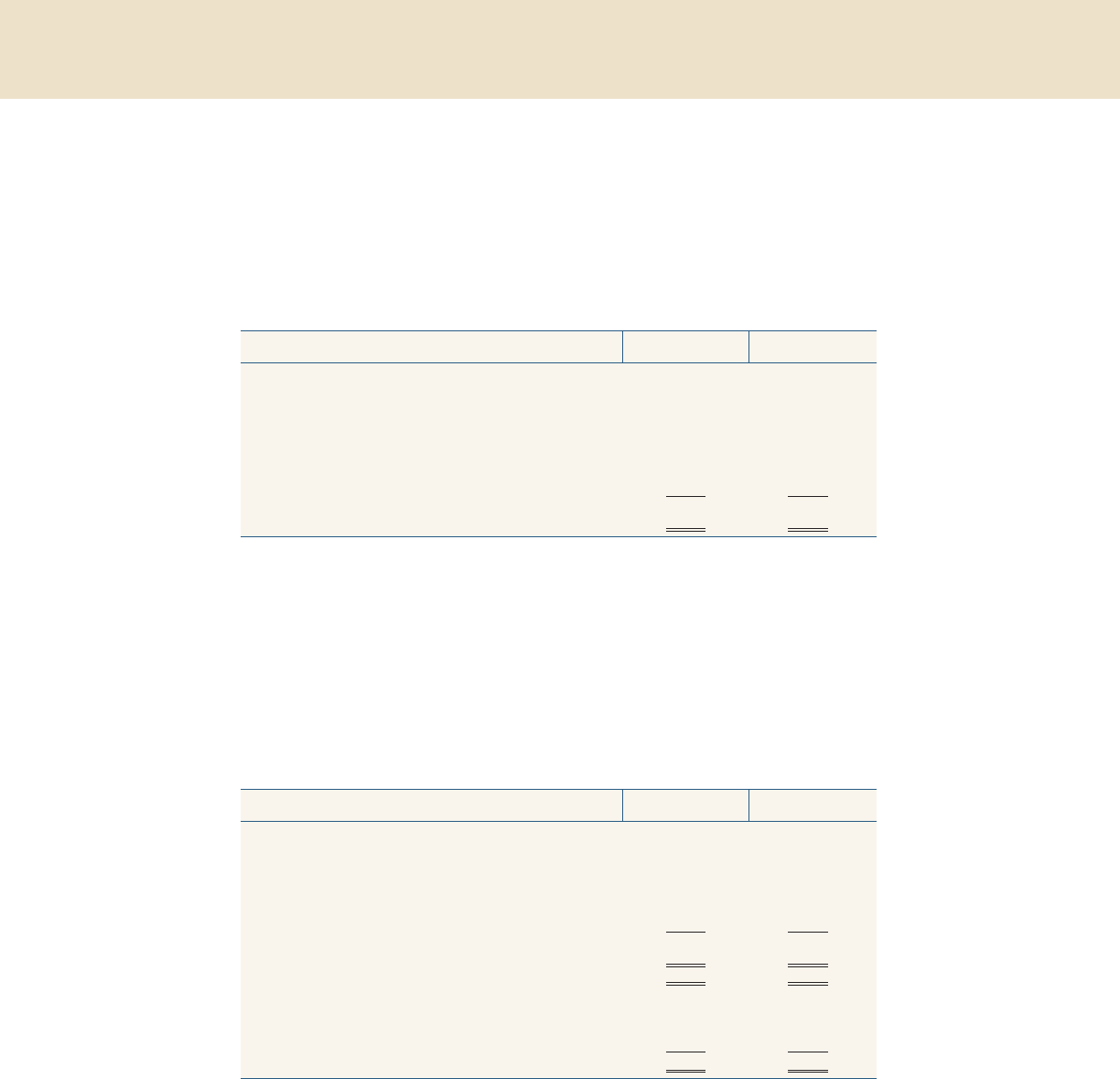

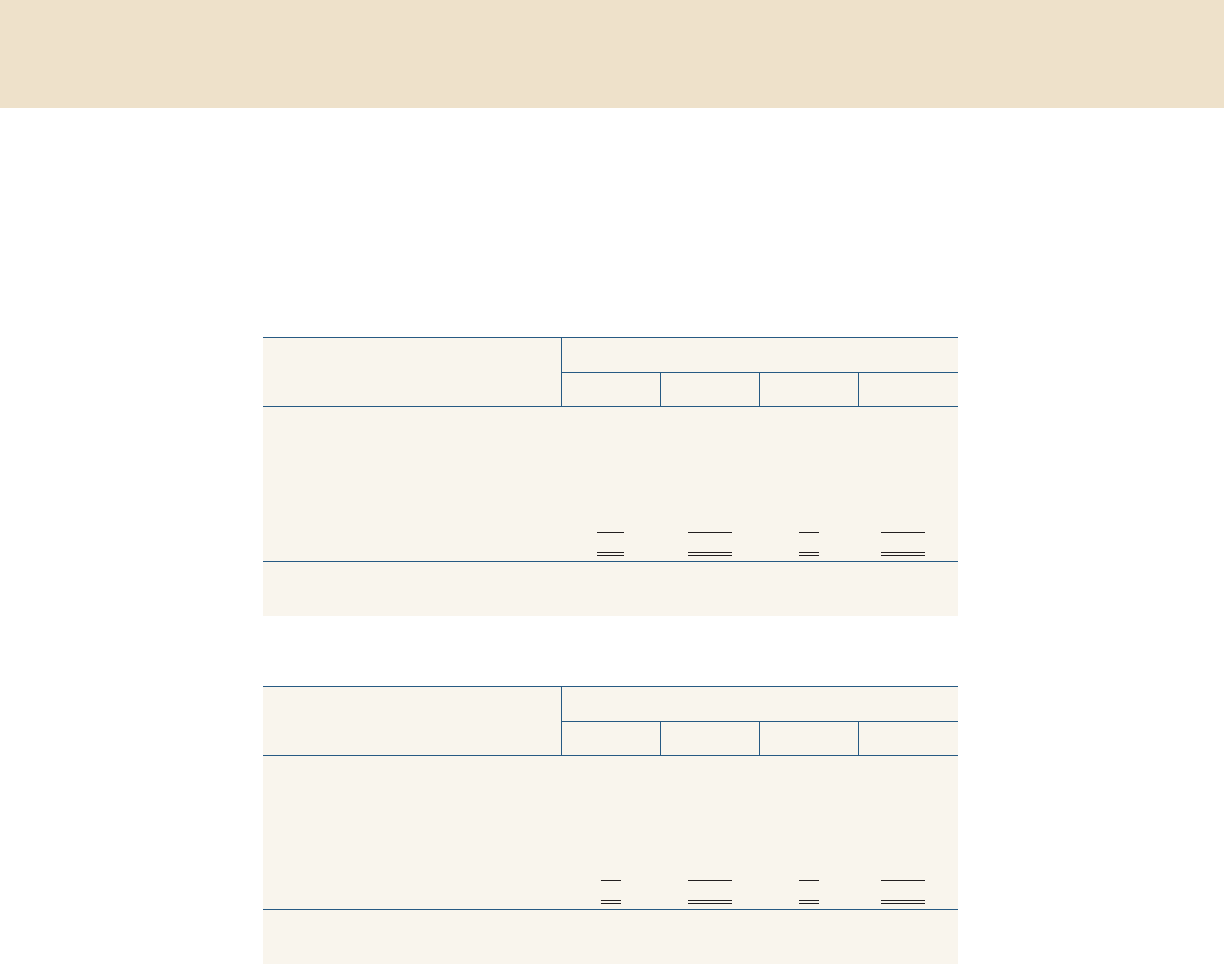

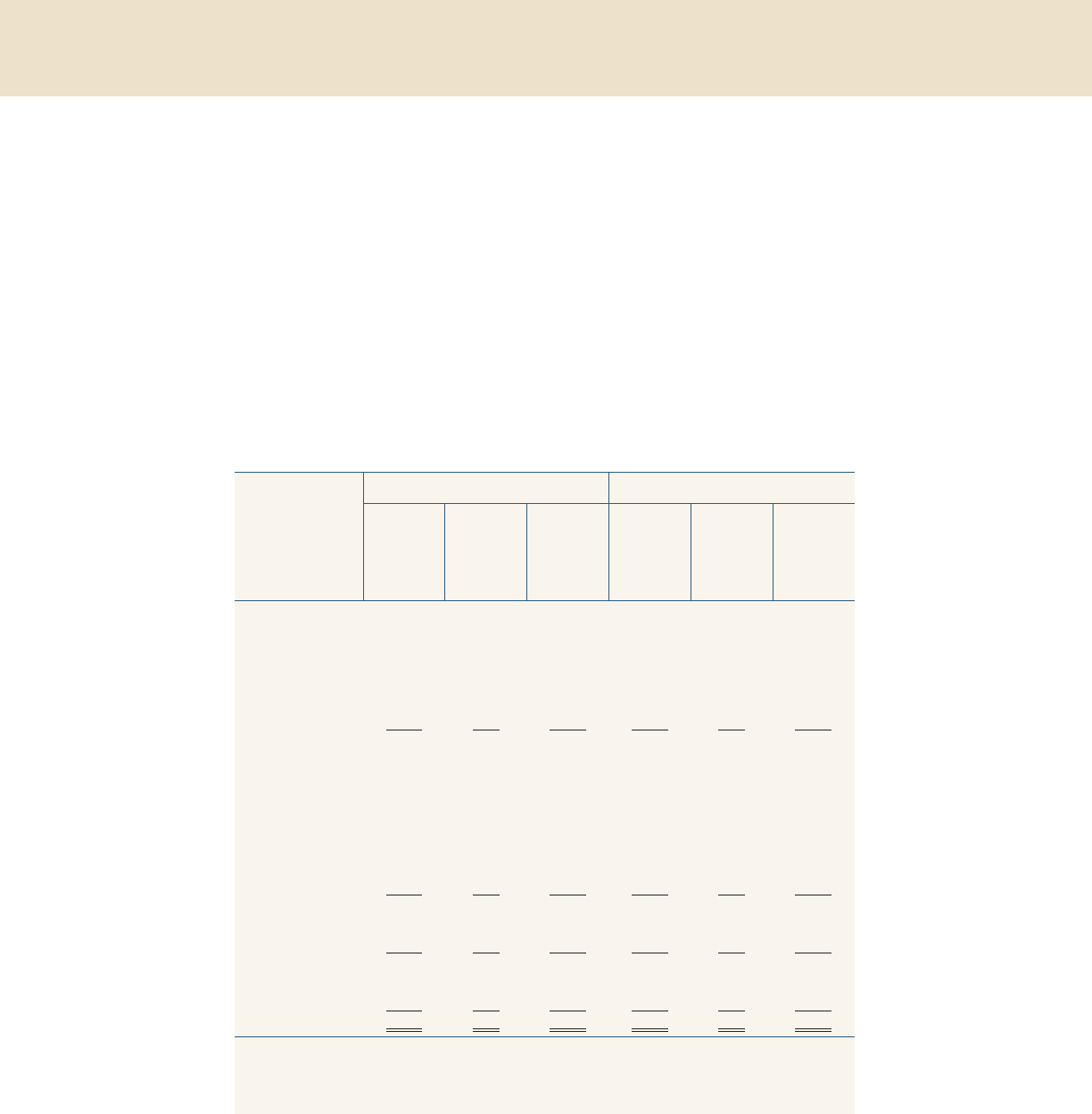

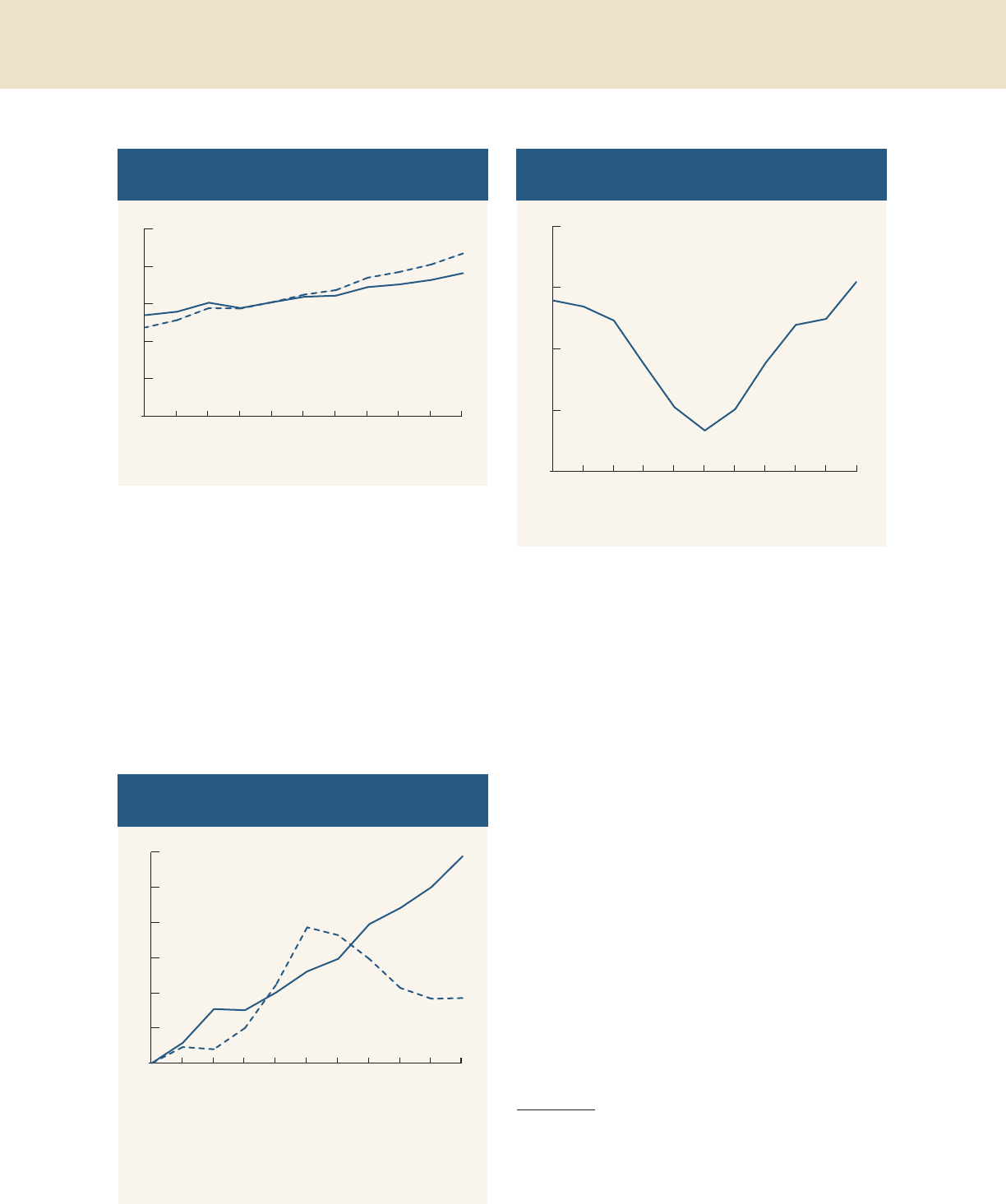

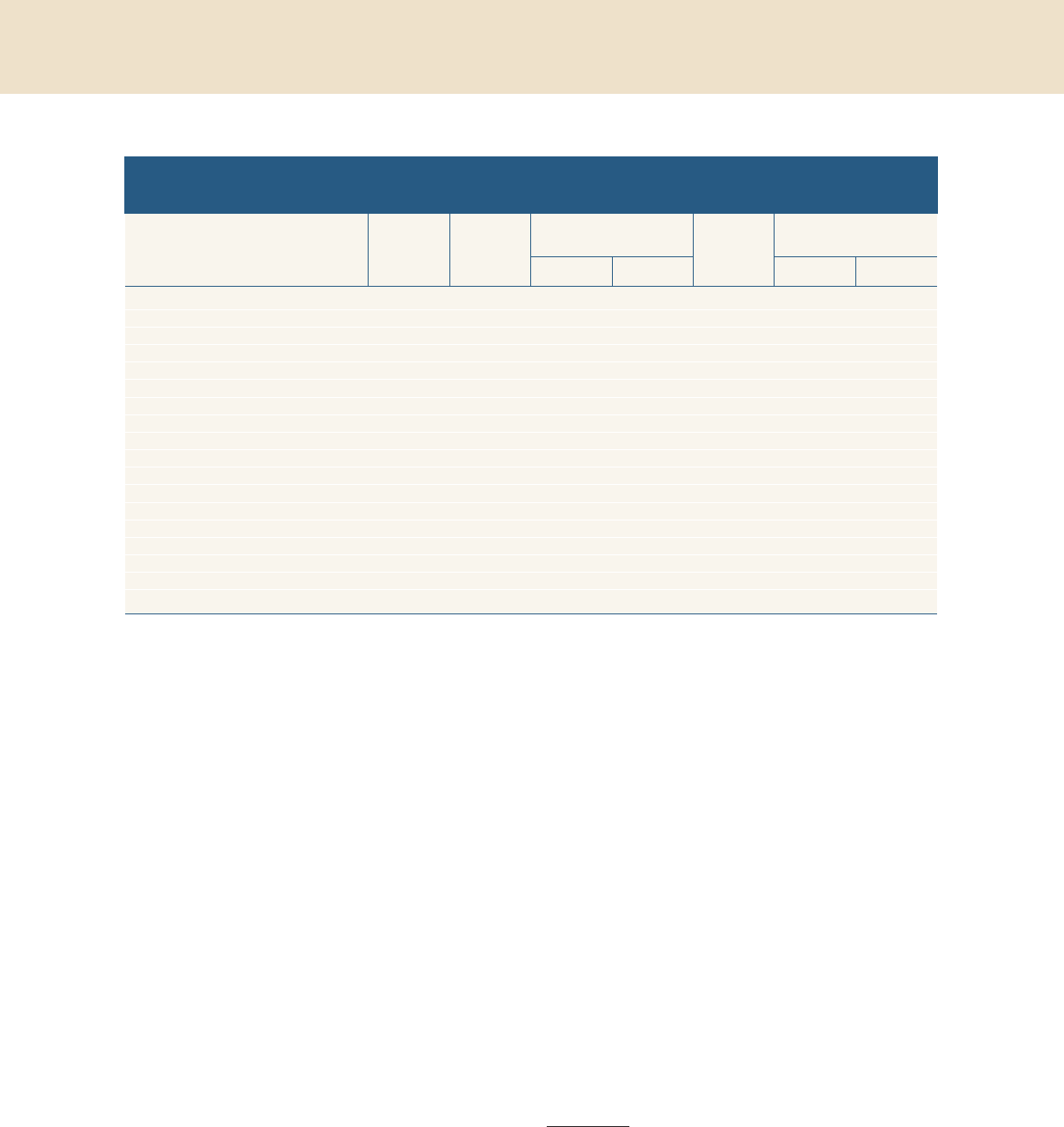

Figure 1. Net change in payroll employment

Total nonfarm

Private

800

600

400

200

+

_

0

200

400

Thousands of jobs

20152014201320122011201020092008

3-month moving averages

Source: Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments 7

employment-to-population ratio climbed noticeably

higher in 2014 and early 2015 after having moved

more or less sideways for much of the recovery. The

quit rate, which is often perceived as a measure of

worker confidence in labor market opportunities, has

largely recovered to its pre-recession level. Moreover,

an index constructed by Federal Reserve Board staff

that aims to summarize movements in a wide array of

labor market indicators also suggests that labor mar-

ket conditions strengthened further in 2014, and that

the gains have been quite strong in recent months.

1

. . . while gains in compensation have been

modest . . .

Even as the labor market has been improving, most

measures of labor compensation have continued to

show only modest gains. The employment cost index

(ECI) for private industry workers, which measures

both wages and the cost of employer-provided ben-

efits, rose 2¼ percent over the 12 months ending in

December, only slightly faster than the gains of

about 2 percent that had prevailed for several years.

Two other prominent measures of compensation—

average hourly earnings and business-sector compen-

sation per hour—increased slightly less than the ECI

over the past year and have shown fewer signs of

acceleration. Over the past five years, the gains in all

three of these measures of nominal compensation

have fallen well short of their pre-recession averages

and have only slightly outpaced inflation. That said,

the drop in energy prices has pushed up real wages in

recent months.

. . . and productivity growth has been lackluster

Over time, increases in productivity are the central

determinant of improvements in living standards.

Labor productivity in the private business sector has

increased at an average annual pace of 1¼ percent

since the recession began in late 2007. This pace is

close to the average that prevailed between the mid-

1970s and the mid-1990s, but it is well below the pace

of the earlier post–World War II period and the

period from the mid-1990s to the eve of the financial

crisis. In recent years, productivity growth has been

1

For details on the construction of the labor market conditions

index, see Hess Chung, Bruce Fallick, Christopher Nekarda,

and David Ratner (2014), “Assessing the Change in Labor Mar-

ket Conditions,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series

2014-109 (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, December),

www.federalreserve.gov/

econresdata/feds/2014/files/2014109pap.pdf

.

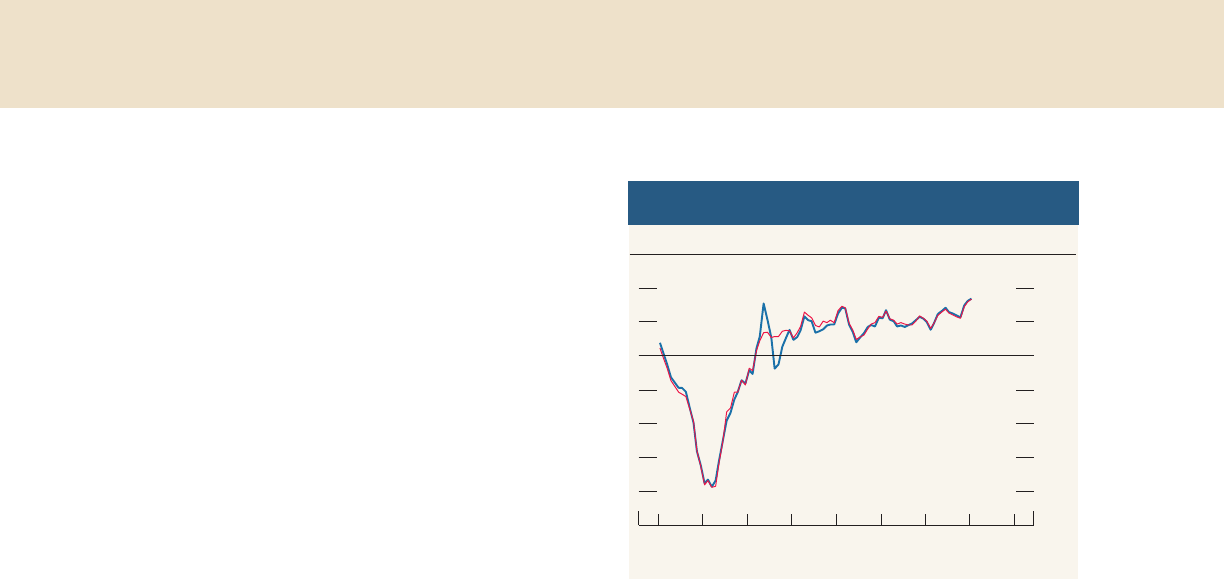

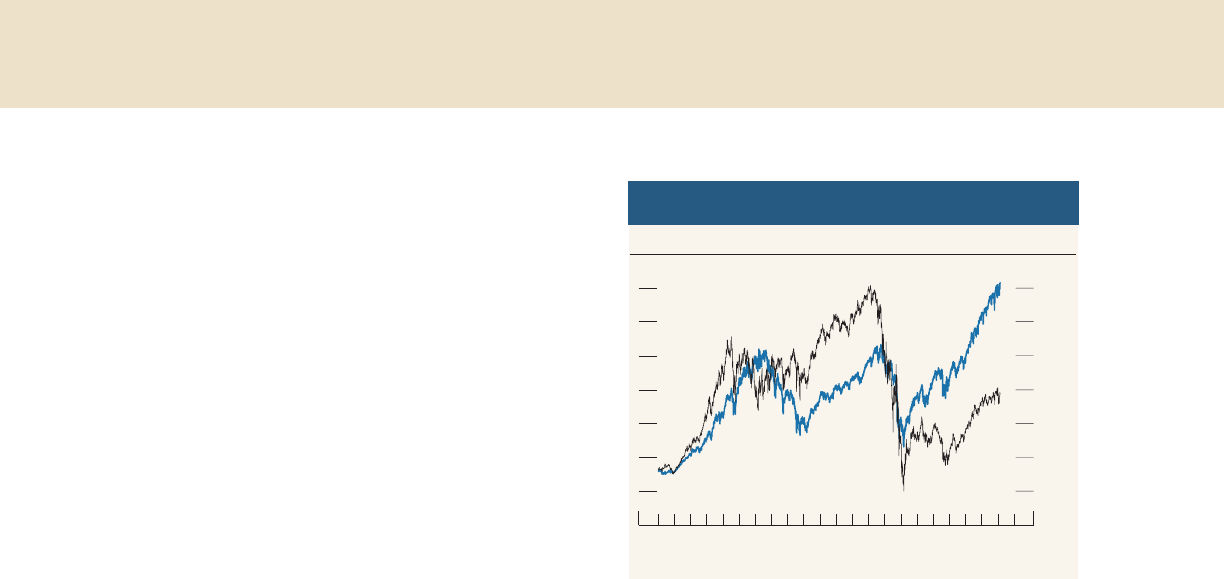

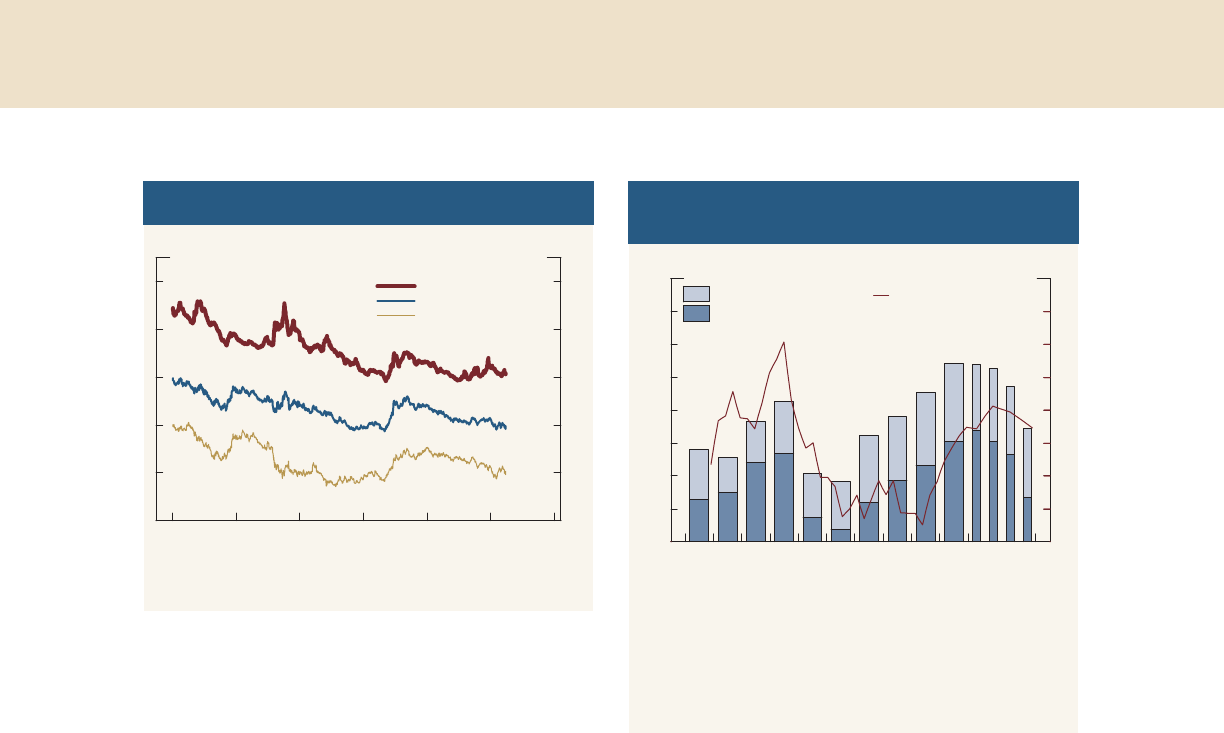

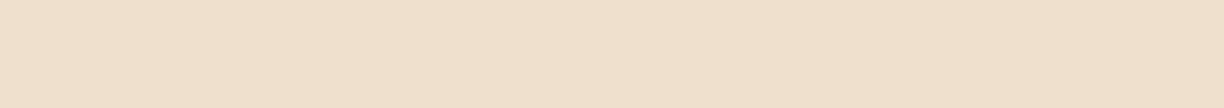

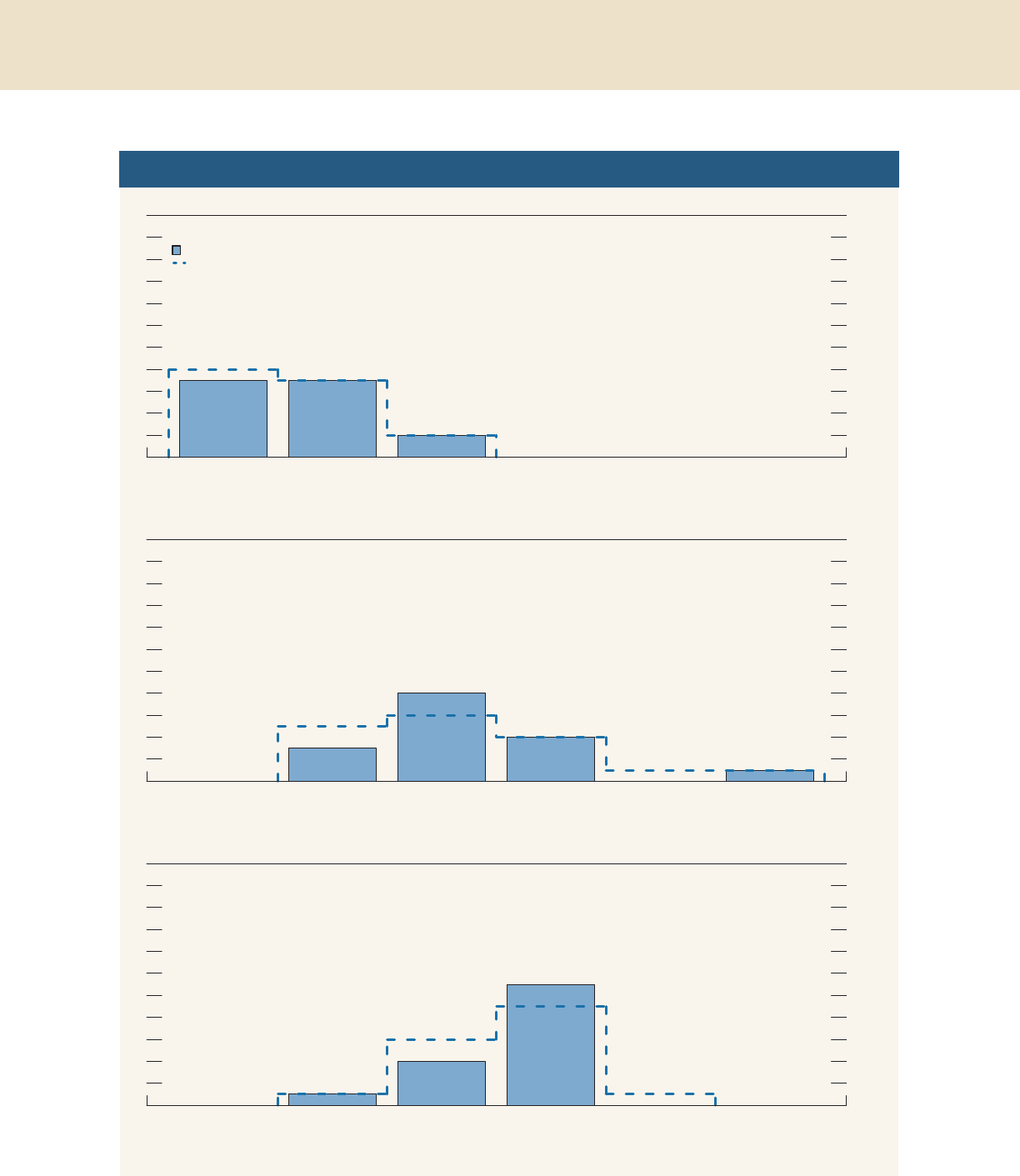

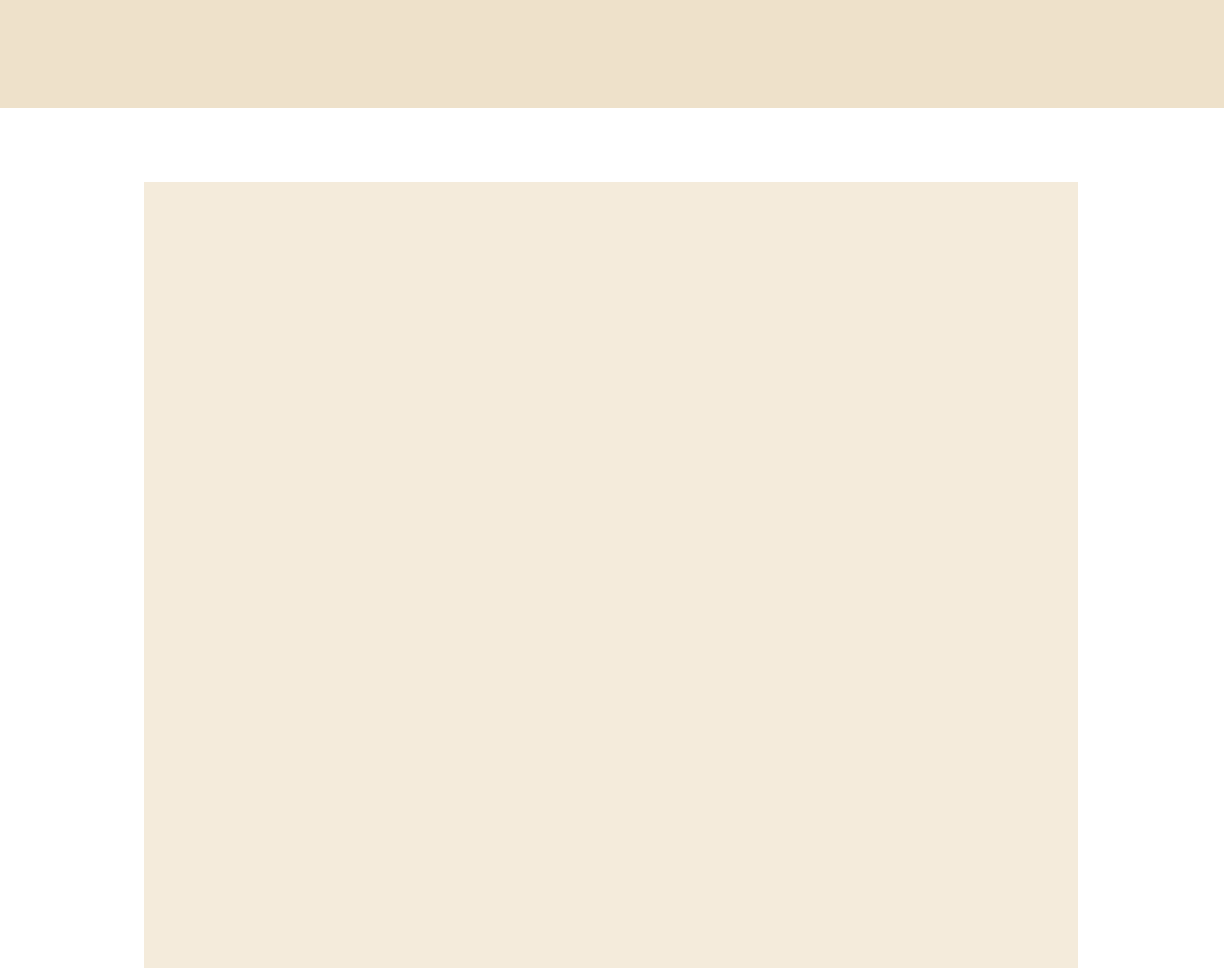

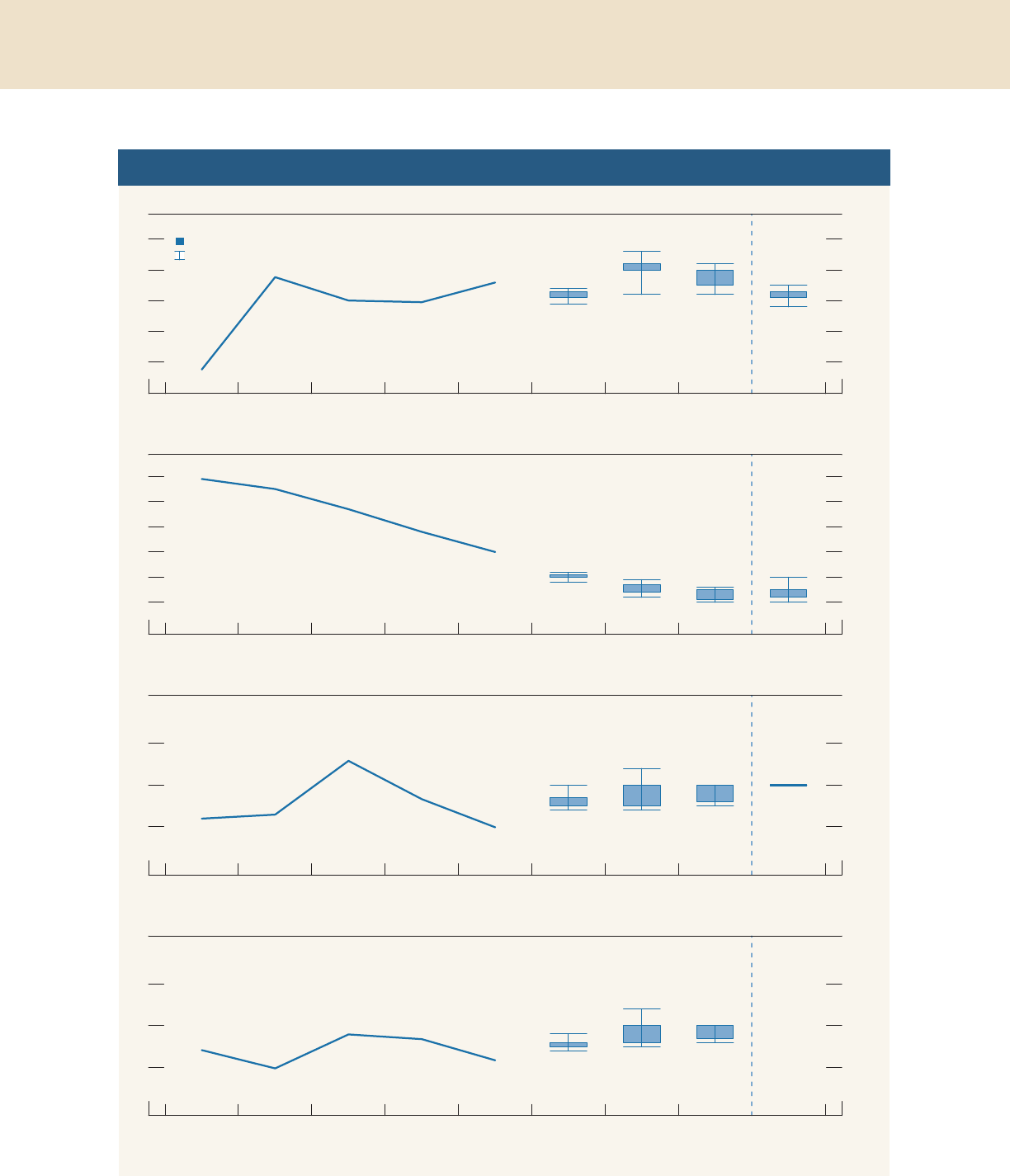

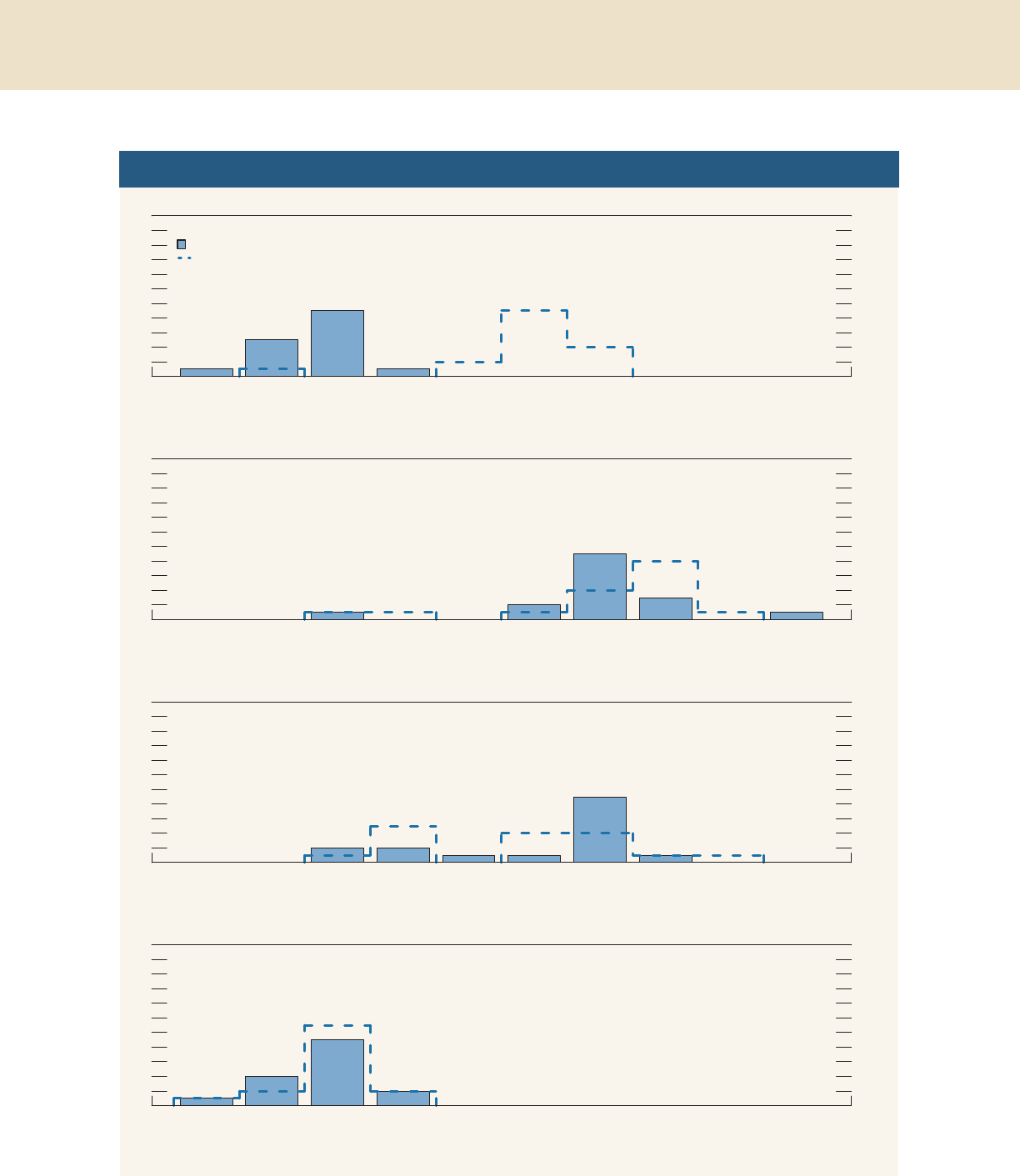

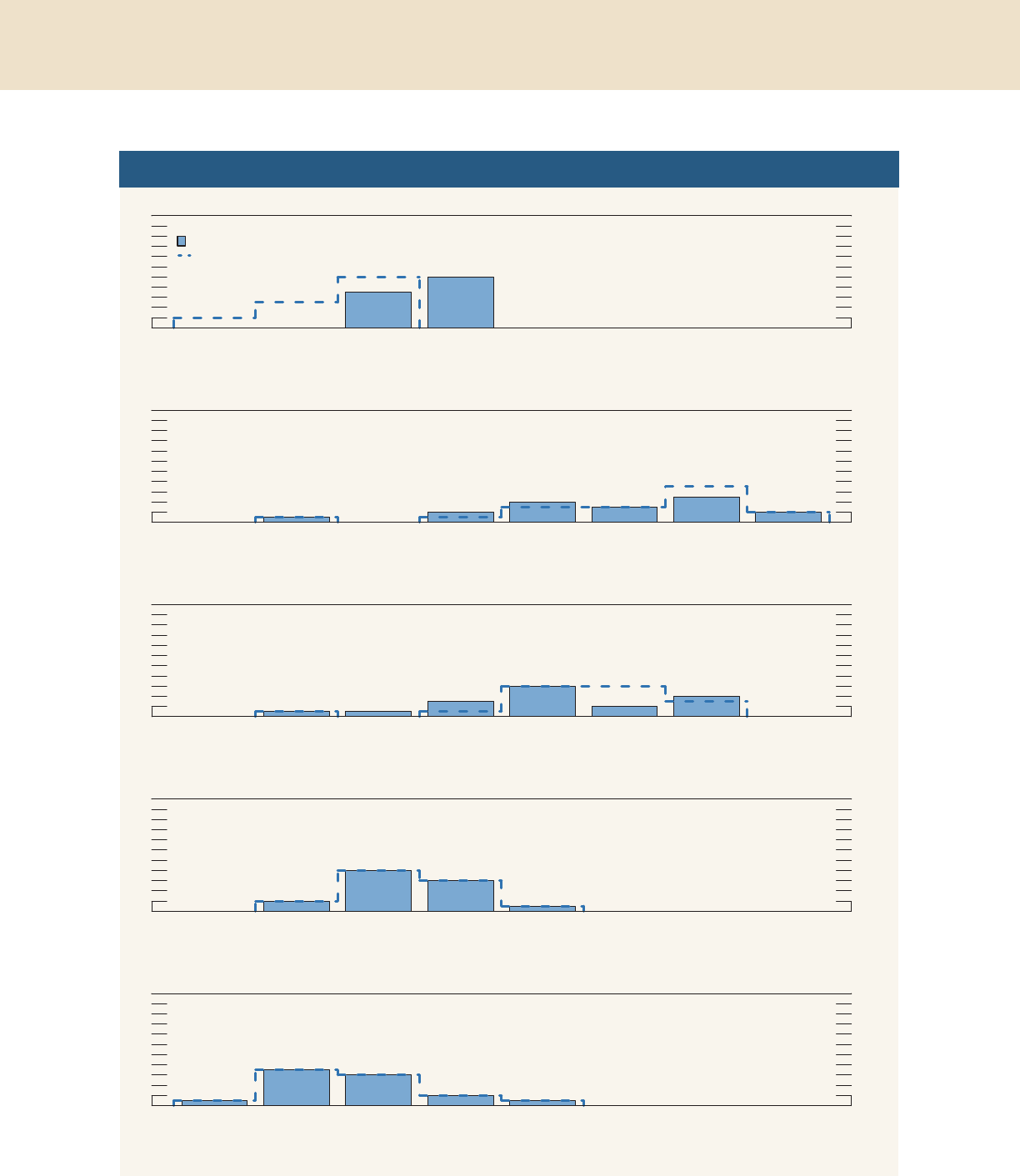

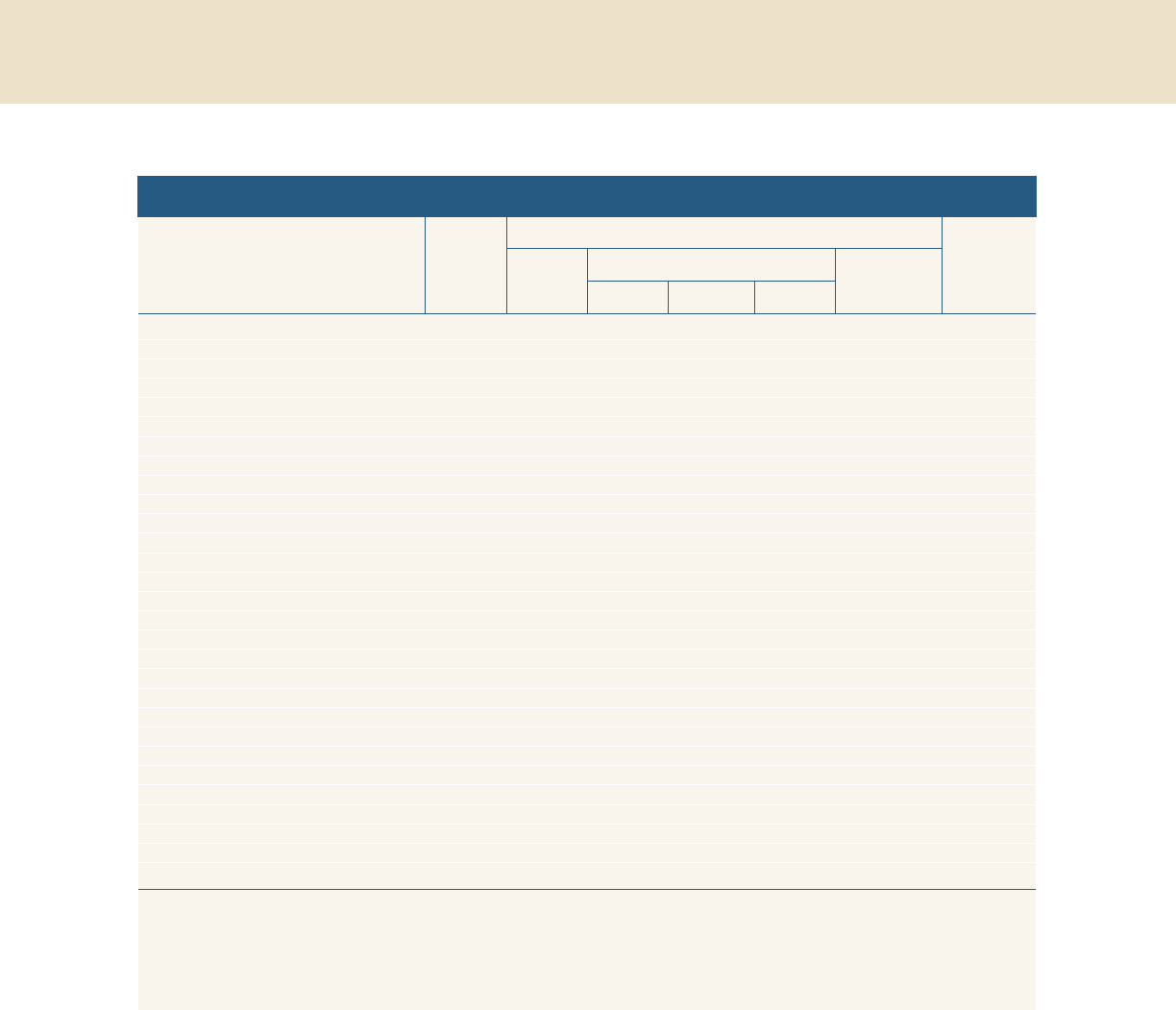

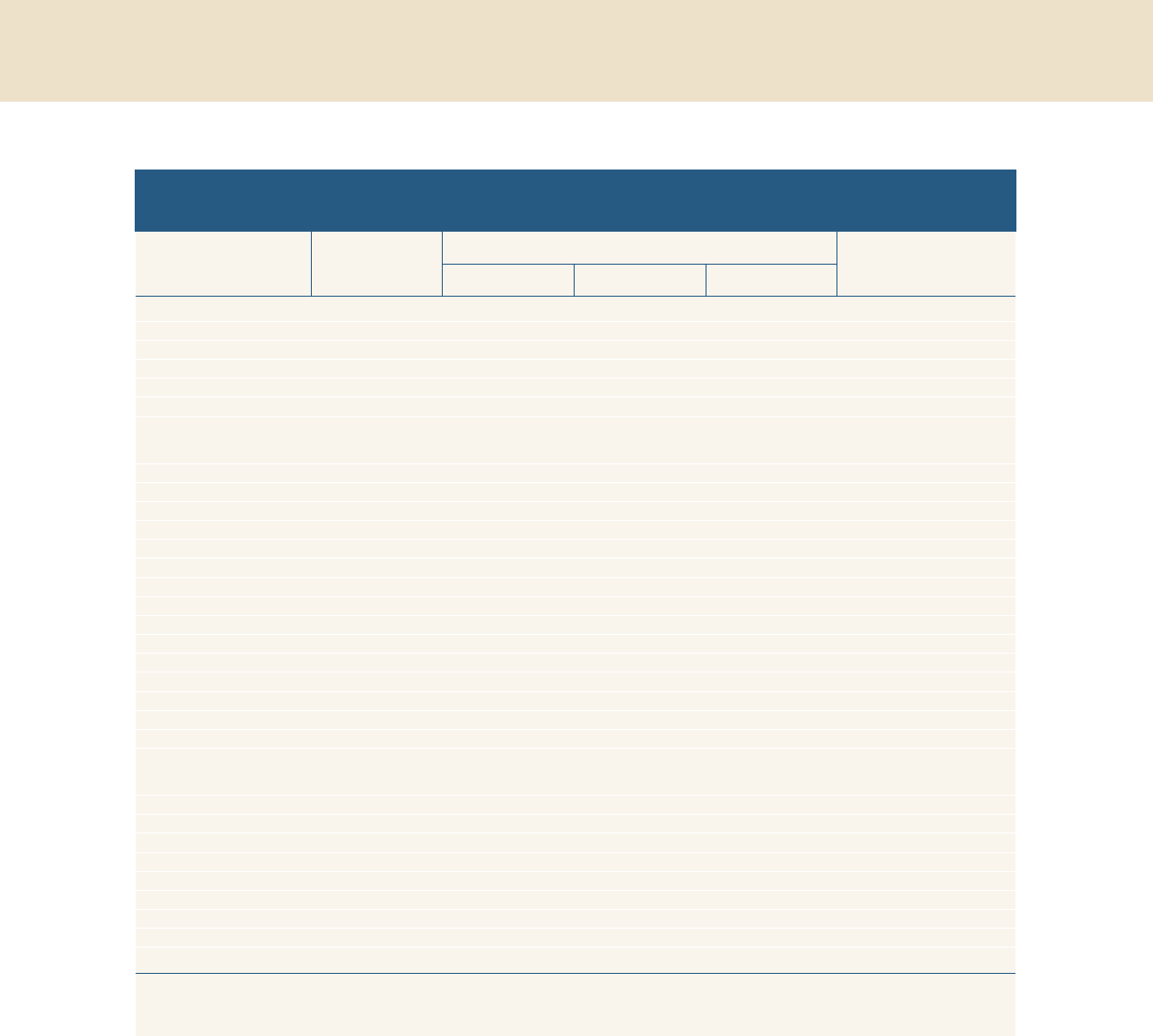

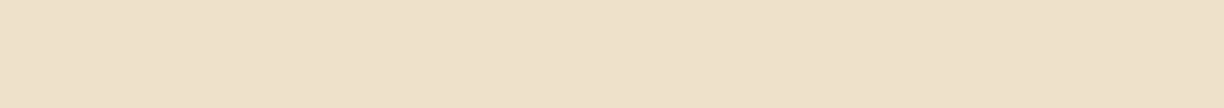

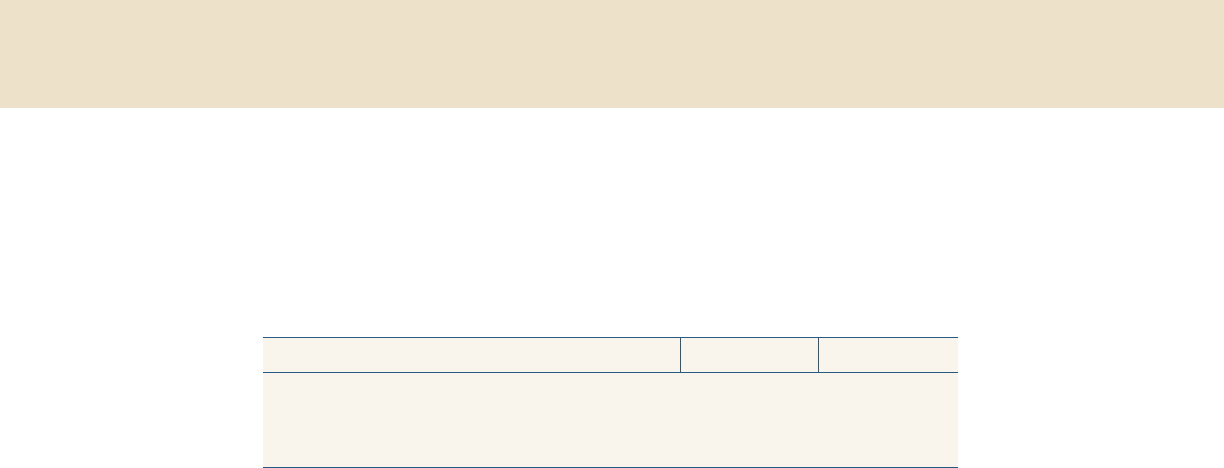

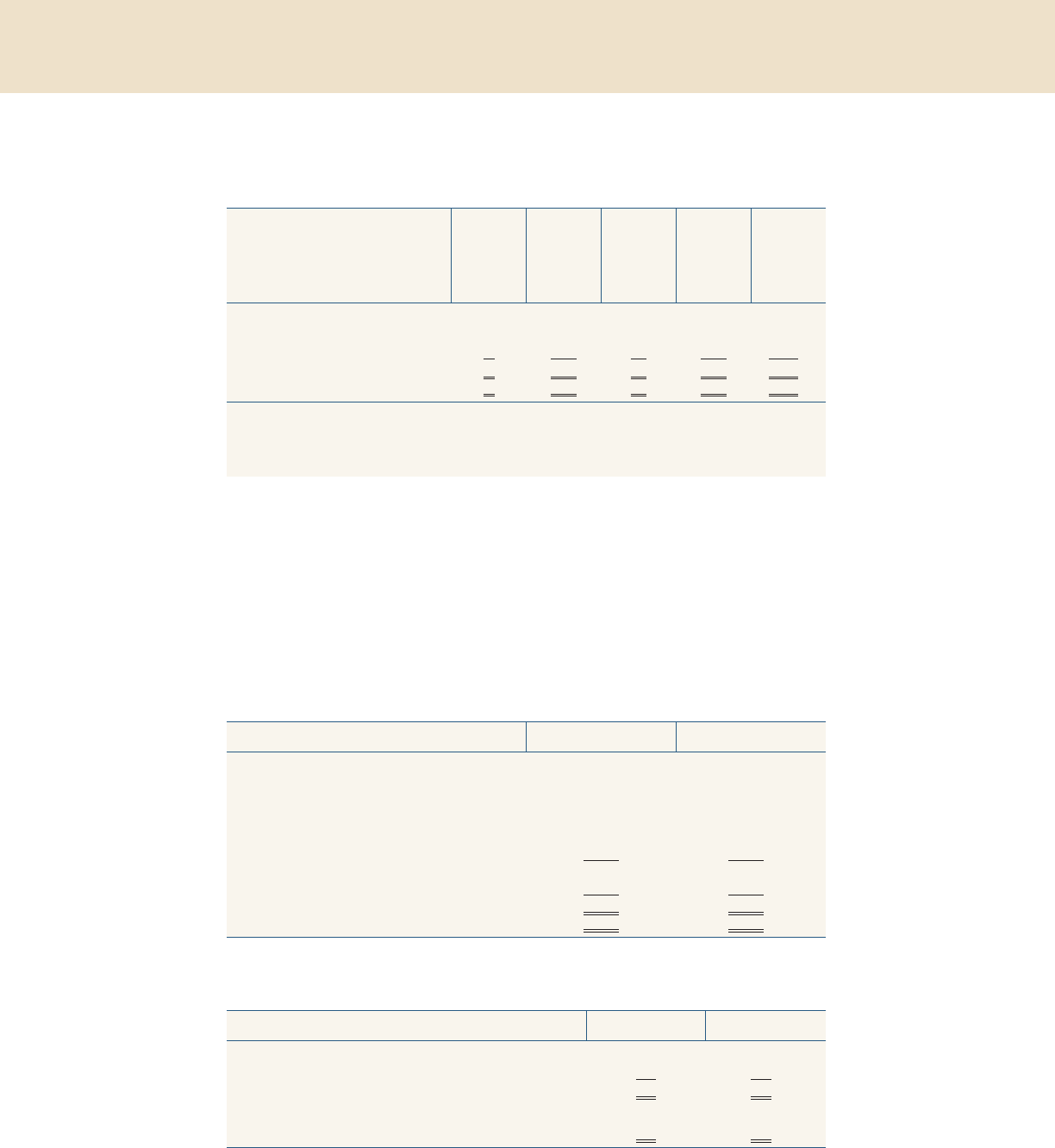

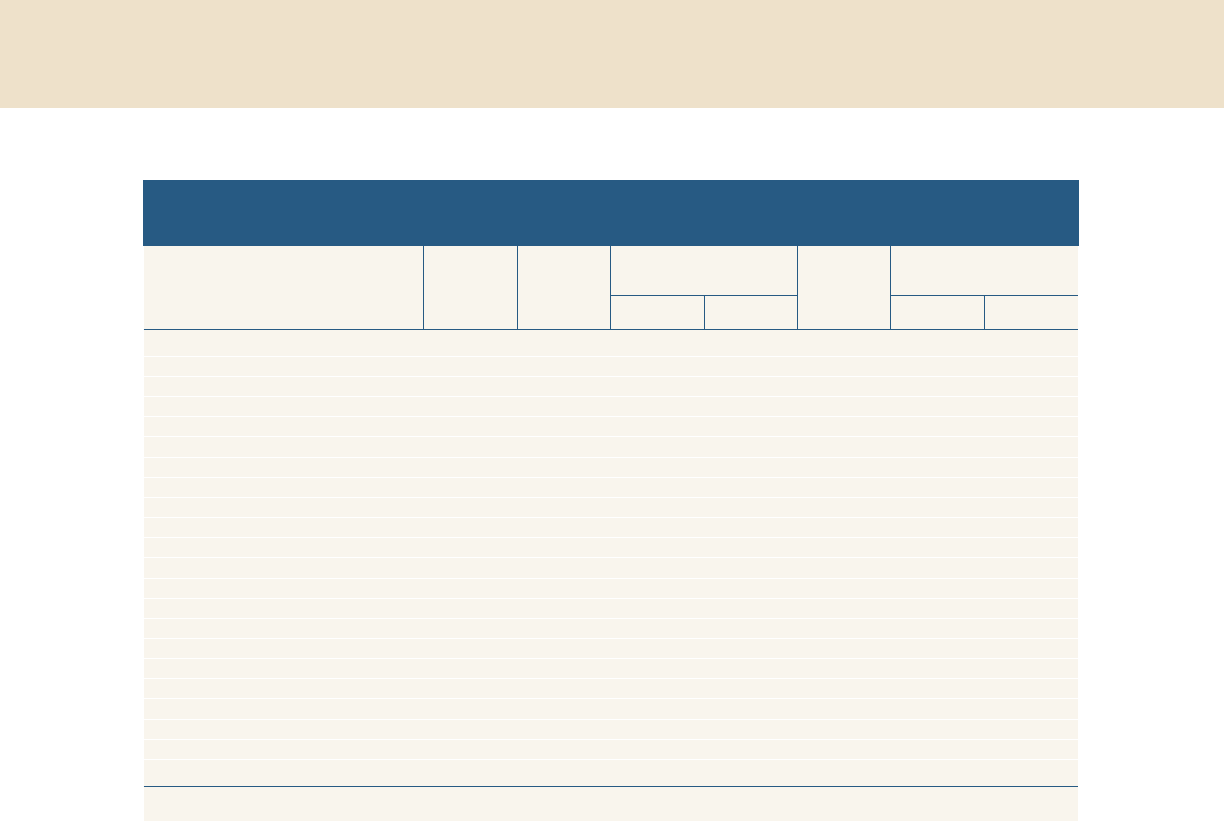

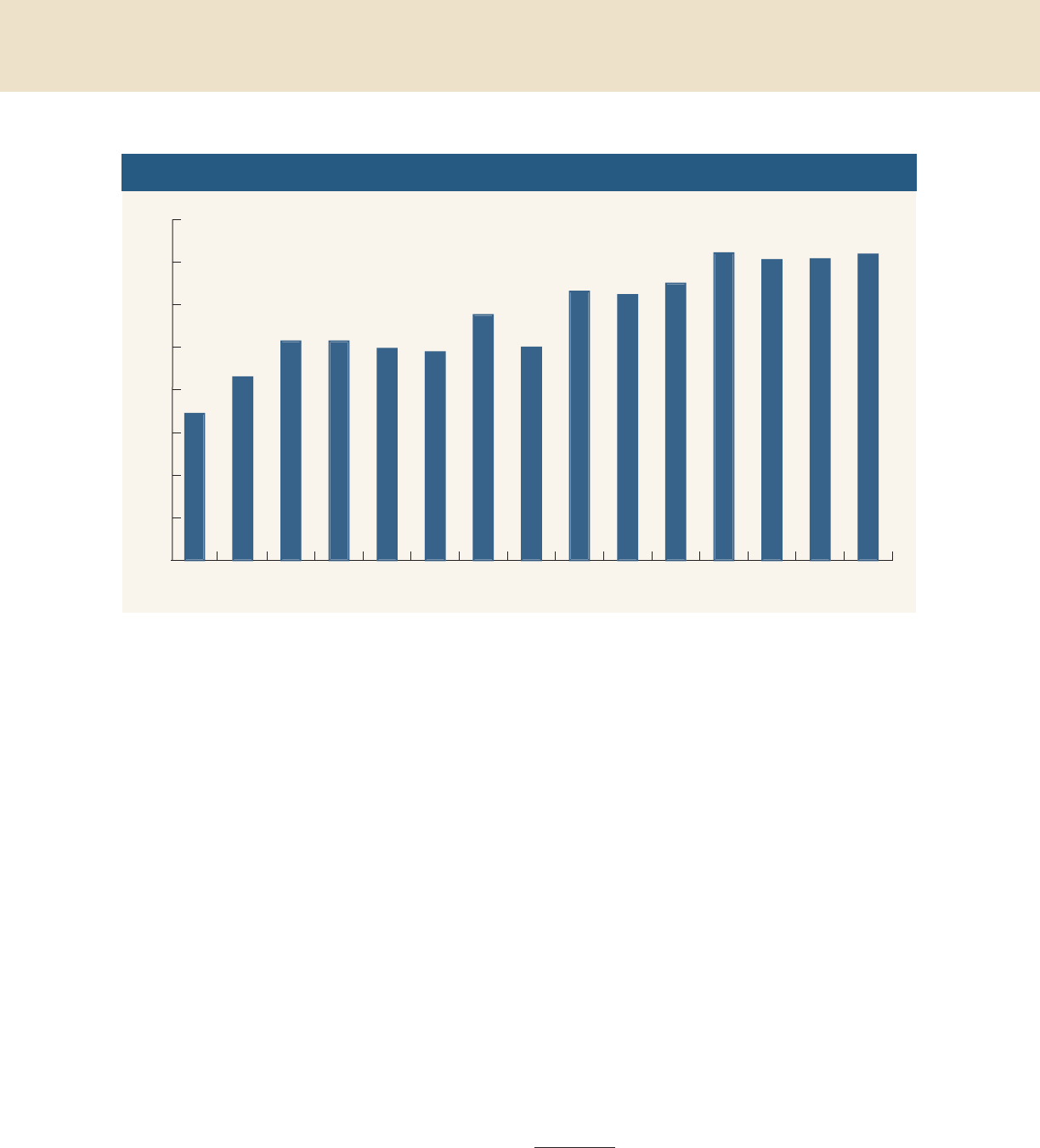

Figure 2. Measures of labor underutilization

U-5

U-4

U-6

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Percent

2015201320112009200720052003

Monthly

Unemployment rate

Note: U-4 measures total unemployed plus discouraged workers, as a percent of the labor force plus discouraged workers. Discouraged workers are a subset of marginally

attached workers who are not currently looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them. U-5 measures total unemployed plus all marginally attached to the

labor force, as a percent of the labor force plus persons marginally attached to the labor force. Marginally attached workers are not in the labor force, want and are available for

work, and have looked for a job in the past 12 months. U-6 measures total unemployed plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic rea-

sons, as a percent of the labor force plus all marginally attached workers. The shaded bar indicates a period of business recession as defined by the National Bureau of Eco-

nomic Research.

Source: Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

8 101st Annual Report | 2014

held down by, among other factors, the sharp drop in

businesses’ capital expenditures over the recession

and the moderate recovery in expenditures since

then. Productivity gains may be better supported in

the future as investment continues to strengthen.

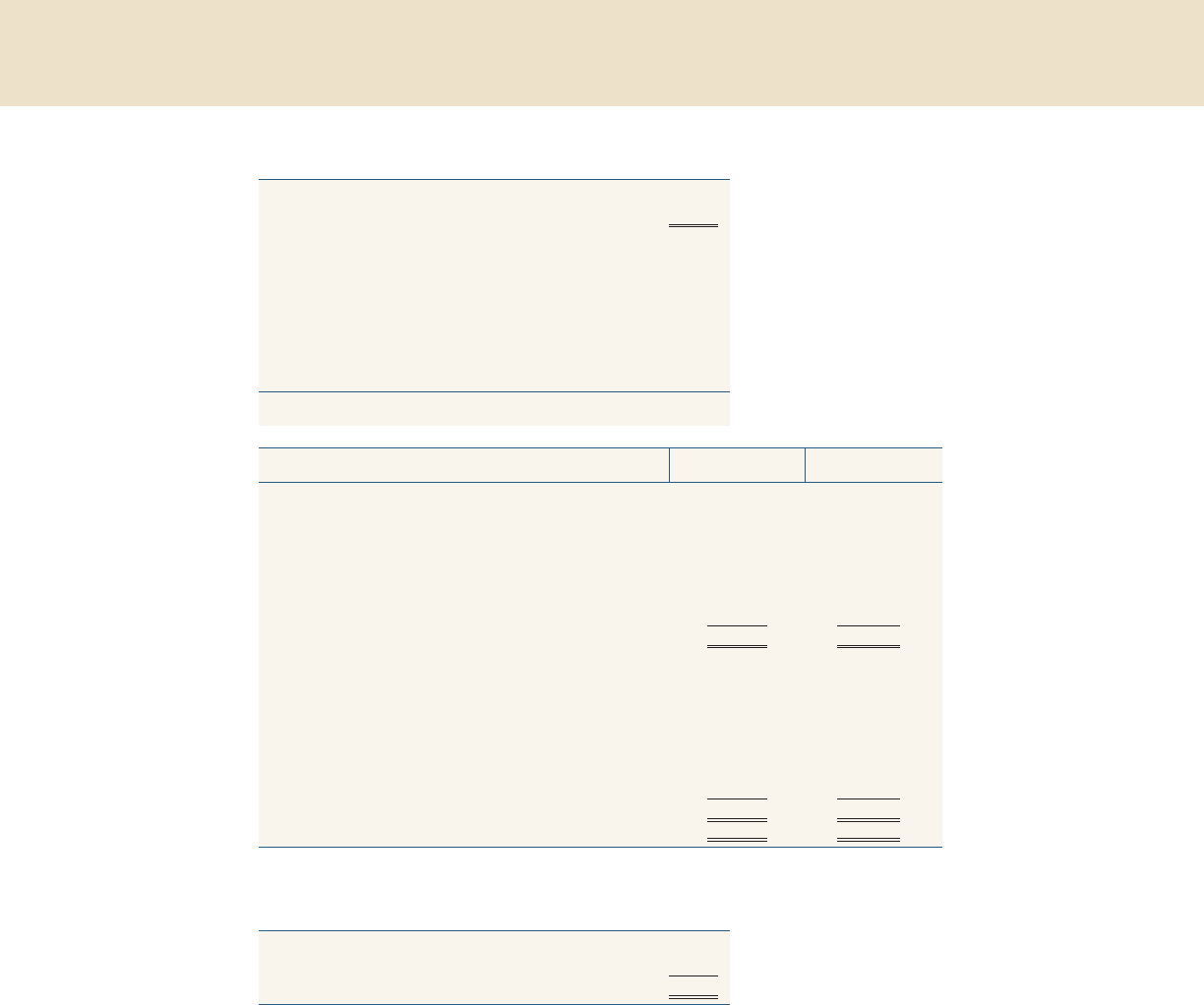

A plunge in crude oil prices has held down

consumer prices . . .

As discussed in the box “

The Effect of the Recent

Decline in Oil Prices on Economic Activity

” on pages

8–9 of the February 2015 Monetary Policy Report,

crude oil prices have plummeted since June 2014 (

fig-

ure 3

). This sharp drop has caused overall consumer

price inflation to slow, mainly due to falling gasoline

prices: The national average of retail gasoline prices

moved down from about $3.75 per gallon in June to

about $2.20 per gallon in January. Crude oil prices

have turned slightly higher in recent weeks, and

futures markets suggest that prices are expected to

edge up further in coming years; nevertheless, oil

prices are still expected to remain well below the lev-

els that had prevailed through last June.

Over the past six months, increases in food prices

have moderated. Consumer food price increases had

been somewhat elevated in early 2014 as a result of

rising food commodity prices, but those commodity

prices have since eased, and increases at the retail

level have slowed accordingly.

. . . but even outside of the energy and food

categories, inflation has remained subdued

Inflation for items other than food and energy (so-

called core inflation) remains modest. Core PCE

prices rose at an annual rate of only about 1 percent

over the last six months of 2014 after having risen at

a 1¾ percent rate in the first half of the year; for

2014 as a whole, core PCE prices were up a little

more than 1¼ percent (

figure 4). The trimmed mean

PCE price index, an alternative indicator of underly-

ing inflation constructed by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Dallas, also increased more slowly in the sec-

ond half of last year. Falling import prices likely held

down core inflation in the second half of the year;

lower oil prices, and easing prices for commodities

more generally, may have played a role as well. In

addition, ongoing resource slack has reinforced the

low-inflation environment, though with the improv-

ing economy, downward pressure from this factor is

likely waning.

Looking at the overall basket of items that people

consume, price increases remain muted and below

the FOMC’s longer-run objective of 2 percent. In

December, the PCE price index was only ¾ percent

above its level from a year earlier. With retail surveys

showing a further sharp decline in gasoline prices in

January, overall consumer prices likely moved lower

early this year.

Survey-based measures of longer-term inflation

expectations have remained stable, while

market-based measures of inflation

compensation have declined

The Federal Reserve tracks indicators of inflation

expectations because such expectations likely factor

into wage- and price-setting decisions and so influ-

ence actual inflation. Survey-based measures of

longer-term inflation expectations, including surveys

of both households and professional forecasters, have

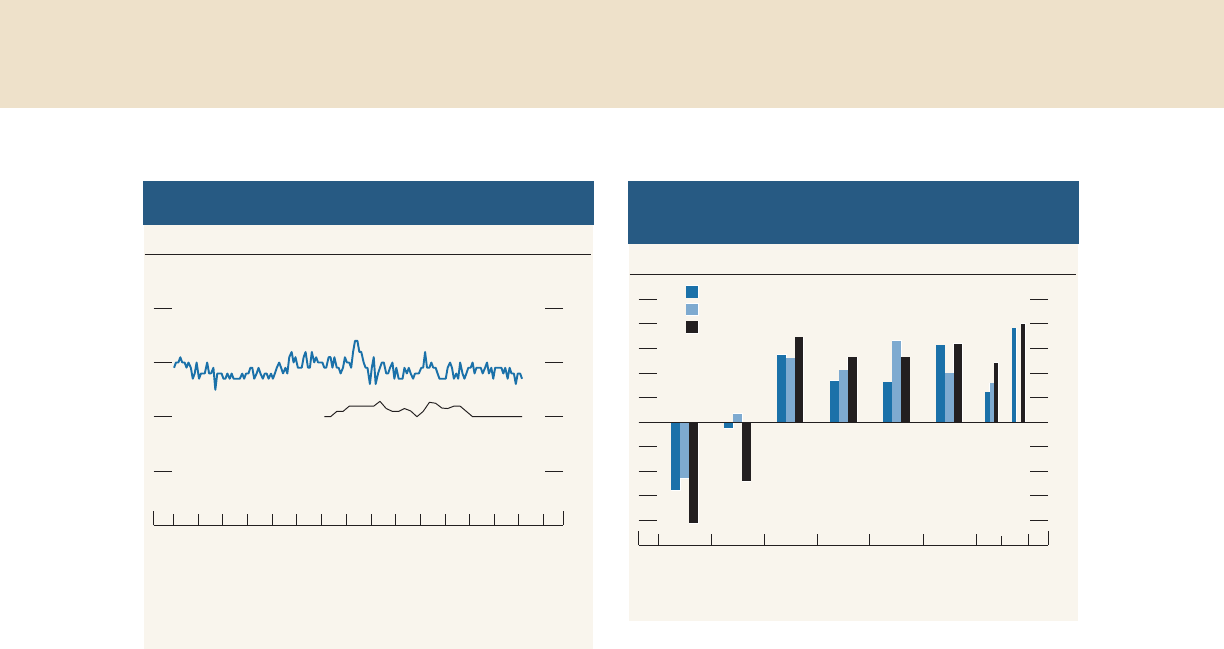

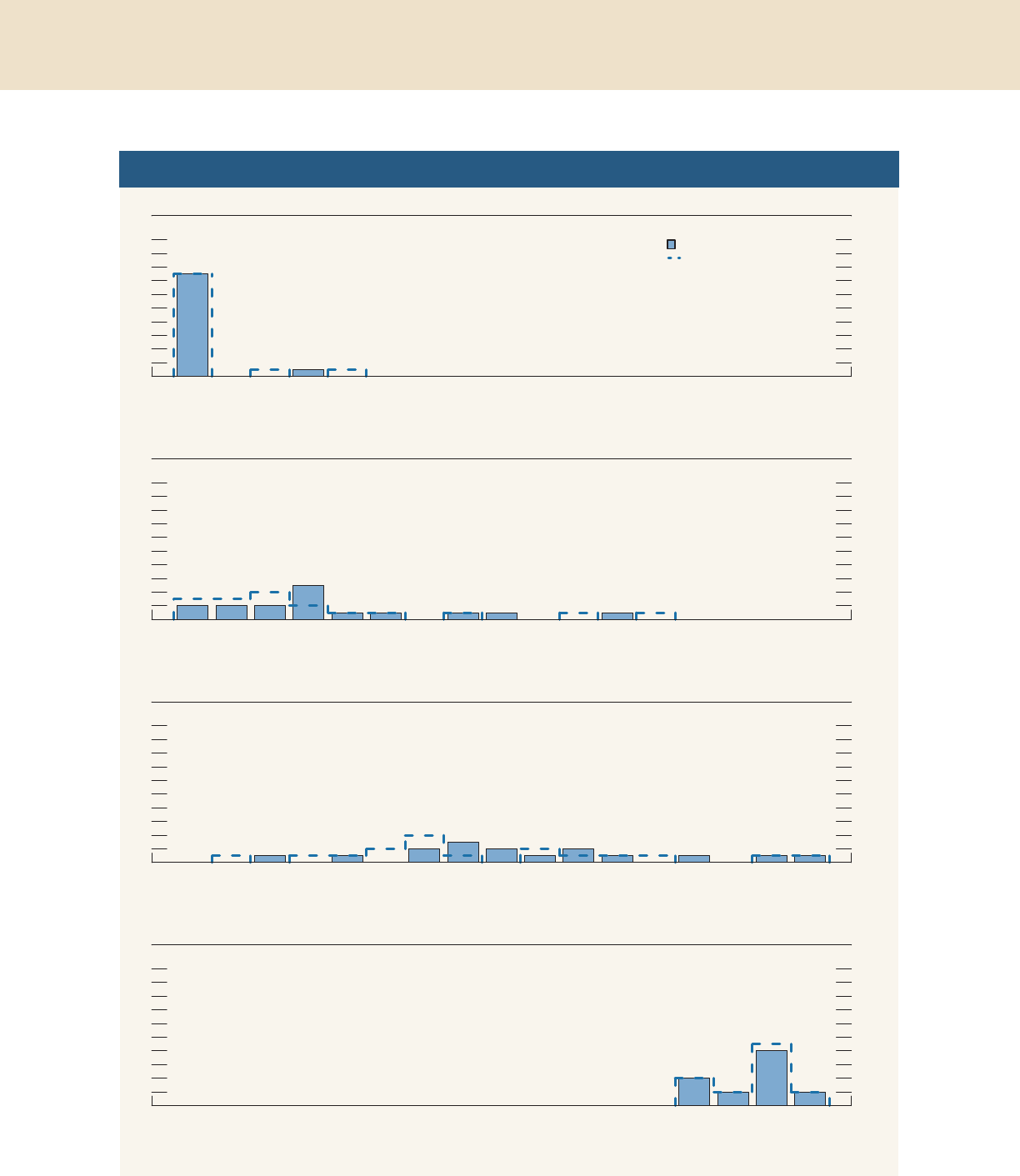

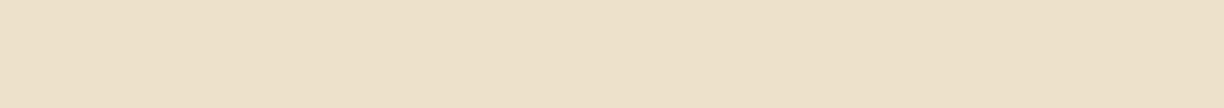

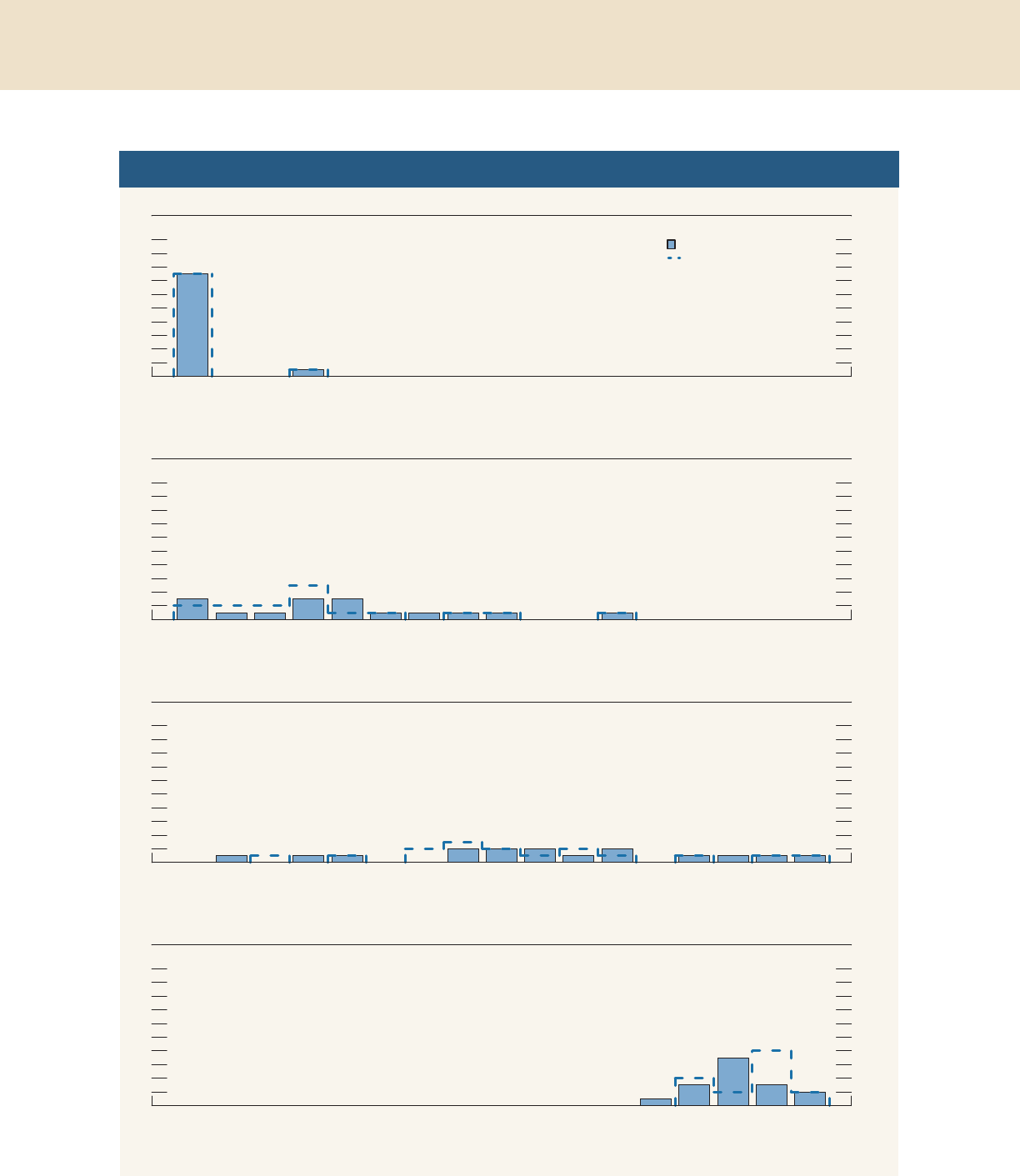

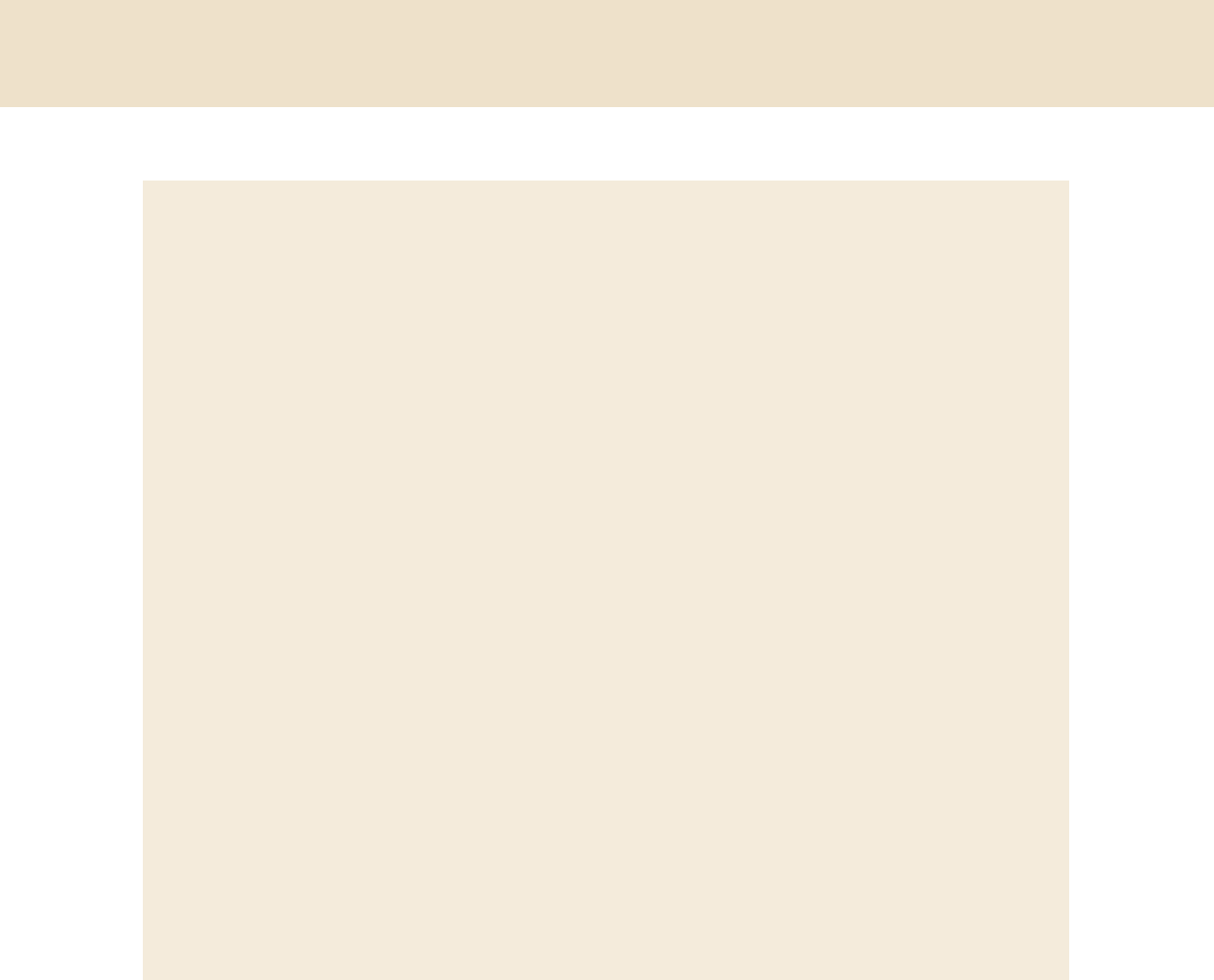

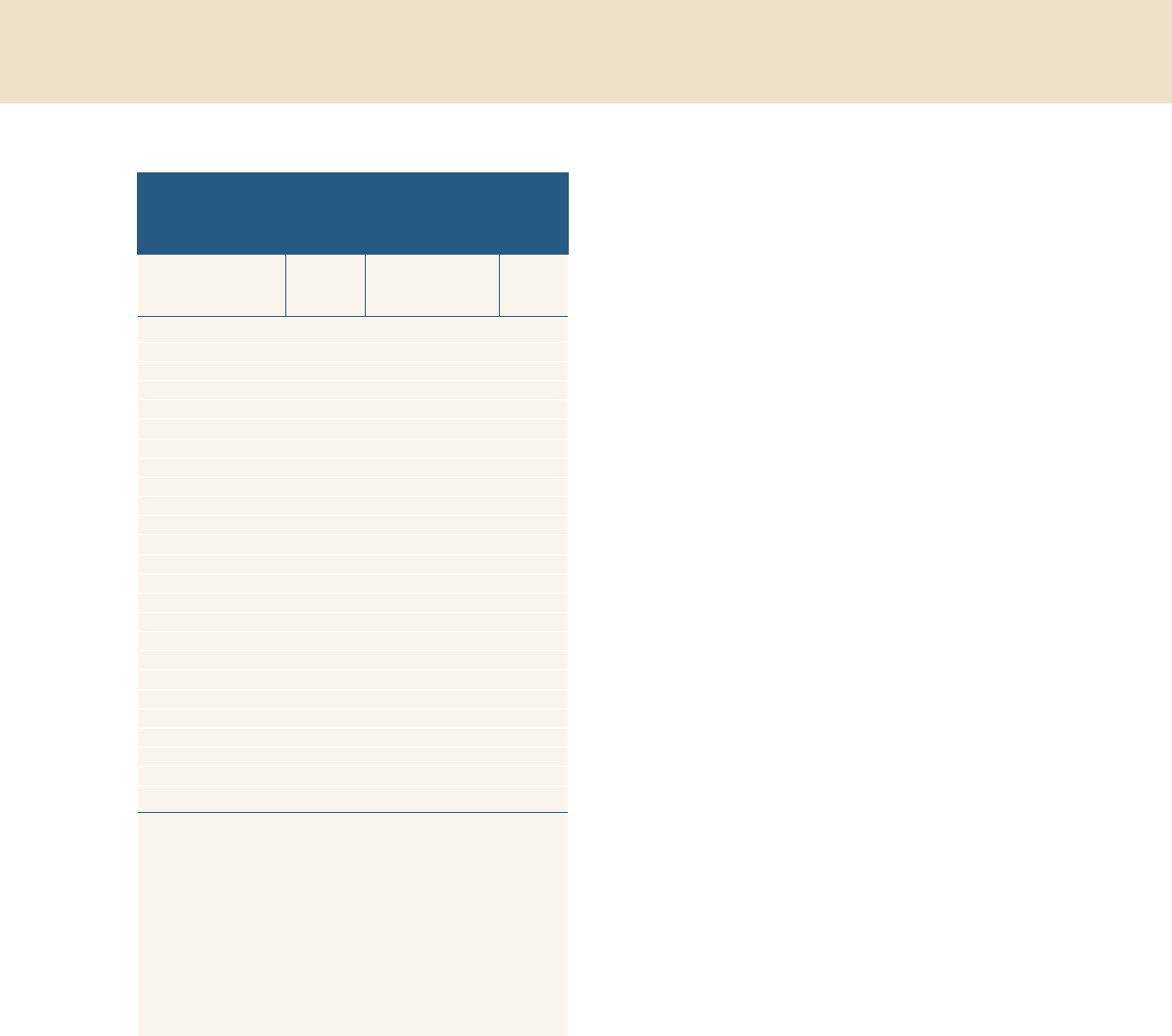

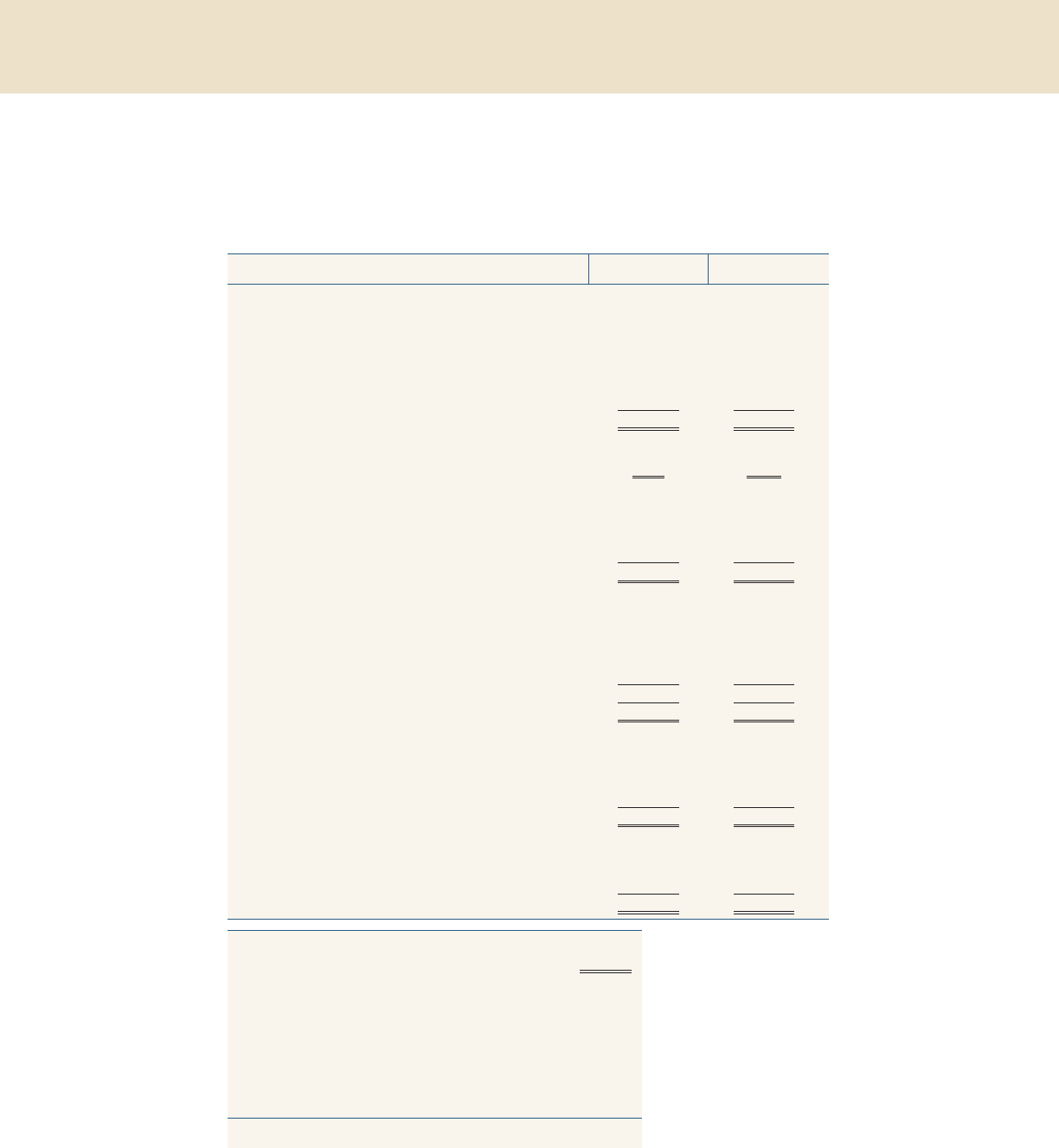

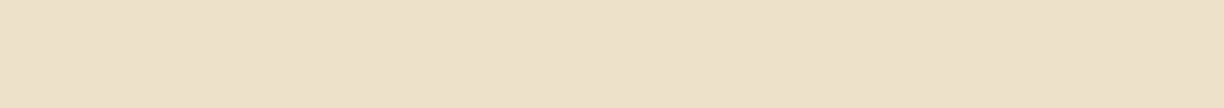

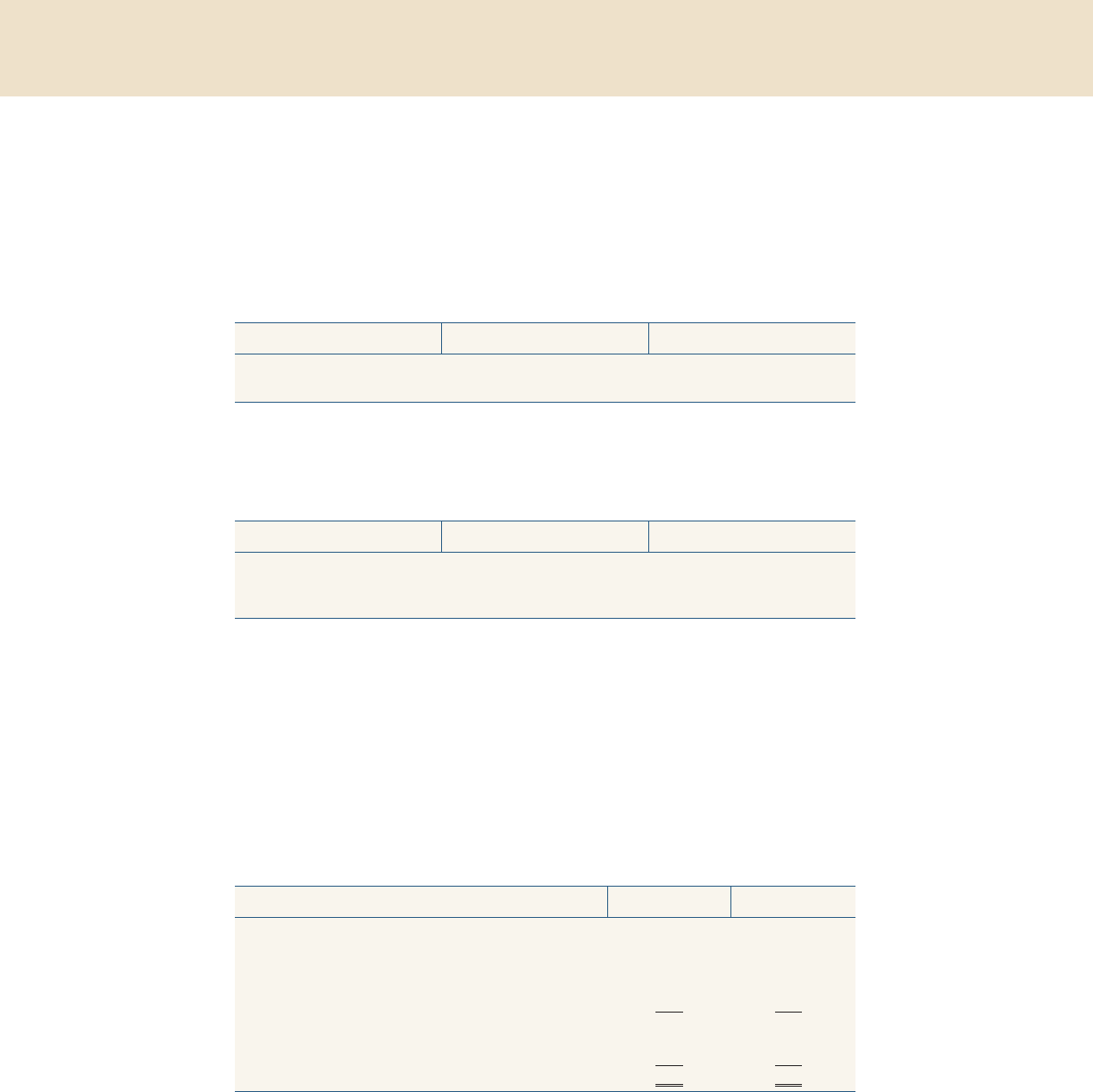

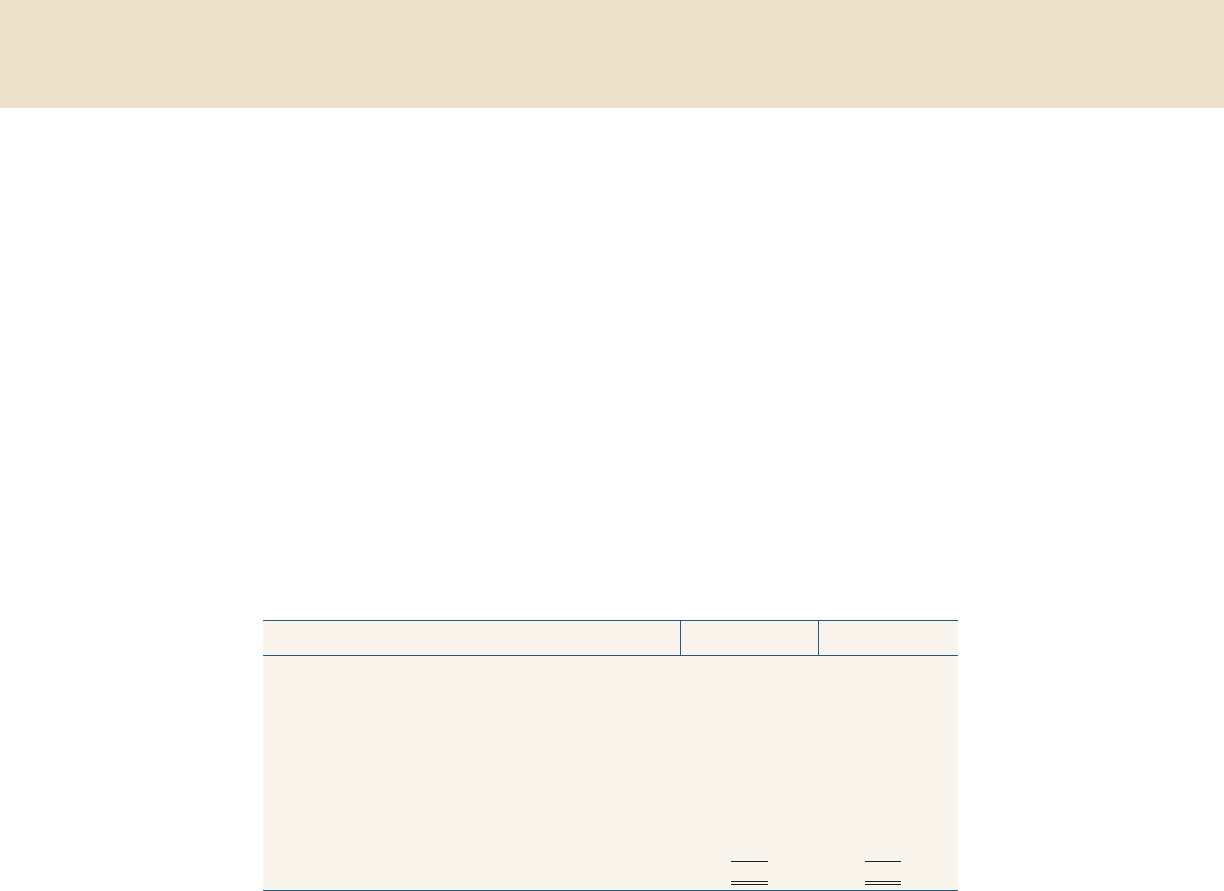

Figure 3. Brent spot and futures prices

Spot price

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

140

Dollars per barrel

20152014201320122011

Daily

Dec. 2017 futures contracts

Source: NYMEX.

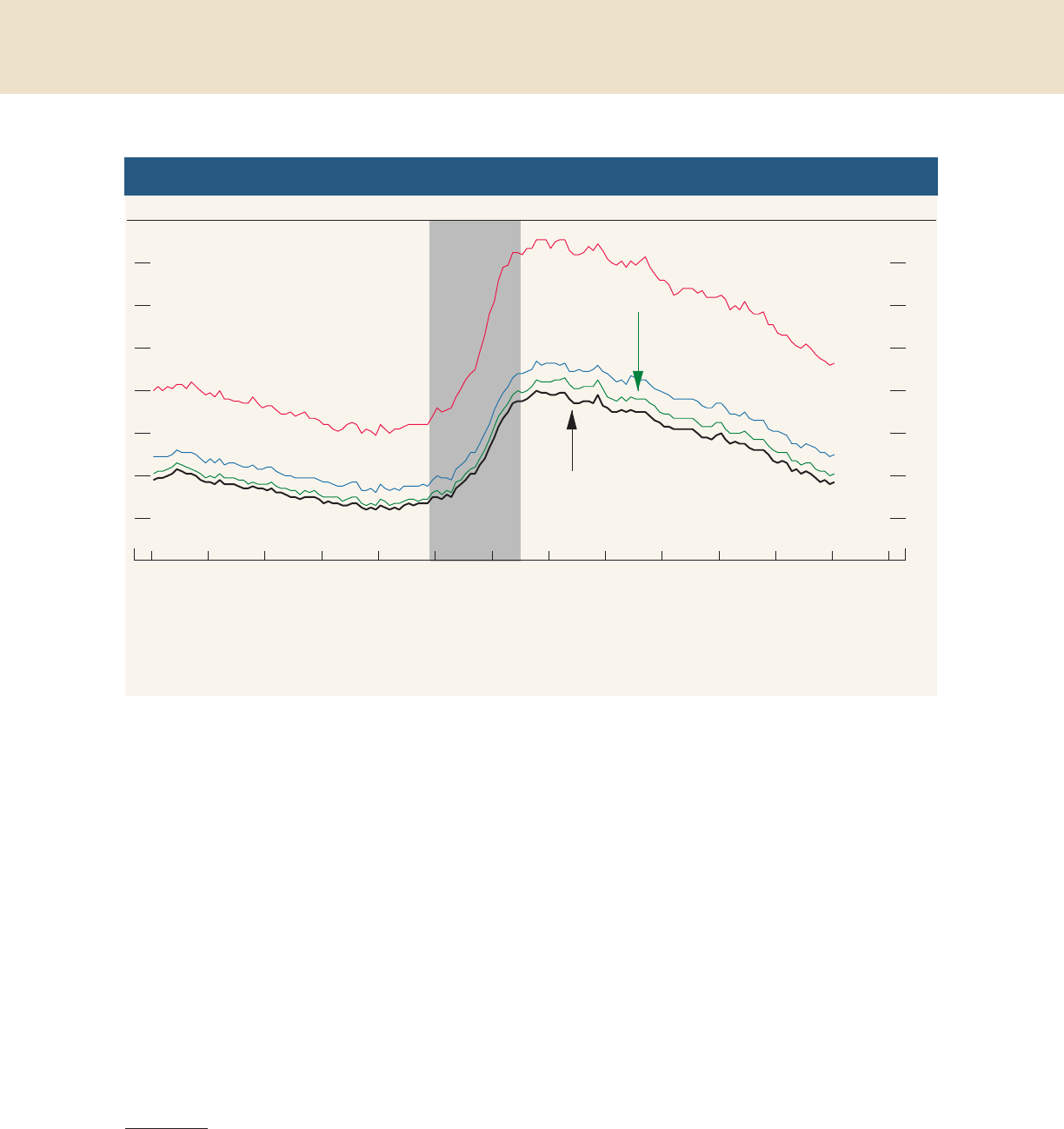

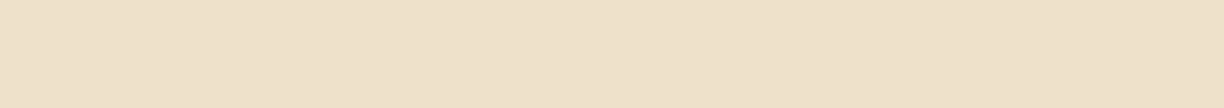

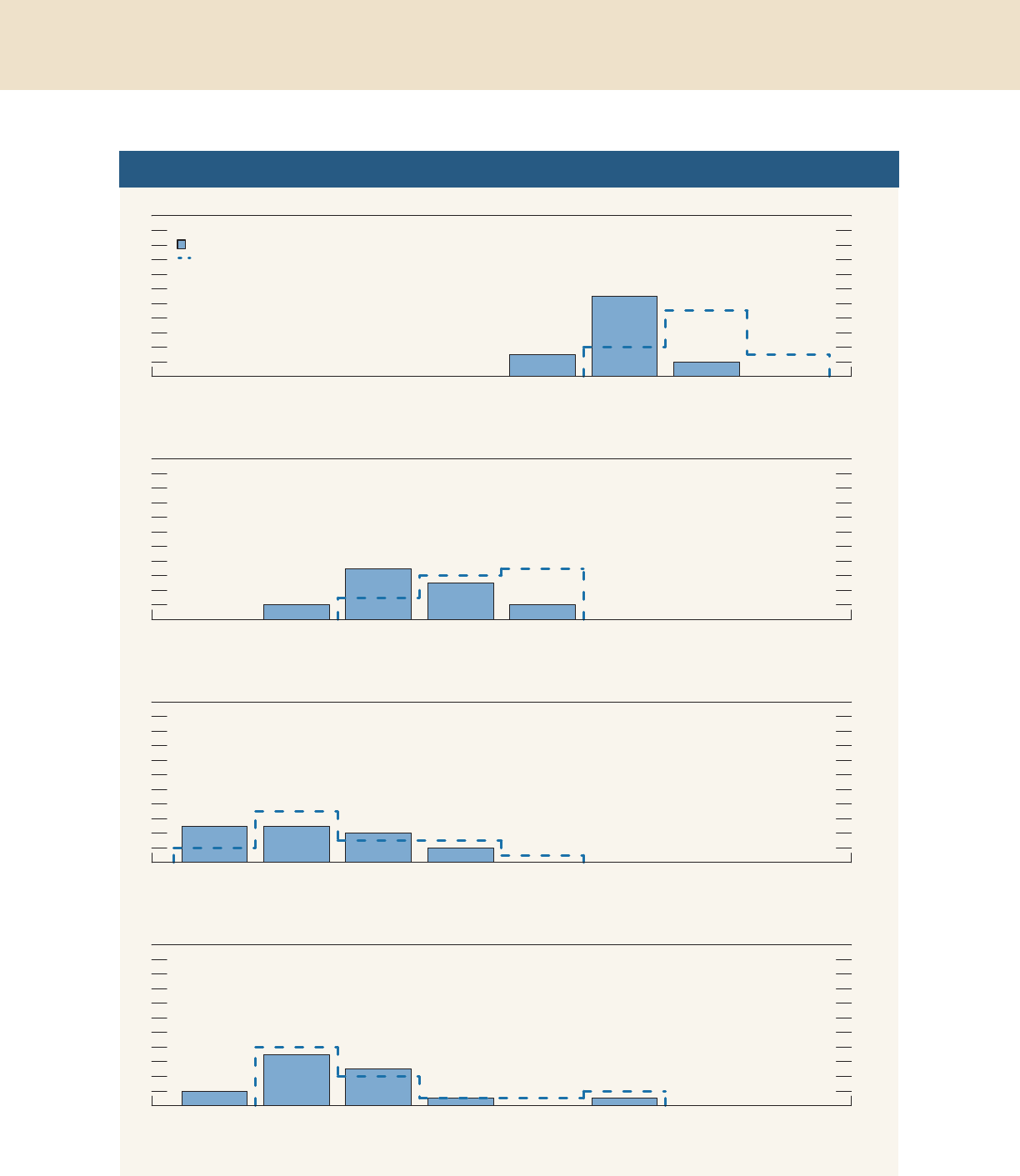

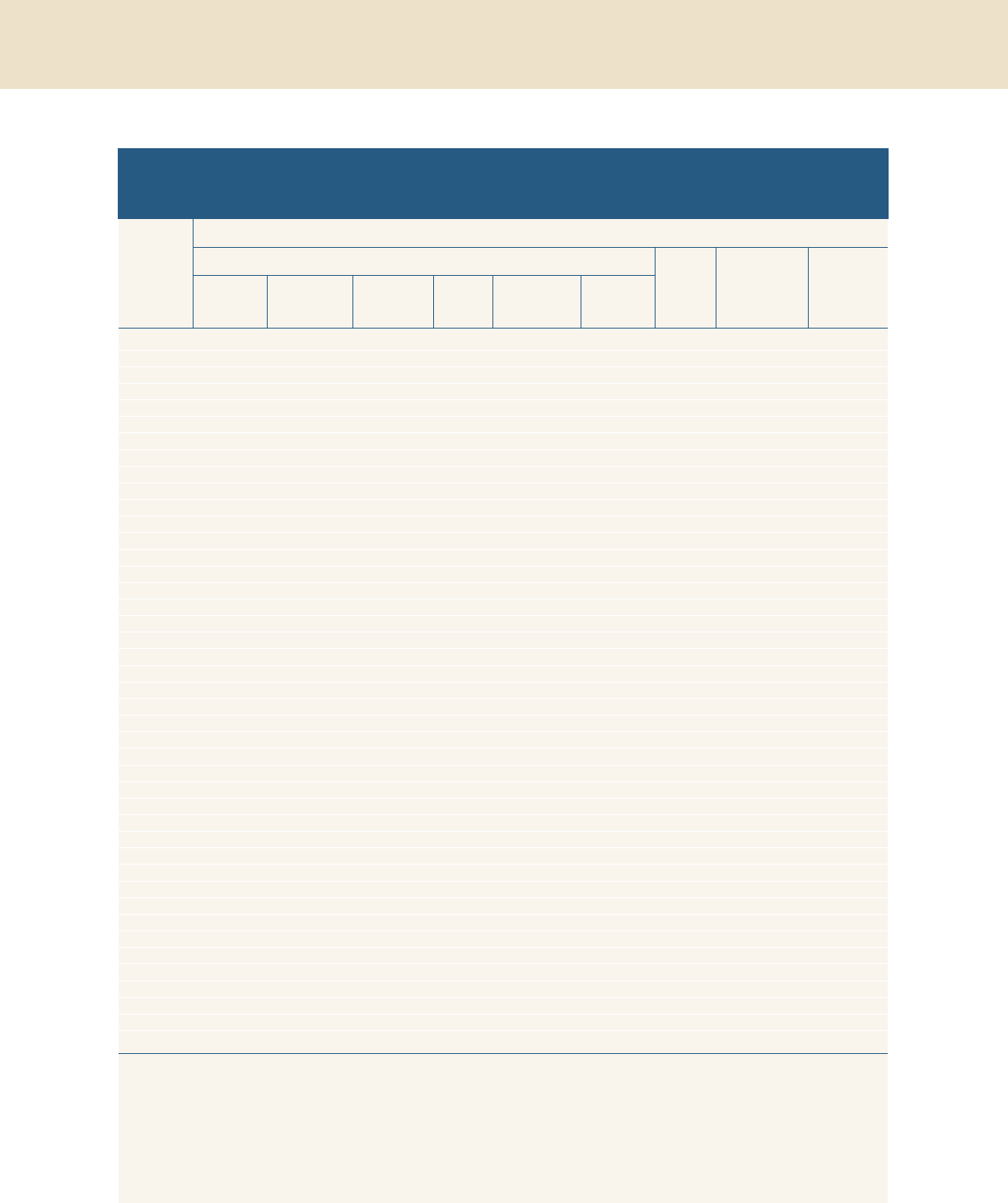

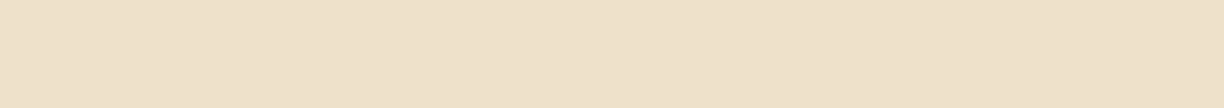

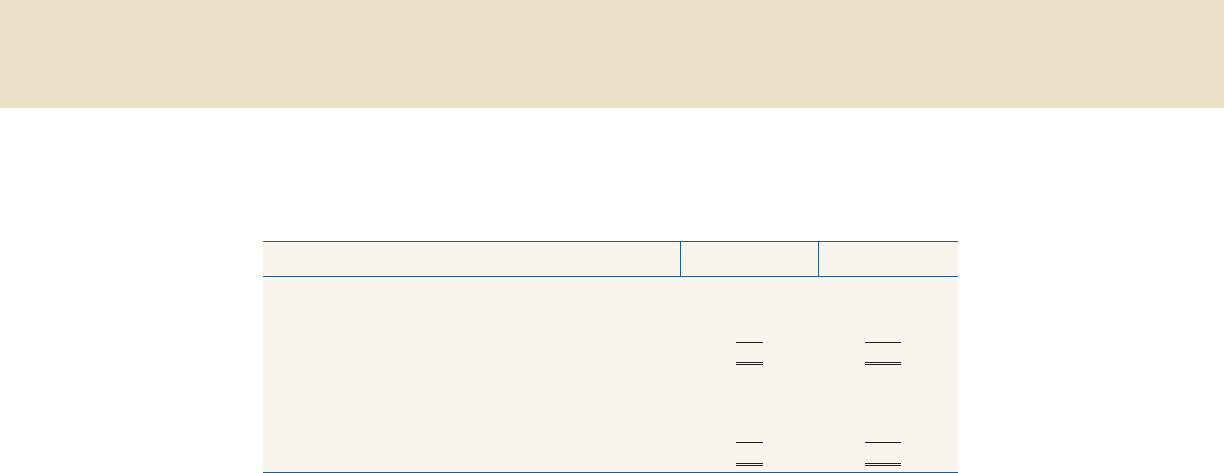

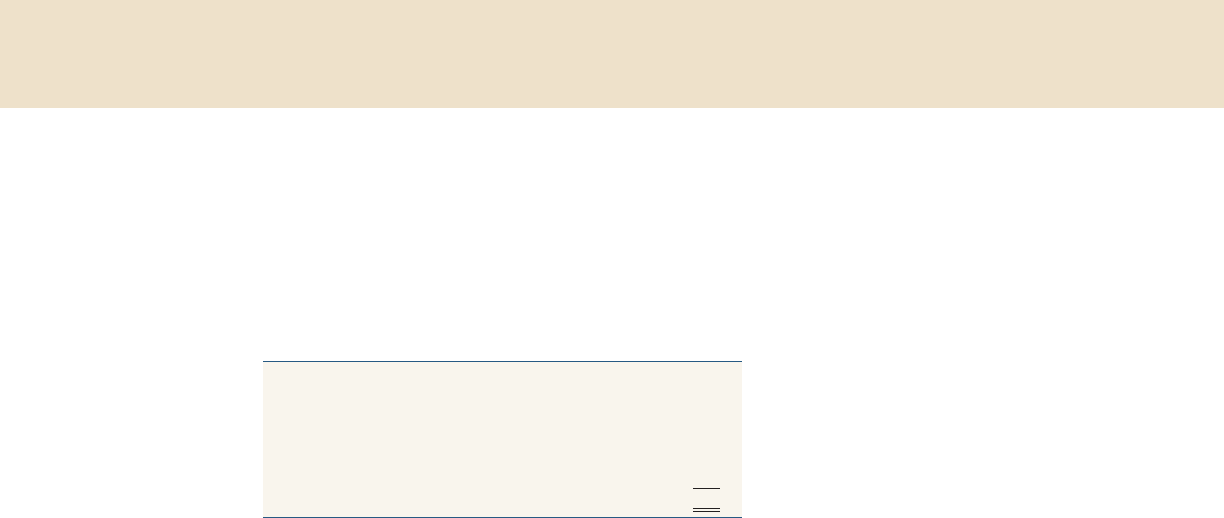

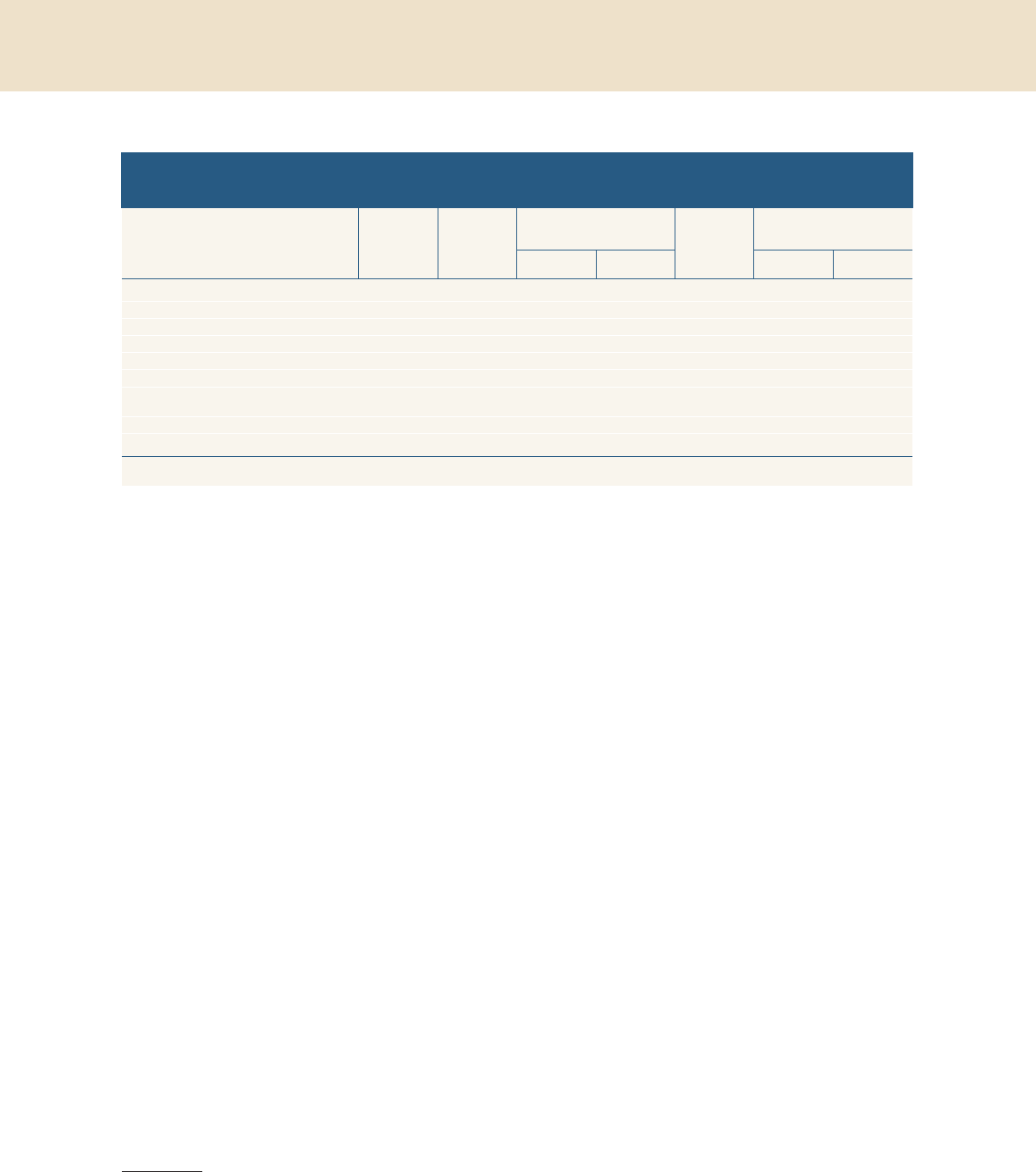

Figure 4. Change in the chain-type price index for personal

consumption expenditures

Excluding food

and energy

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

Percent

2014201320122011201020092008

Monthly

Total

Note: The data extend through December 2014; changes are from one year

earlier.

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments 9

been quite stable over the past 15 years; in particular,

they have changed little, on net, over the past few

years (

figure 5). In contrast, measures of longer-term

inflation compensation derived from financial market

instruments have fallen noticeably during the past

several months. As is discussed in more detail in the

box “

Challenges in Interpreting Measures of Longer-

Term Inflation Expectations

” on pages 12–13 of the

February 2015 Monetary Policy Report, deducing the

sources of changes in inflation compensation is diffi-

cult because such movements may be caused by fac-

tors other than shifts in market participants’ inflation

expectations.

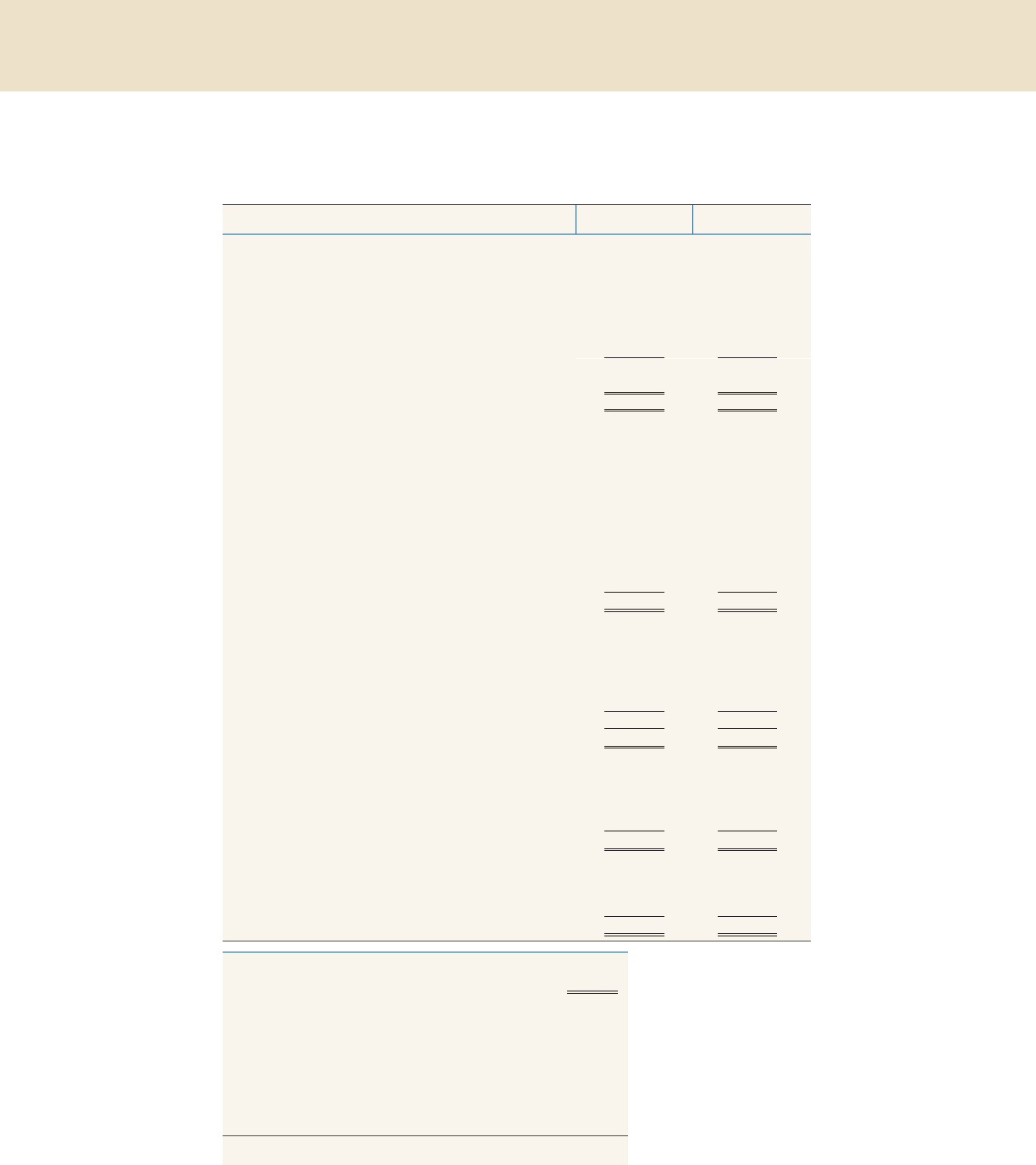

Economic activity expanded at a strong pace in

the second half of 2014

Real GDP is estimated to have increased at an annual

rate of 3¾ percent in the second half of last year

after a reported increase of just 1¼ percent in the

first half, when output was likely restrained by severe

weather and other transitory factors (

figure 6). Pri-

vate domestic final purchases—a measure of house-

hold and business spending that tends to exhibit less

quarterly variation than GDP—also advanced at a

substantial pace in the second half of last year.

The second-half gains in GDP reflected solid

advances in consumer spending and in business

investment spending on equipment and intangibles

(E&I) as well as subdued gains for both residential

investment and nonresidential structures. More gen-

erally, the growth in GDP has been supported by

accommodative financial conditions, including

declines in the cost of borrowing for many house-

holds and businesses; by a reduction in the restraint

from fiscal policy relative to 2013; and by increases in

spending spurred by continuing job gains and, more

recently, by falling oil prices. The gains in GDP have

occurred despite an appreciating U.S. dollar and con-

cerns about global economic growth, which remain

an important source of uncertainty for the economic

outlook.

Consumer spending was supported by

continuing improvement in the labor market and

falling oil prices, . . .

Real PCE rose at an annual rate of 3¾ percent in the

second half of 2014—a noticeable step-up from the

sluggish rate of only about 2 percent in the first half

(

figure 7). The increases in spending have been sup-

ported by the improving labor market. In addition,

the fall in gasoline and other energy prices has

boosted purchasing power for consumers, especially

those in lower- and middle-income brackets who

spend a sizable share of their income on gasoline.

Real disposable personal income—that is, income

after taxes and adjusted for price changes—rose

3 percent at an annual rate in the second half of last

year, roughly double the average rate recorded over

the preceding five years.

. . . further increases in household wealth and

low interest rates, . . .

Consumer spending growth was also likely supported

by further increases in household net worth, as the

stock market continued to rise and house prices

moved up in the second half of last year. The value

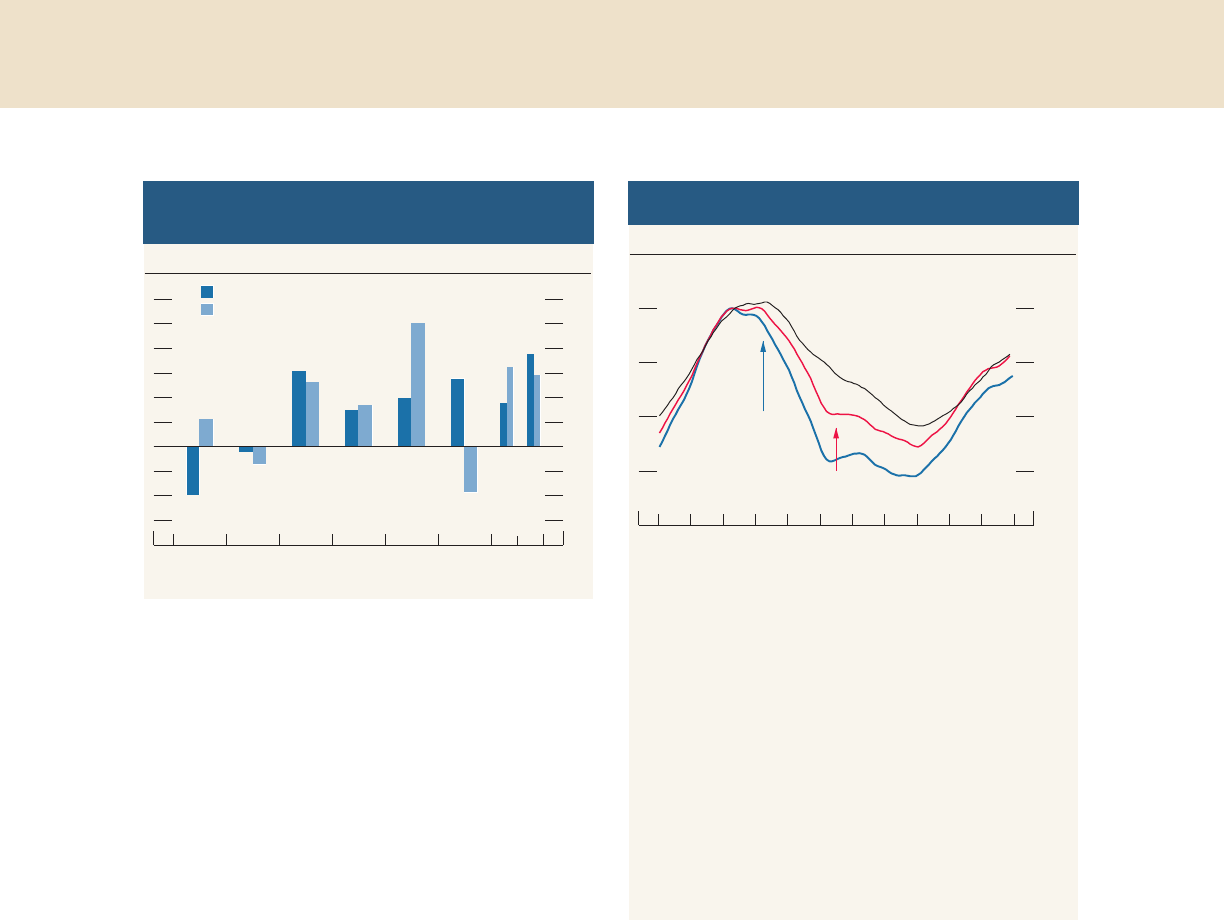

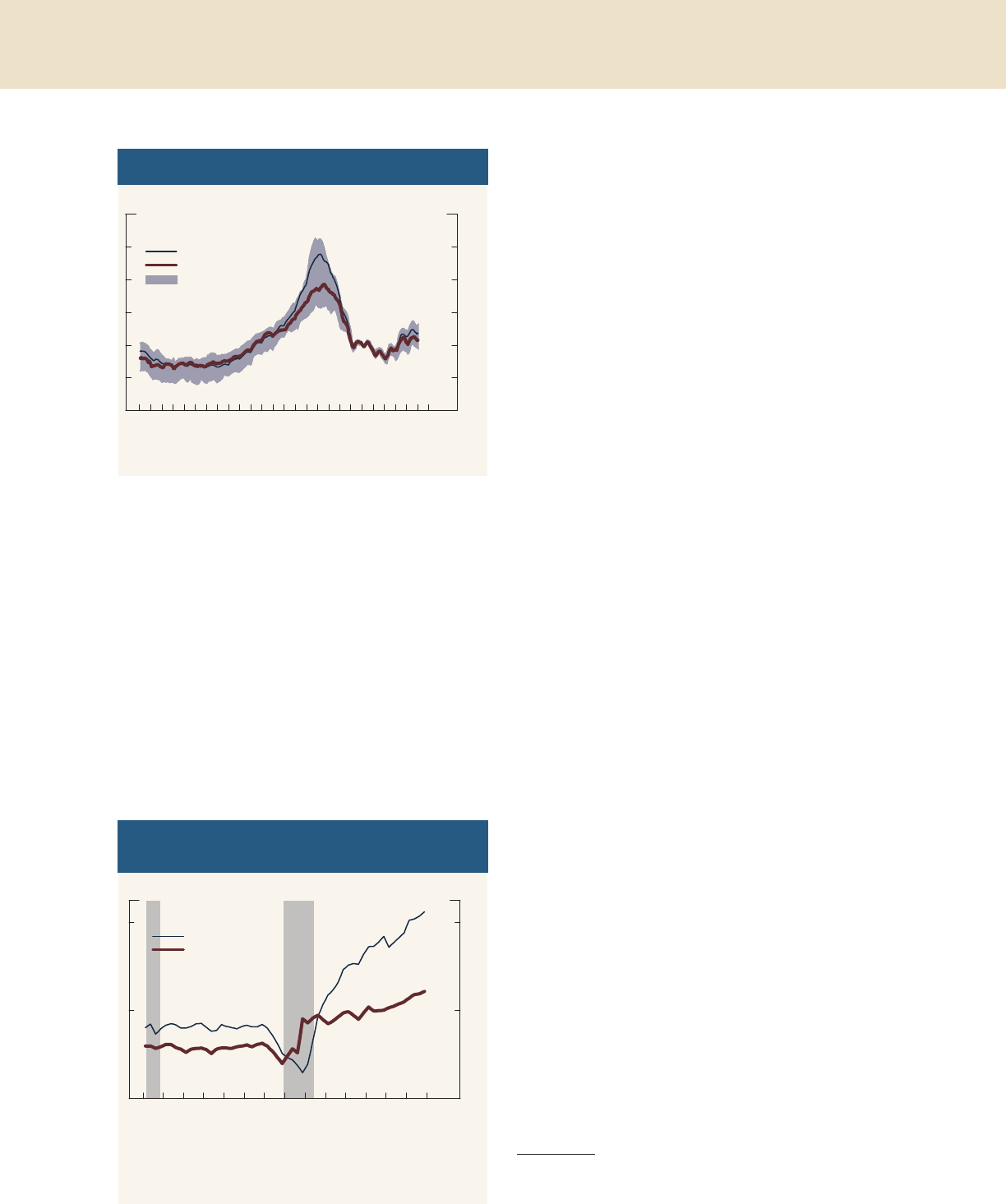

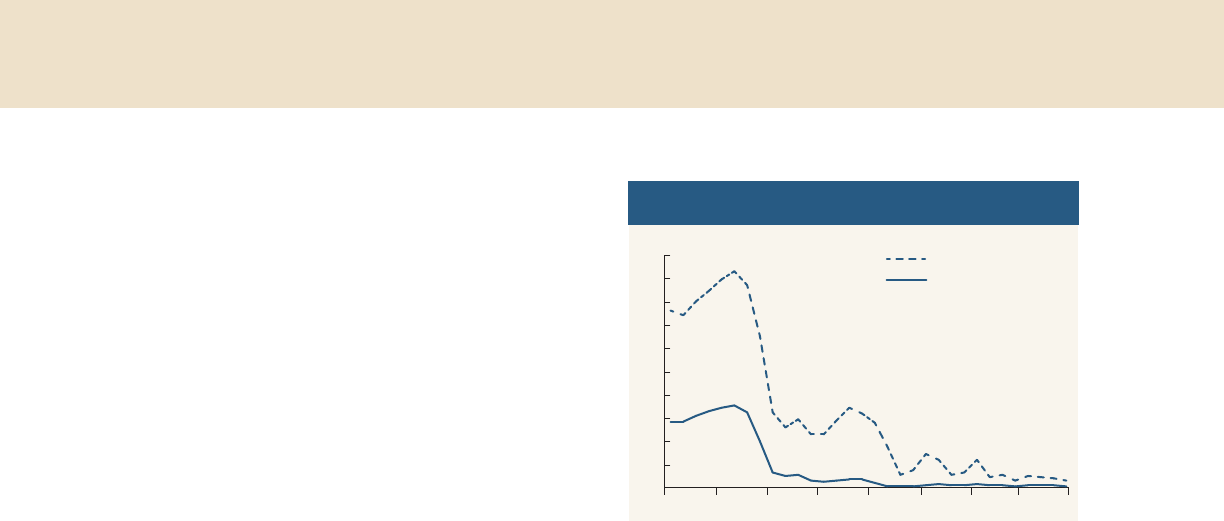

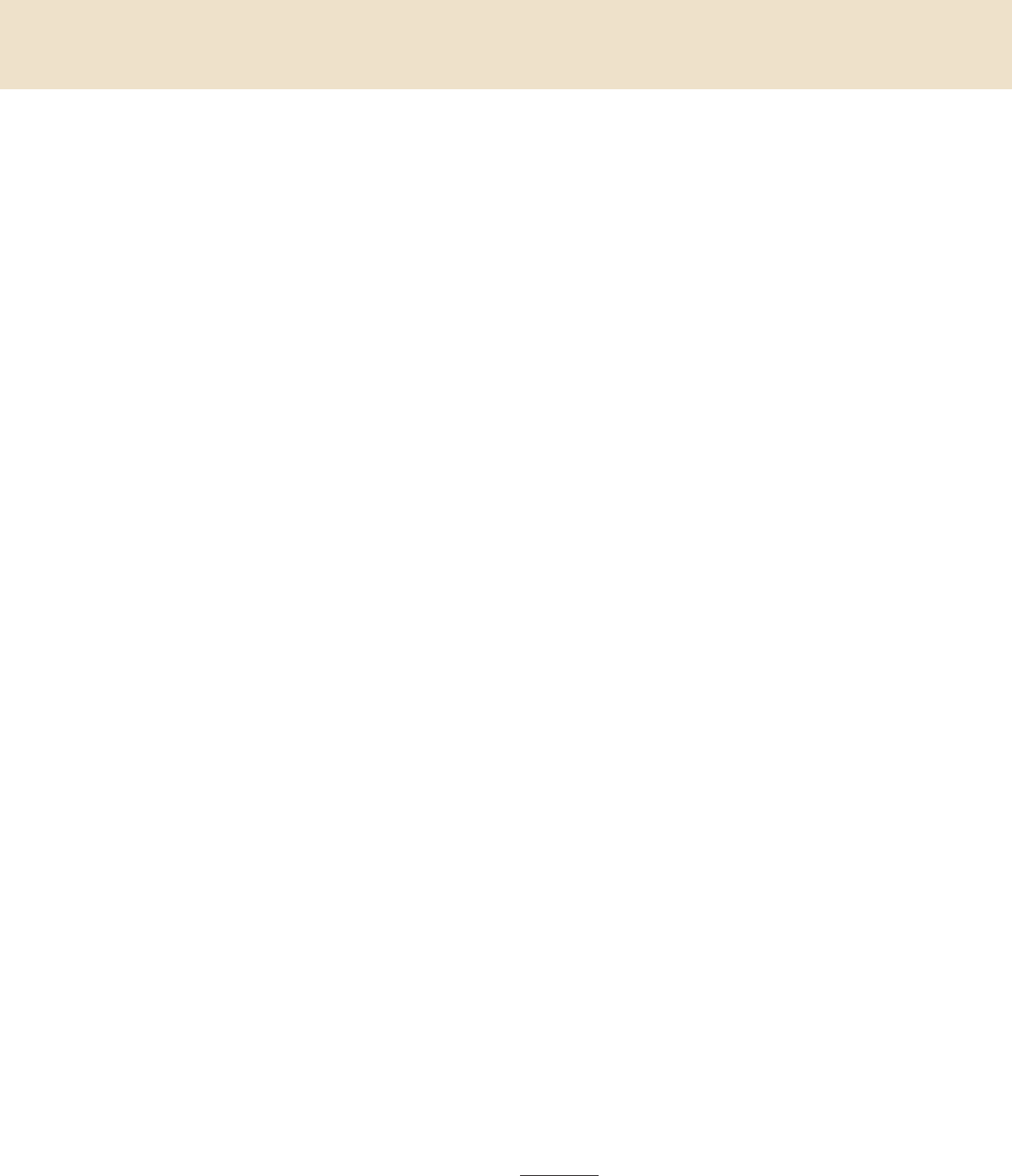

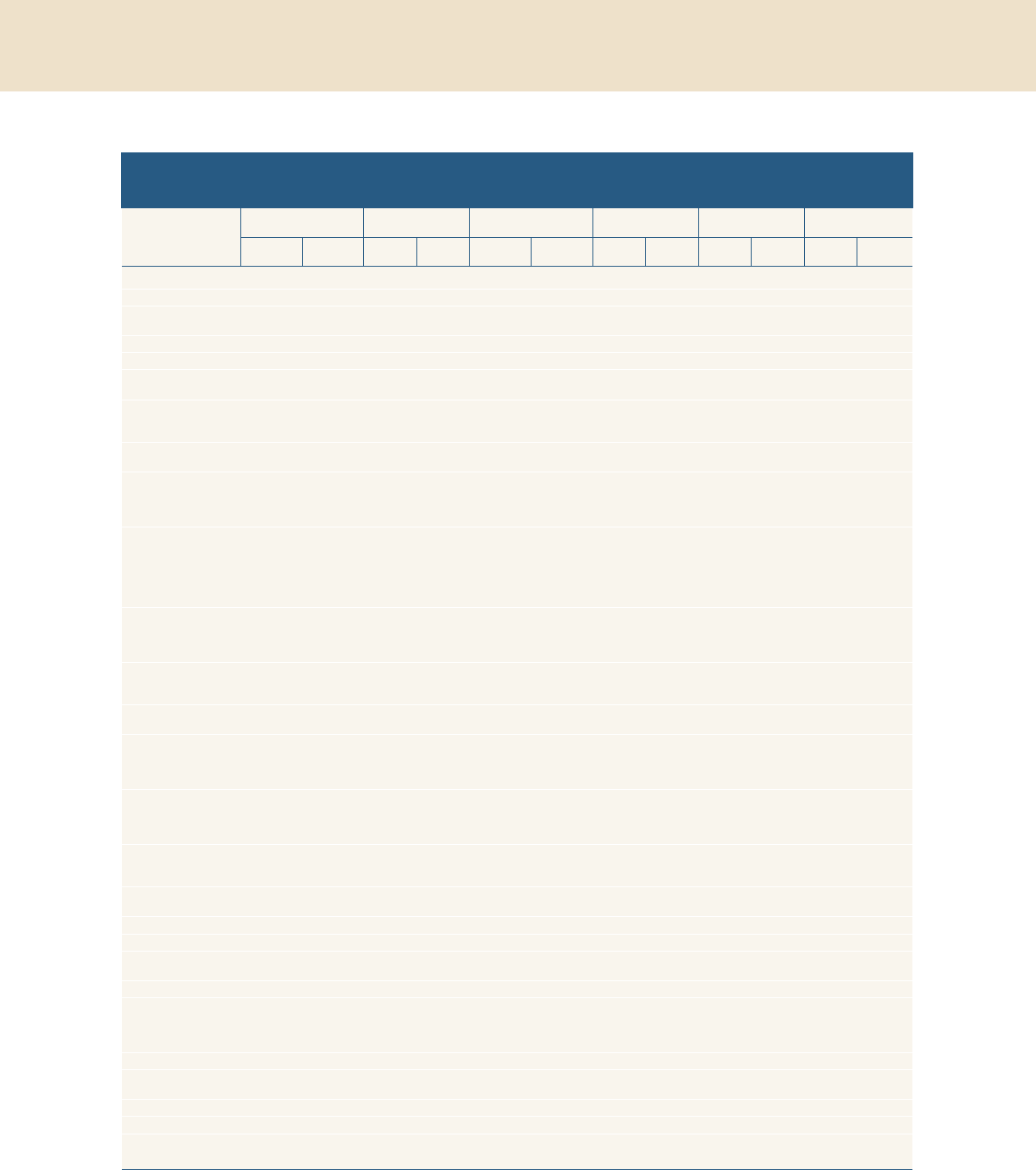

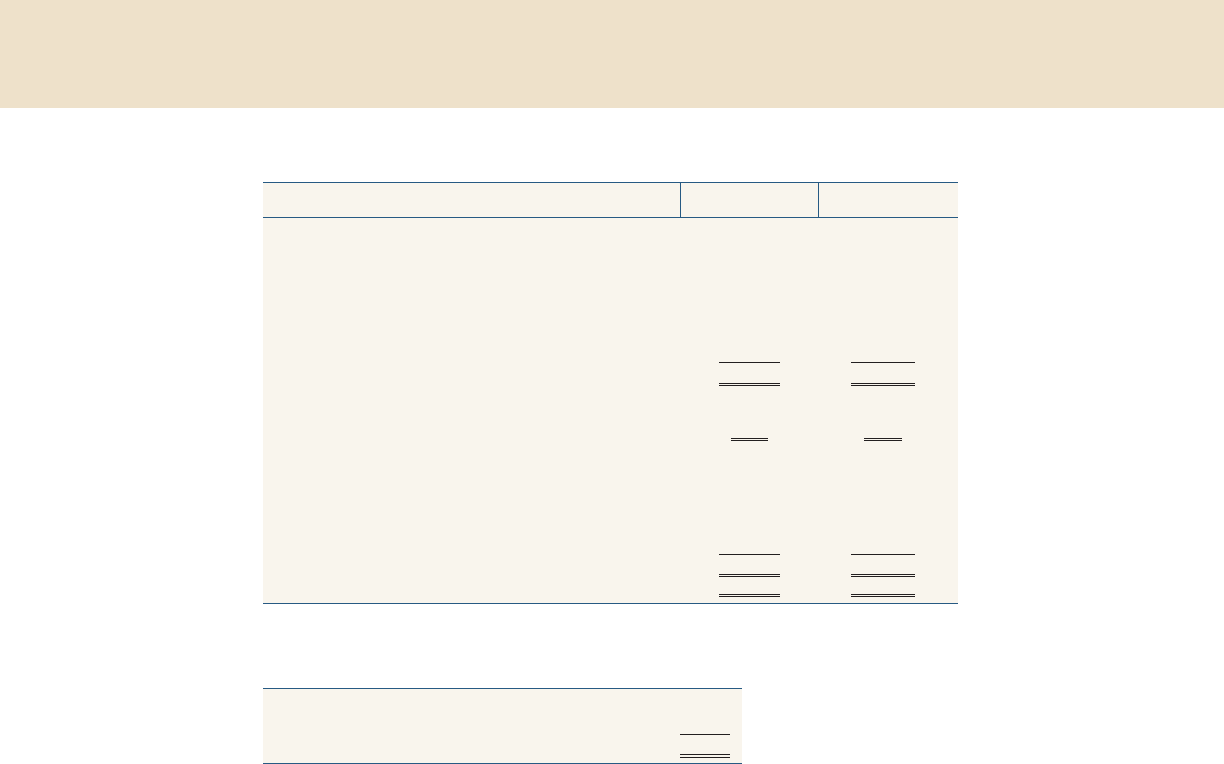

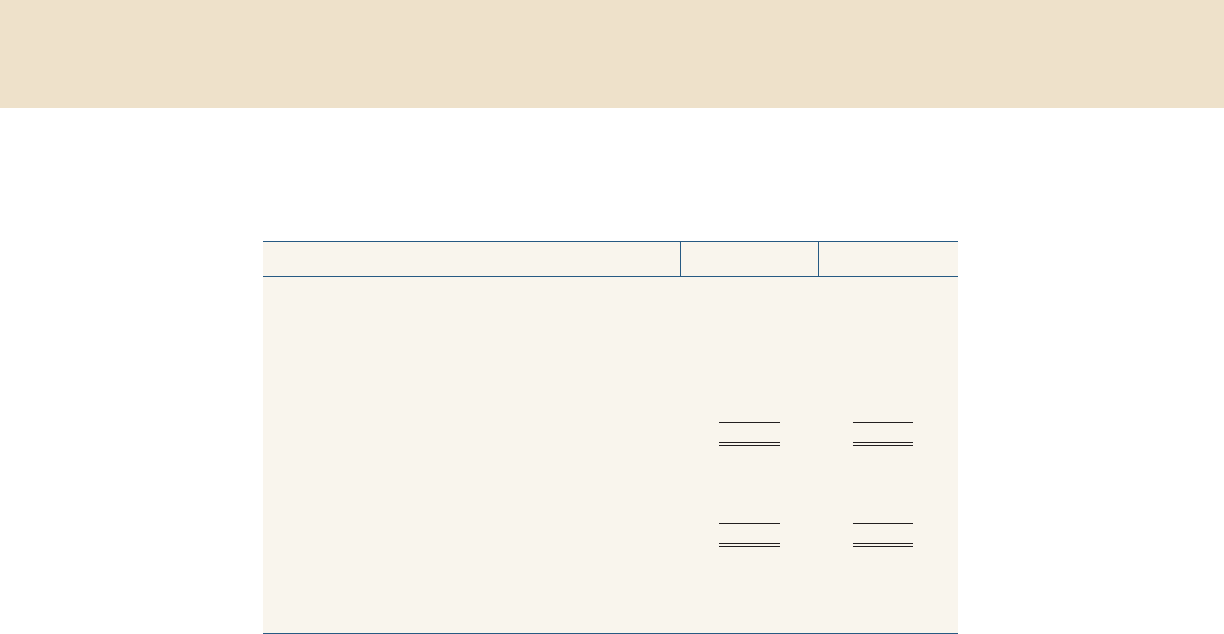

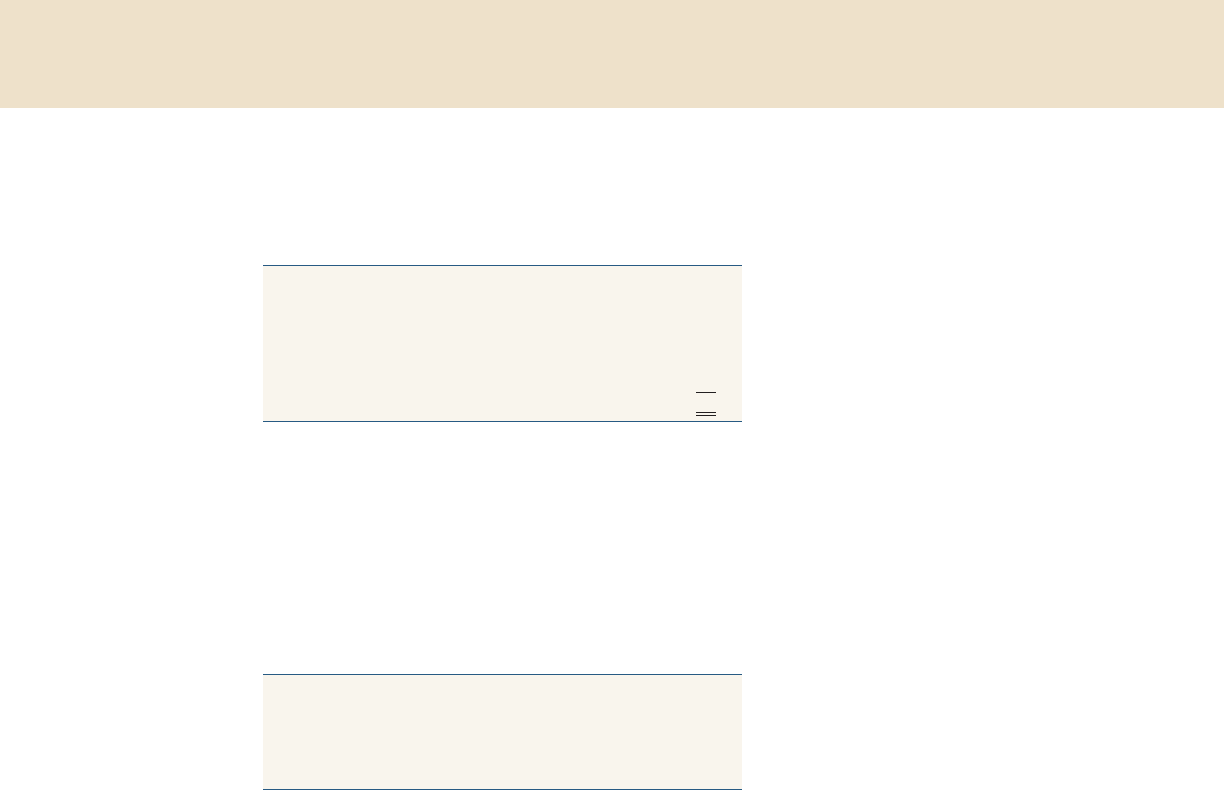

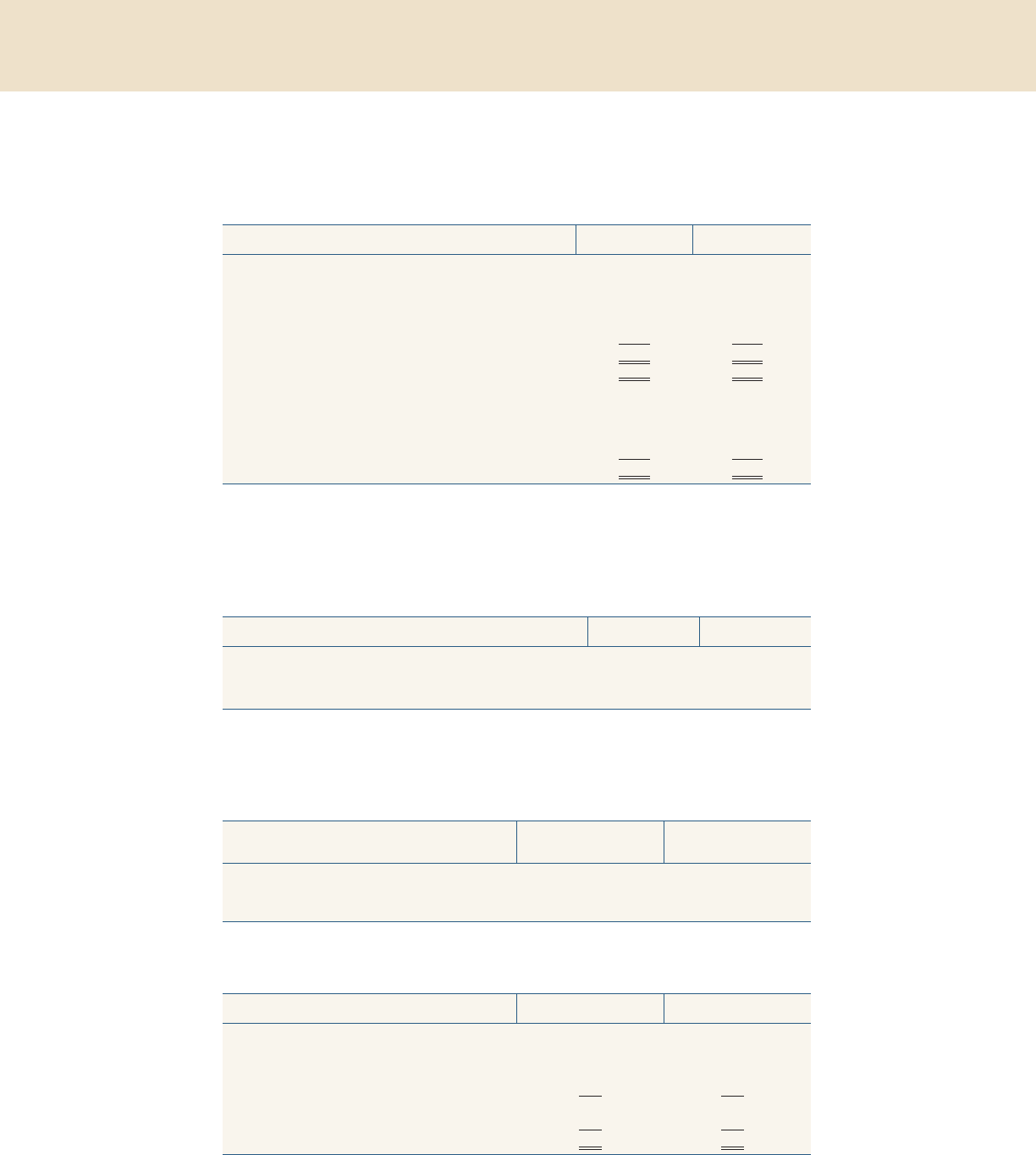

Figure 5. Median inflation expectations

Michigan survey expectations

for next 5 to 10 years

1

2

3

4

Percent

20152013201120092007200520032001

SPF expectations

for next 10 years

Note: The Michigan survey data are monthly and extend through February 2015.

The SPF data for inflation expectations for personal consumption expenditures are

quarterly and extend from 2007:Q1 through 2015:Q1.

Source: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Survey of Professional

Forecasters (SPF).

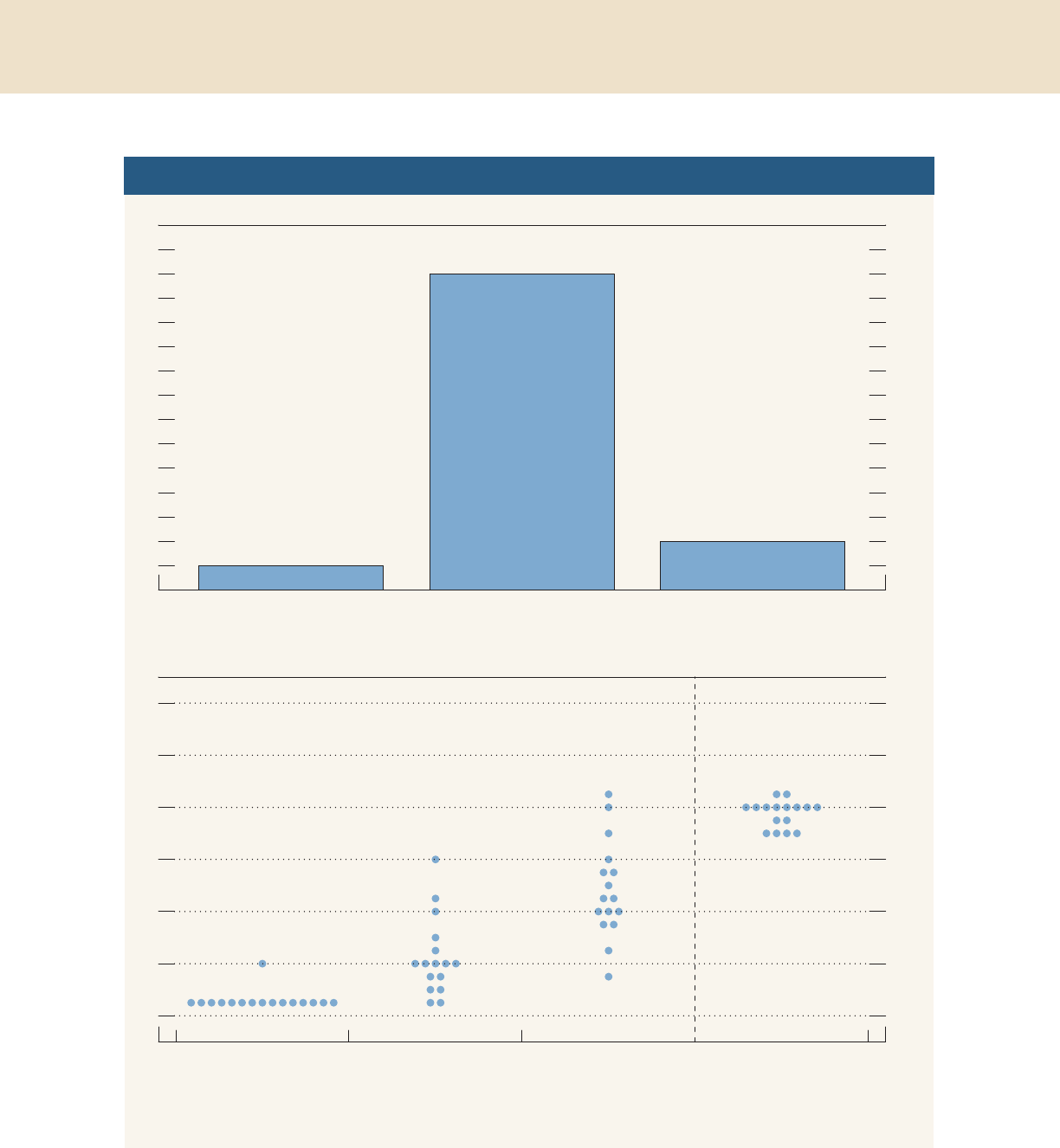

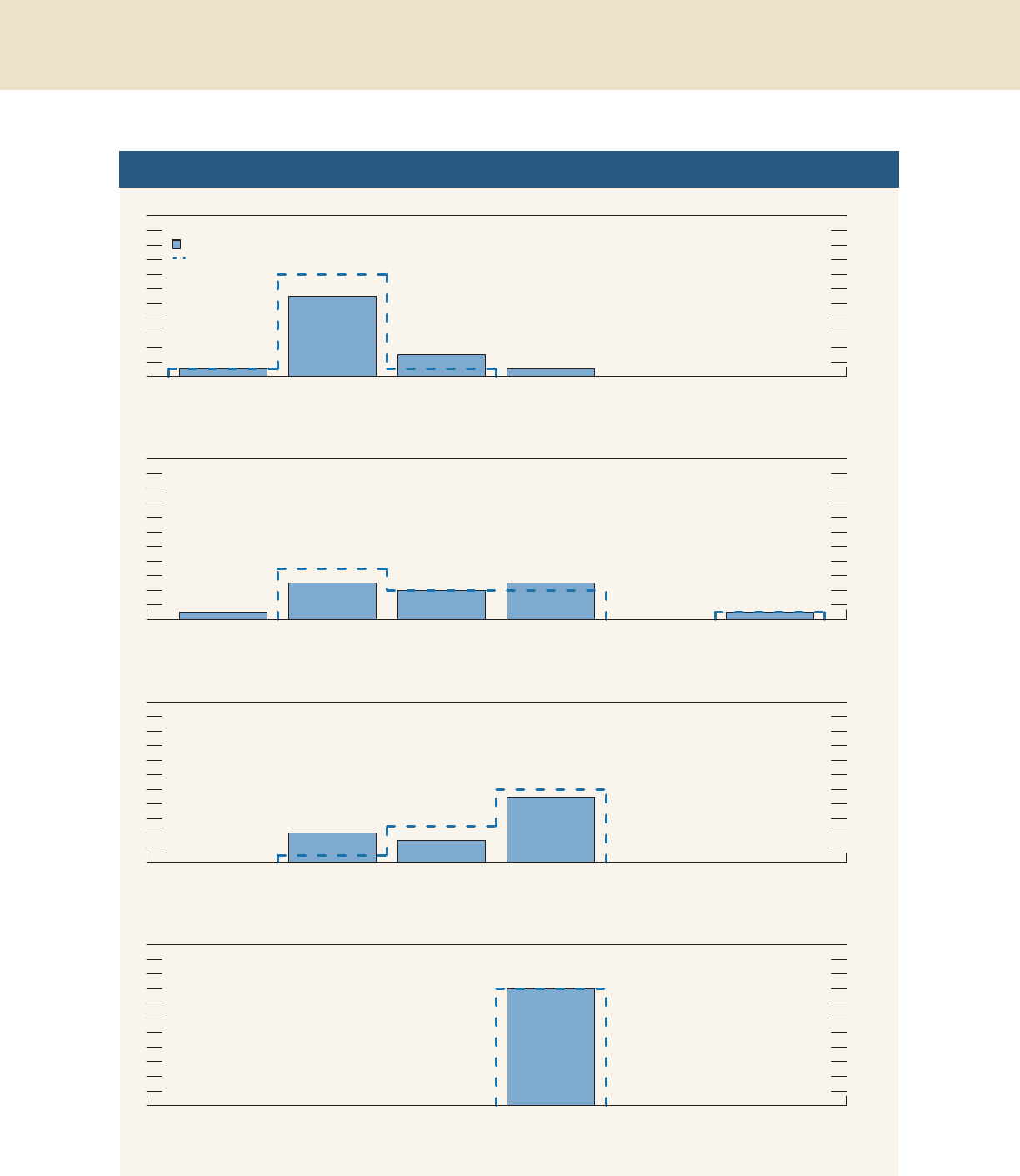

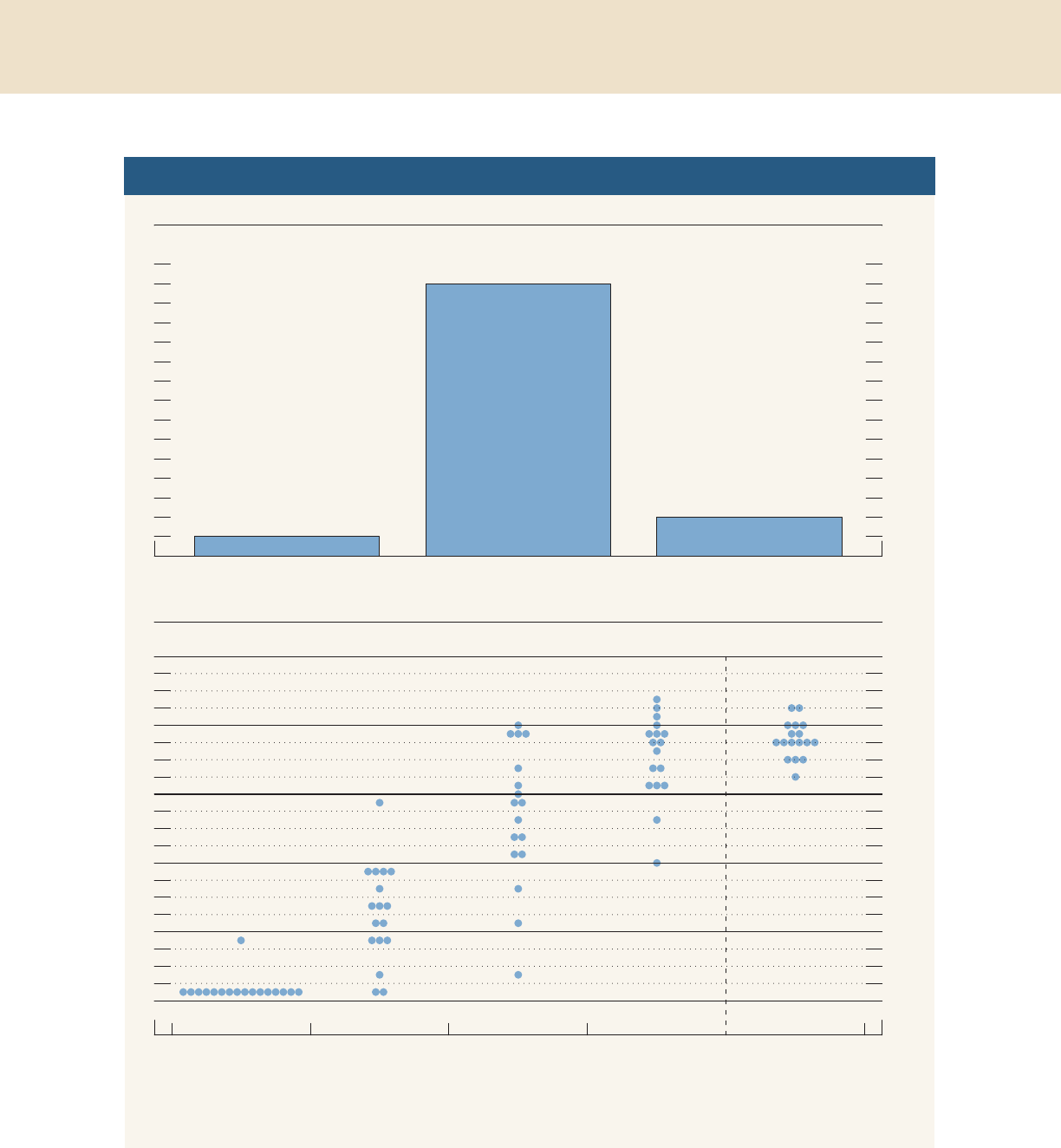

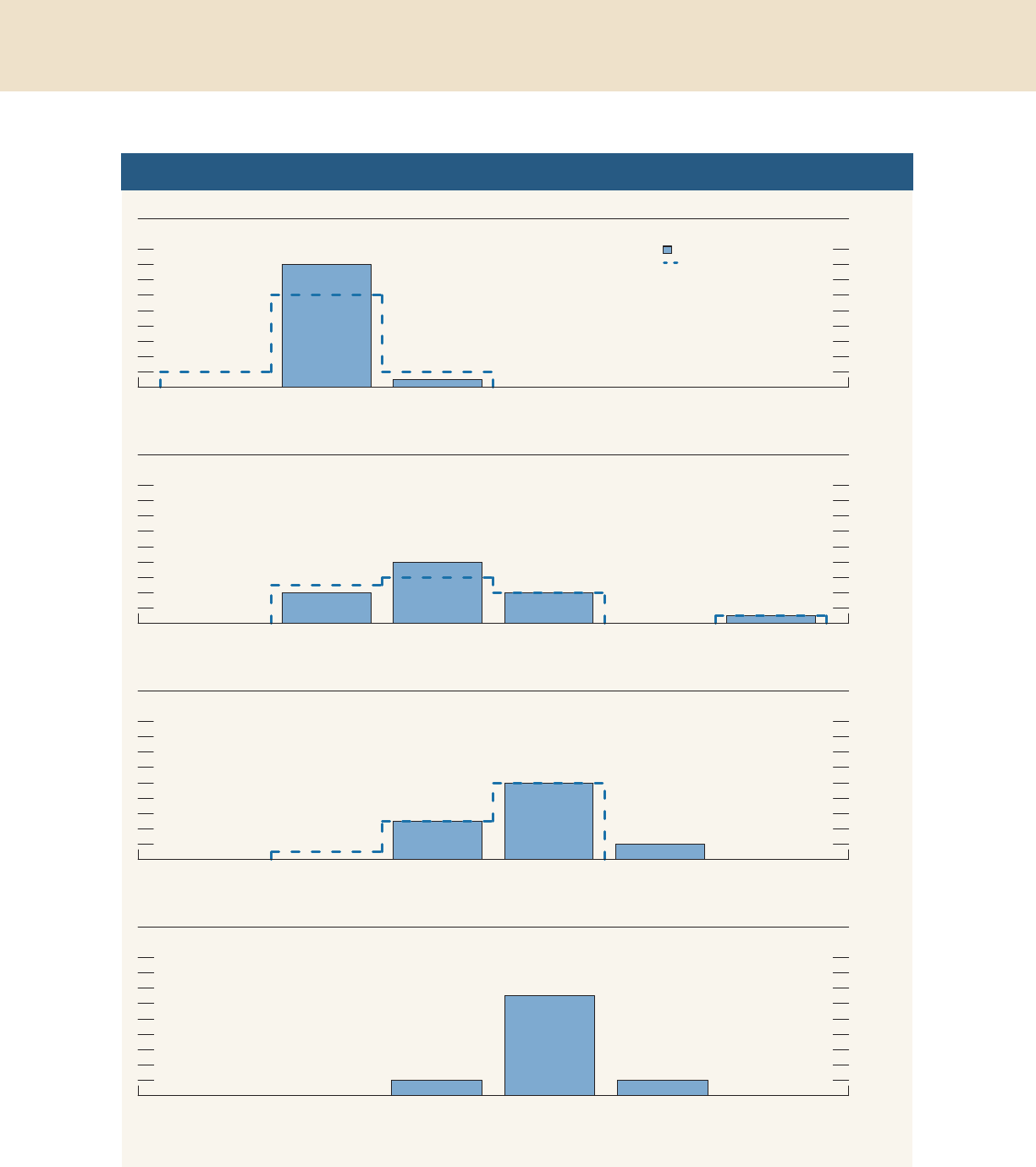

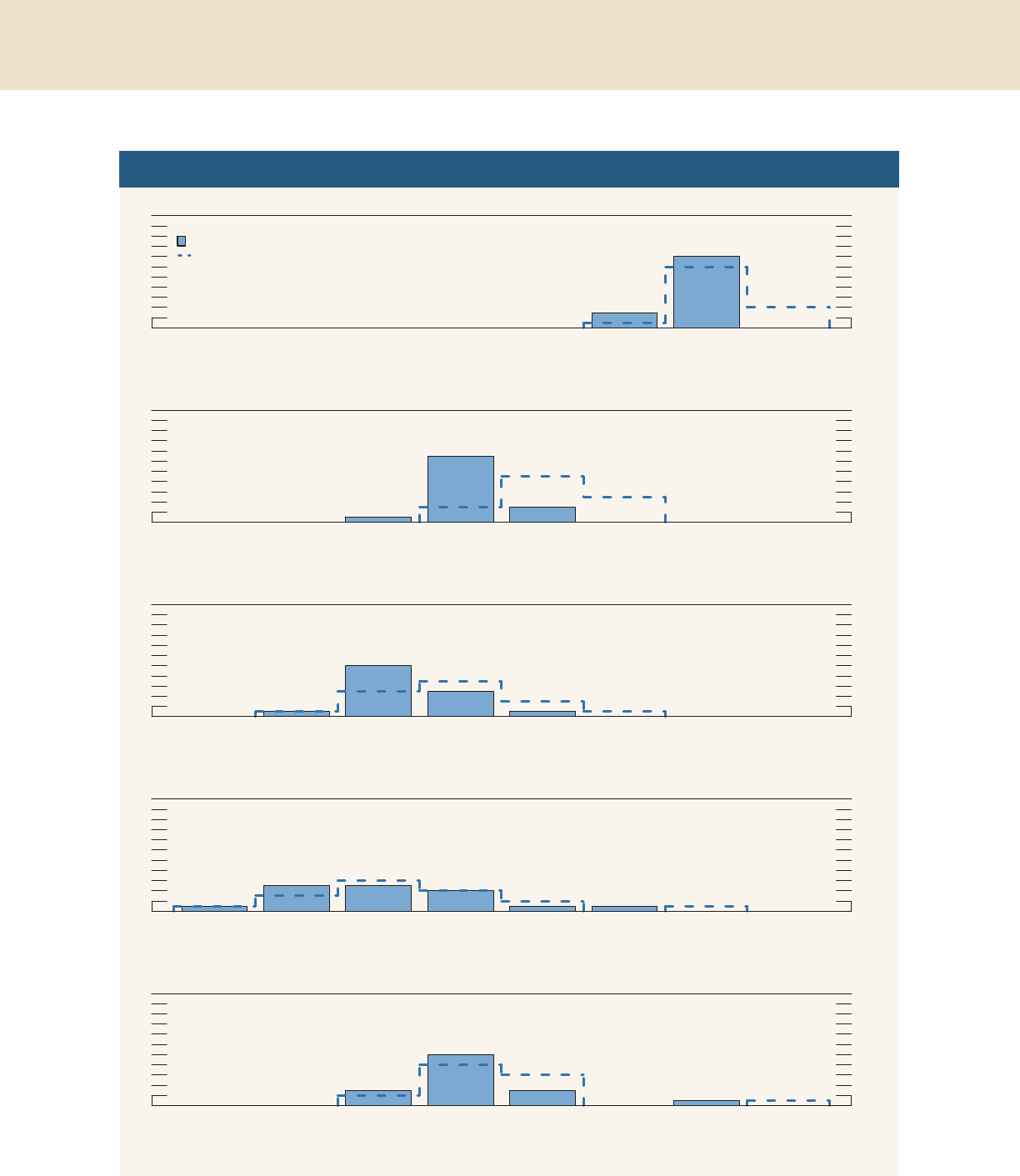

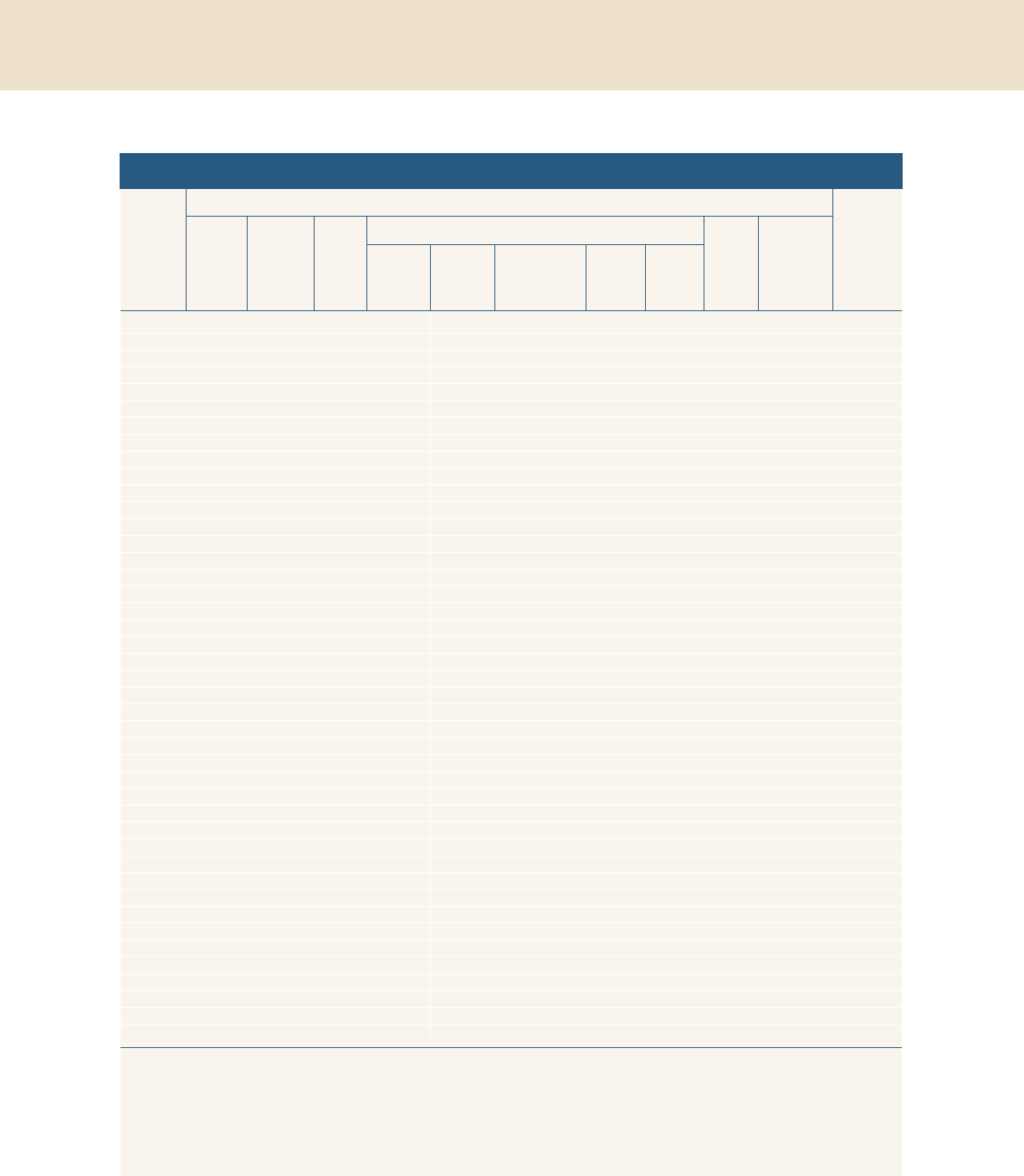

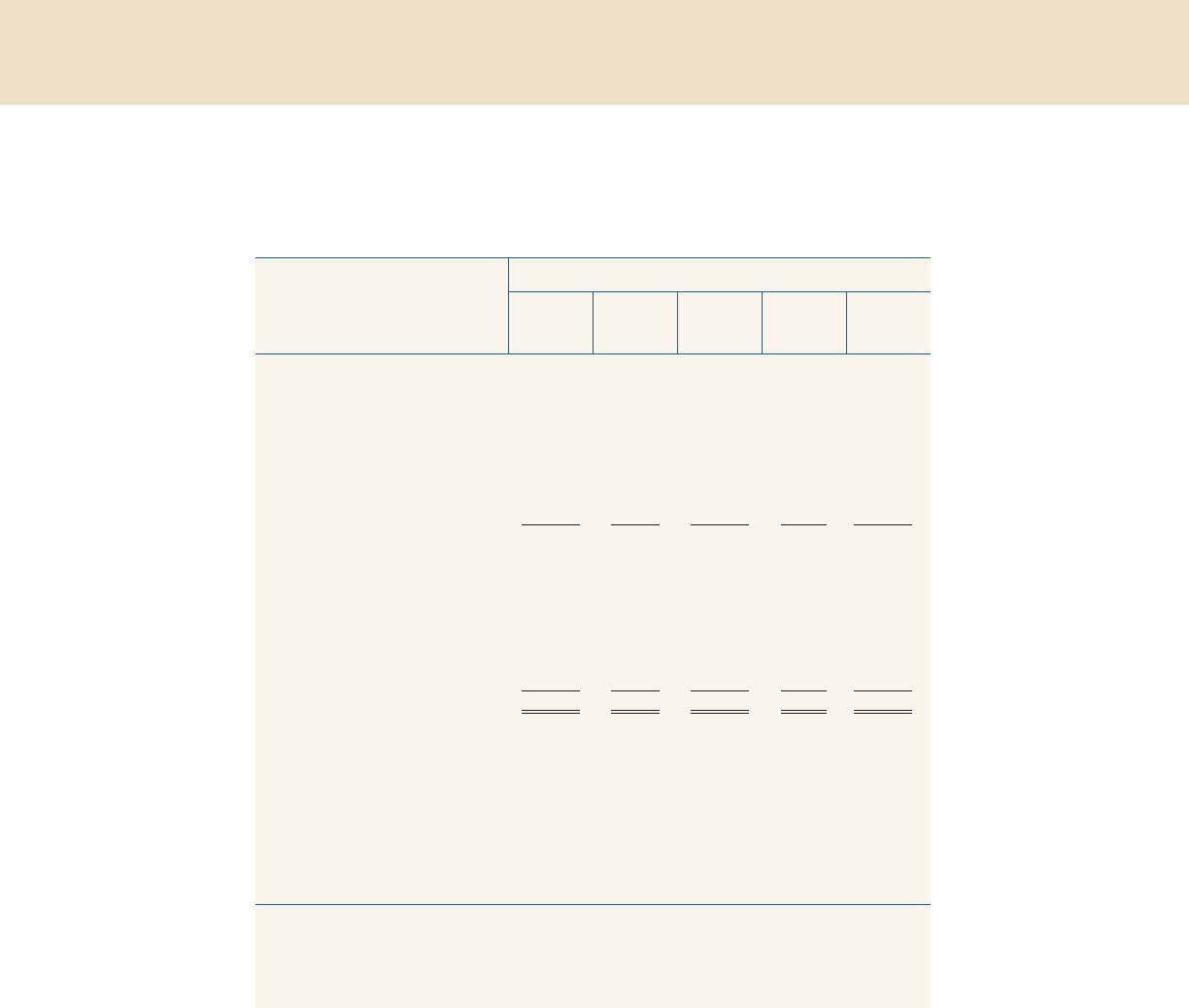

Figure 6. Change in real gross domestic product, gross

domestic income, and private domestic final purchases

4

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

Percent, annual rate

2014201320122011201020092008

H1

H2*

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic income

Private domestic final purchases

* Gross domestic income is not yet available for 2014:H2.

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

10 101st Annual Report | 2014

of corporate equities rose about 10 percent in 2014,

on top of the 30 percent gain seen in 2013. Although

the gains in house prices slowed last year—for

example, the CoreLogic national index increased only

5 percent after having risen more substantially in

2012 and 2013—these gains affected a larger share of

the population than did the gains in equities, as more

individuals own homes than own stocks (

figure 8).

Reflecting increases in home and equity prices, aggre-

gate household net wealth has risen appreciably from

its levels during the recession and its aftermath to

more than six times the value of disposable

personal income.

Coupled with low interest rates, the rise in incomes

has lowered debt payment burdens for many house-

holds. The household debt service ratio—that is, the

ratio of required principal and interest payments on

outstanding household debt to disposable personal

income—has remained at a very low level by histori-

cal standards.

. . . and increased credit availability for

consumers

Consumer credit continued to expand through late

2014, as auto and student loans have remained avail-

able even to borrowers with lower credit scores. In

addition, credit cards have become somewhat more

accessible to individuals on the lower end of the

credit spectrum, and overall credit card debt

increased moderately last year.

Consumer confidence has moved up

Consistent with the improvement in the labor market

and the fall in energy prices, indicators of consumer

sentiment moved up noticeably in the second half of

last year. The University of Michigan Surveys of

Consumers’ index of consumer sentiment—which

incorporates households’ views about their own

financial situations as well as broader economic con-

ditions—has moved up strongly, on net, in recent

months and is now close to its long-run average. The

Michigan survey’s measure of households’ expecta-

tions of real income changes in the year ahead has

also continued to trend up over the past several

months, perhaps reflecting the fall in gasoline prices.

However, this measure remains substantially below

its historical average and suggests a more guarded

outlook than the headline sentiment index.

However, the pace of homebuilding has improved

only slowly

After advancing reasonably well in 2012 and early

2013, the recovery in residential construction activity

has slowed markedly. Single-family housing starts

only edged up in 2014, and multifamily construction

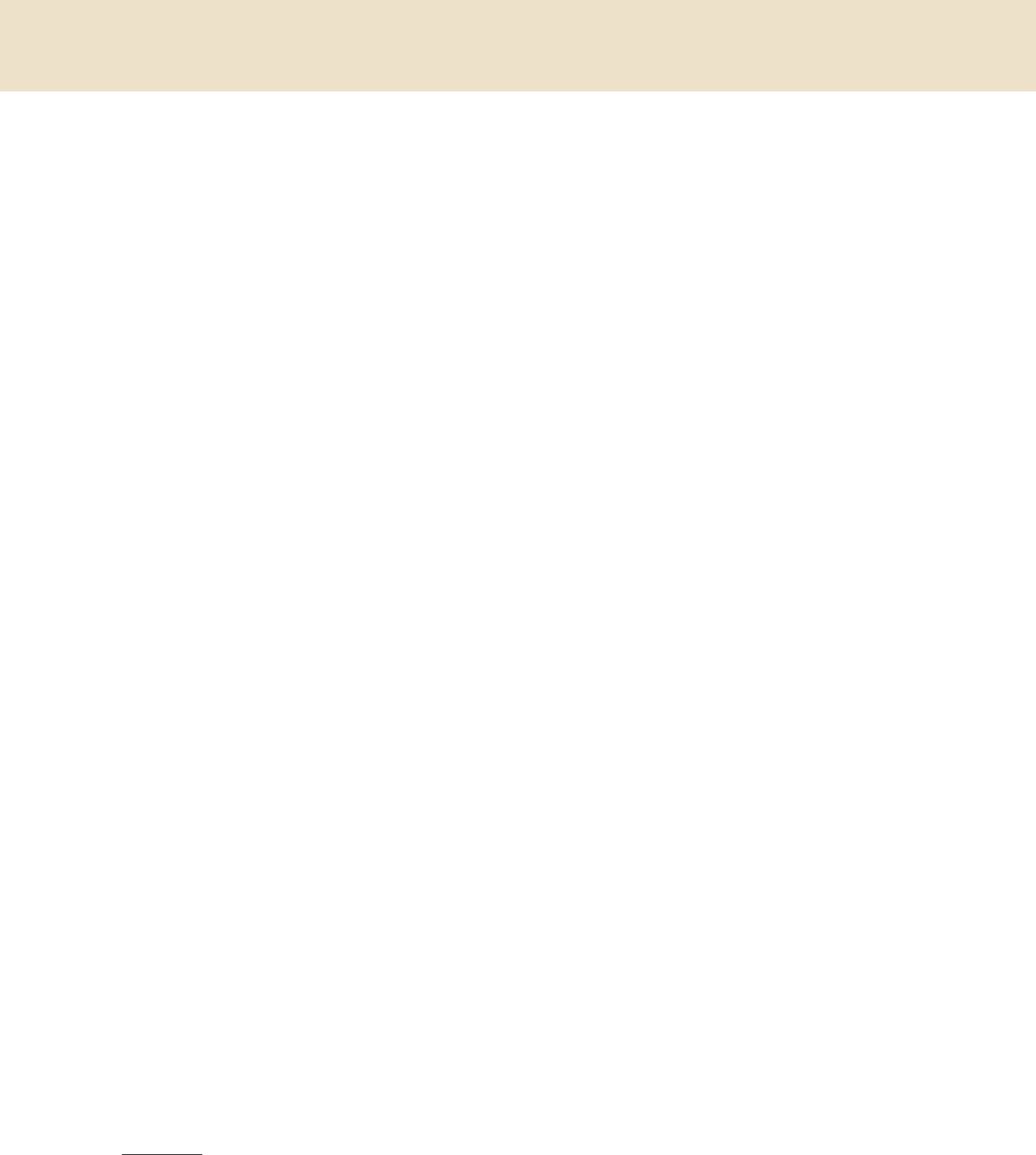

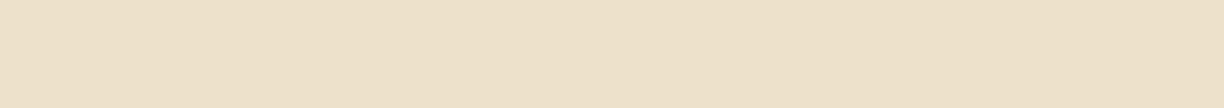

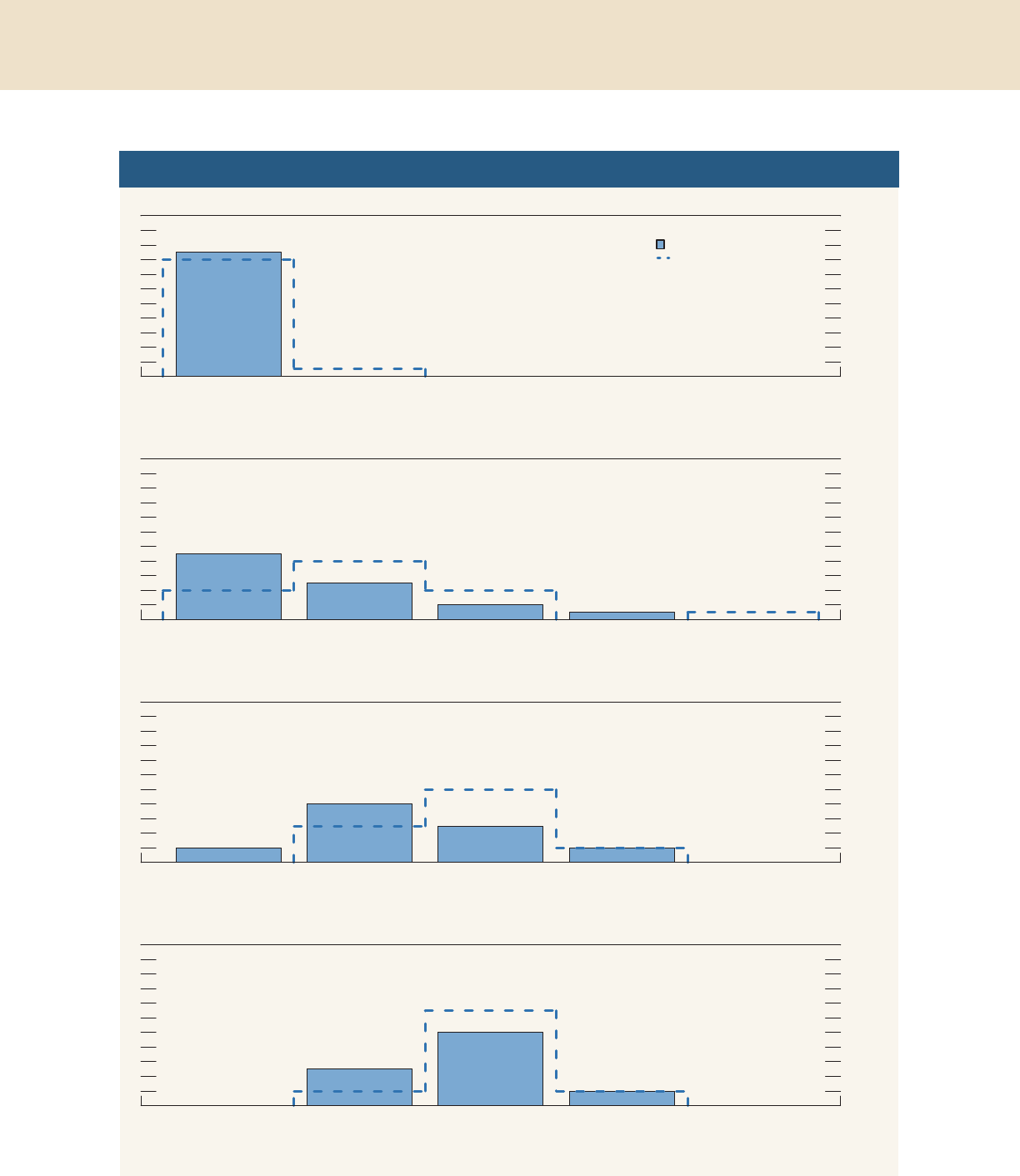

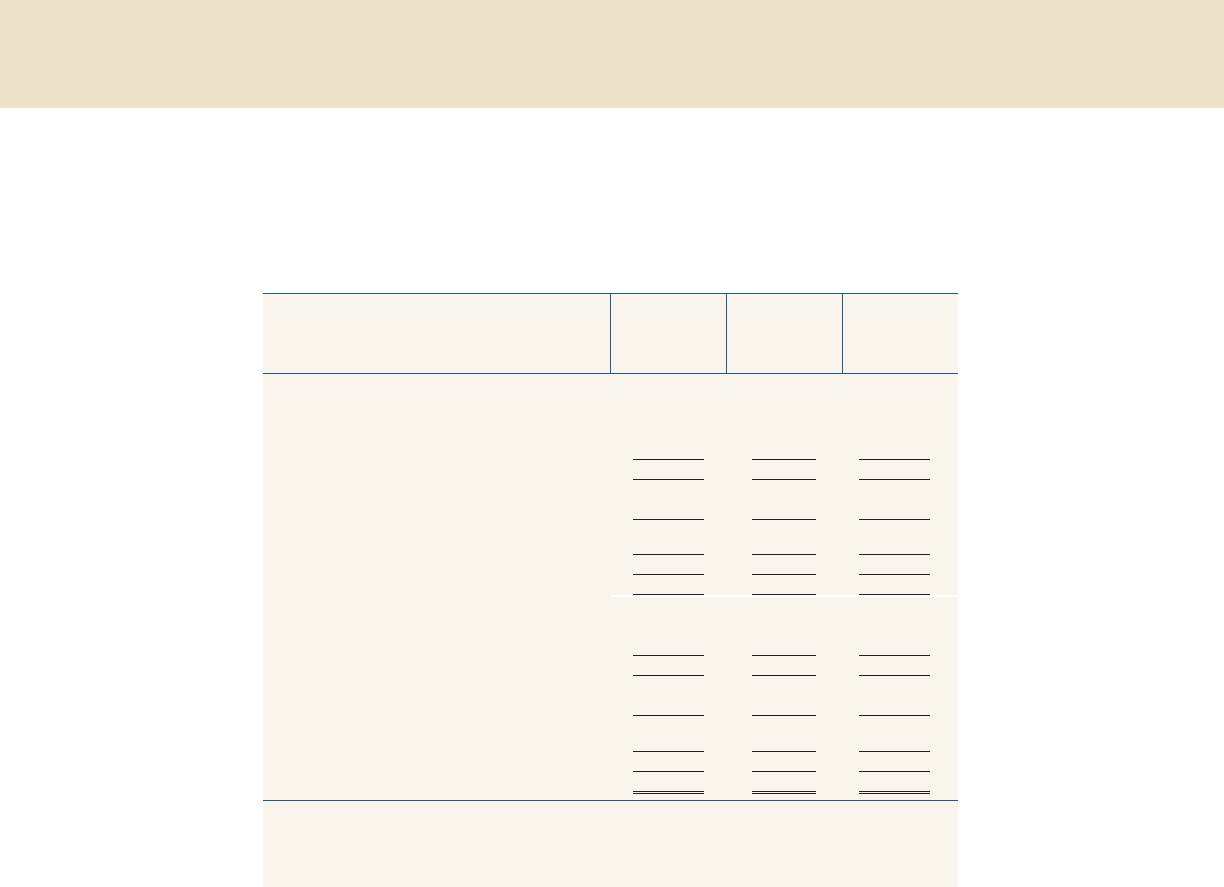

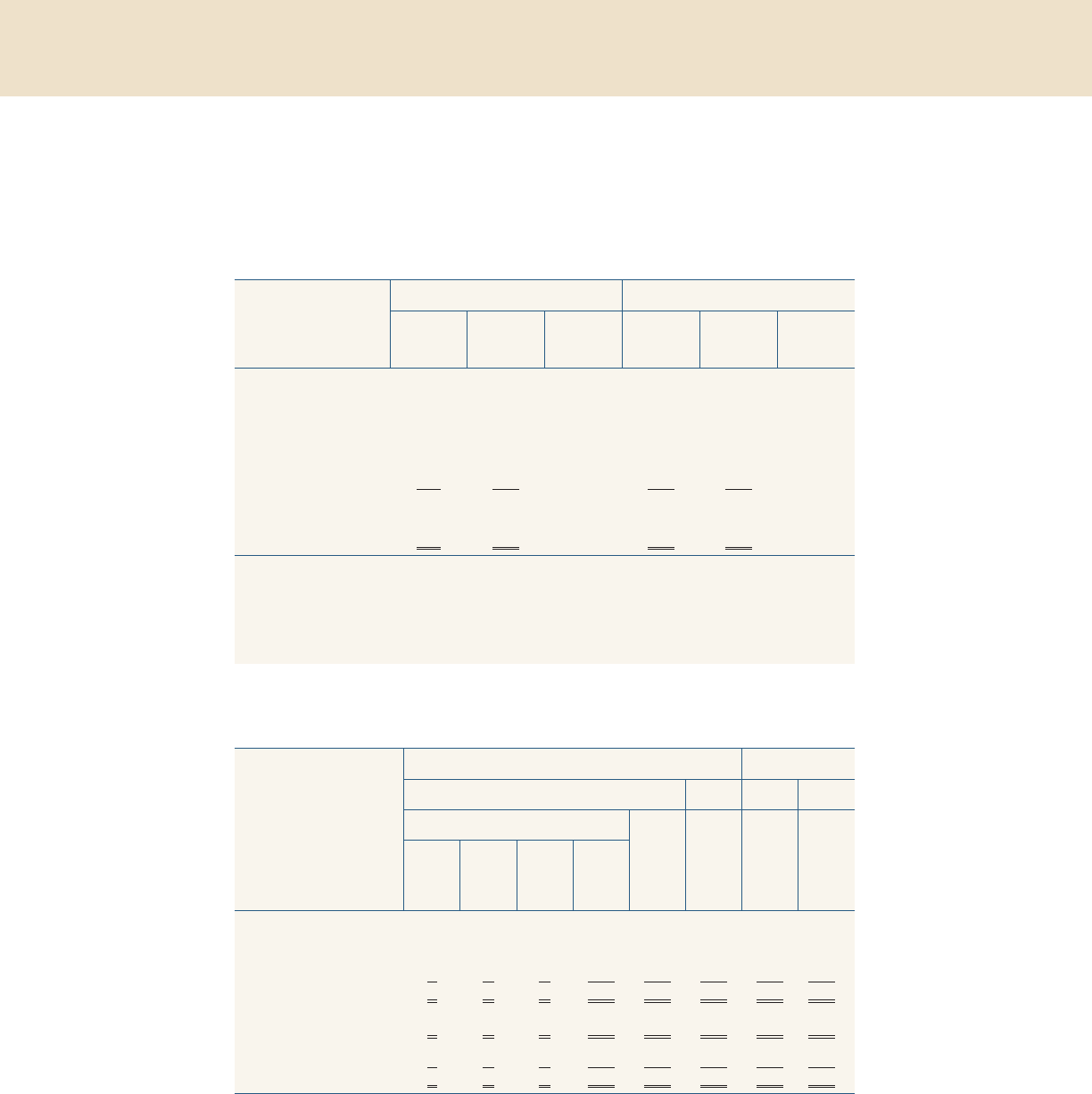

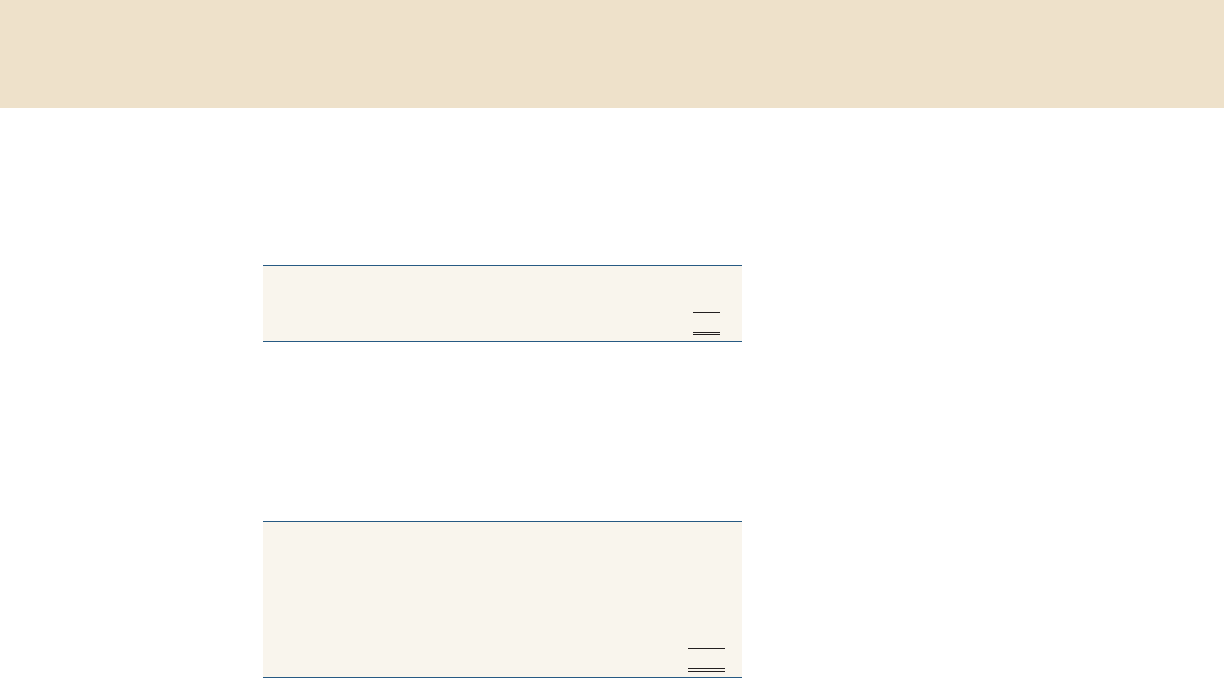

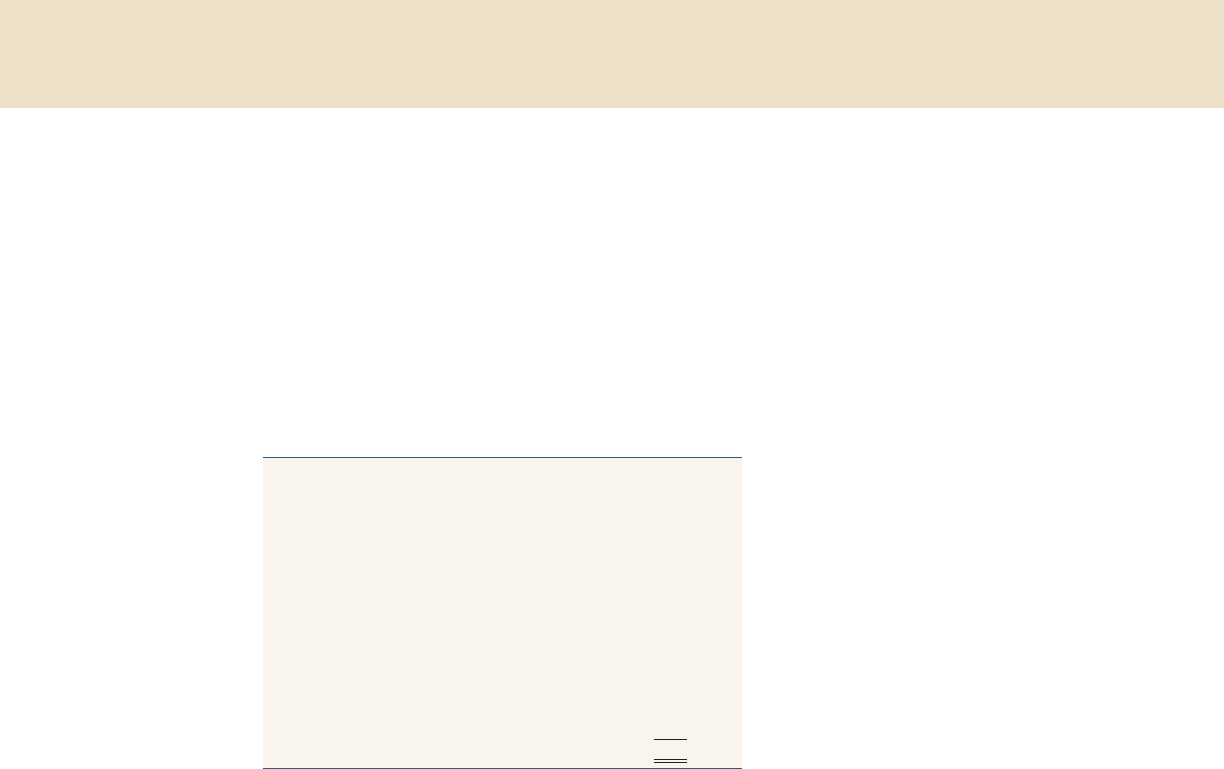

Figure 7. Change in real personal consumption

expenditures and disposable personal income

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percent, annual rate

2014201320122011201020092008

H1

H2

Personal consumption expenditures

Disposable personal income

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

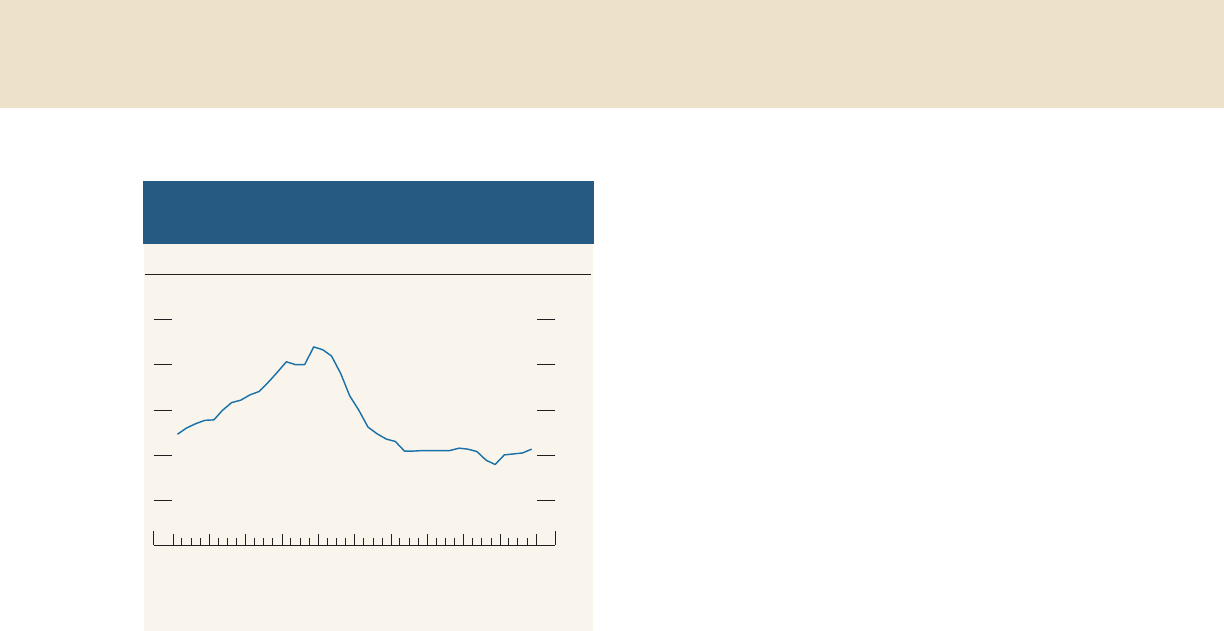

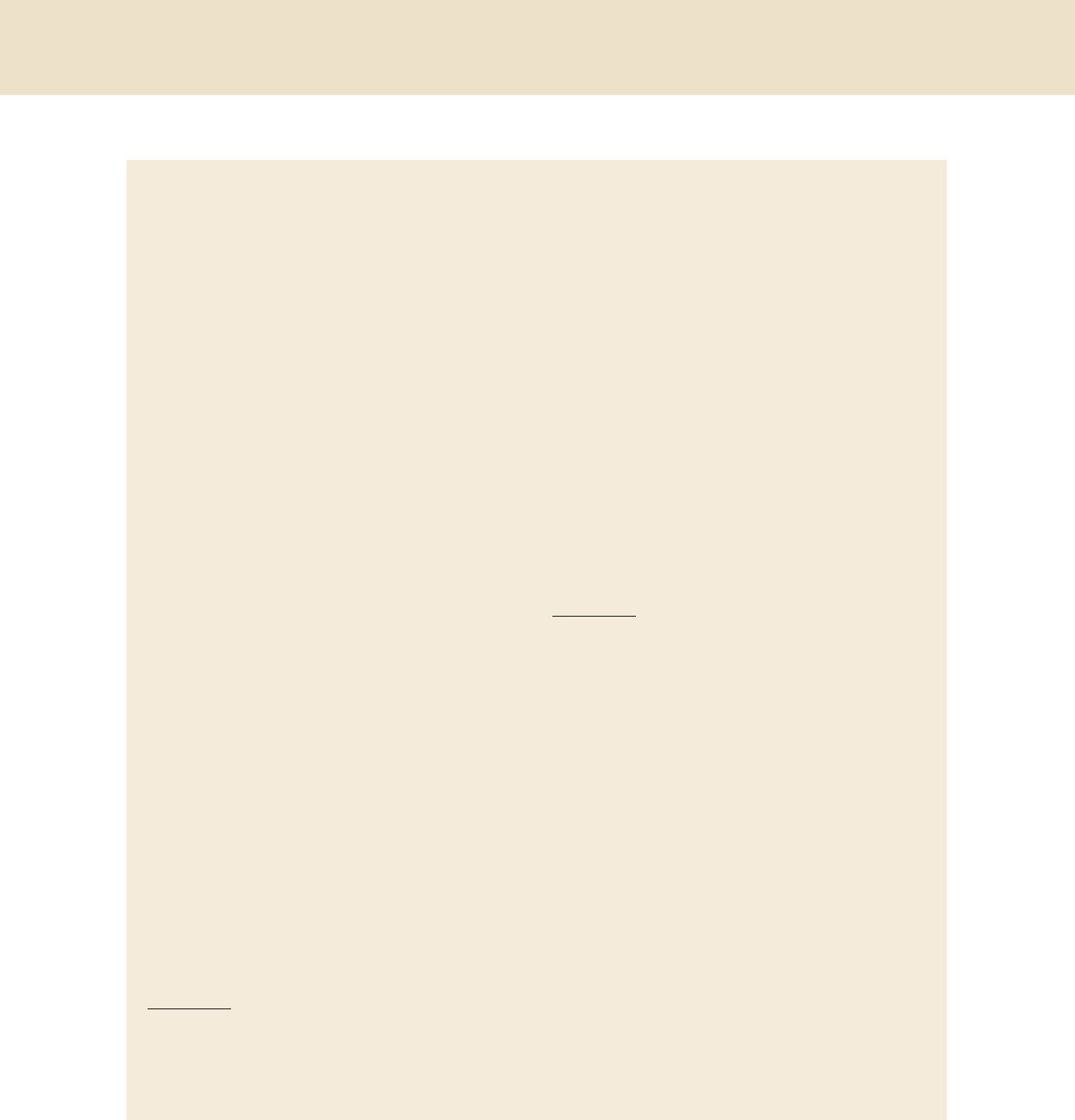

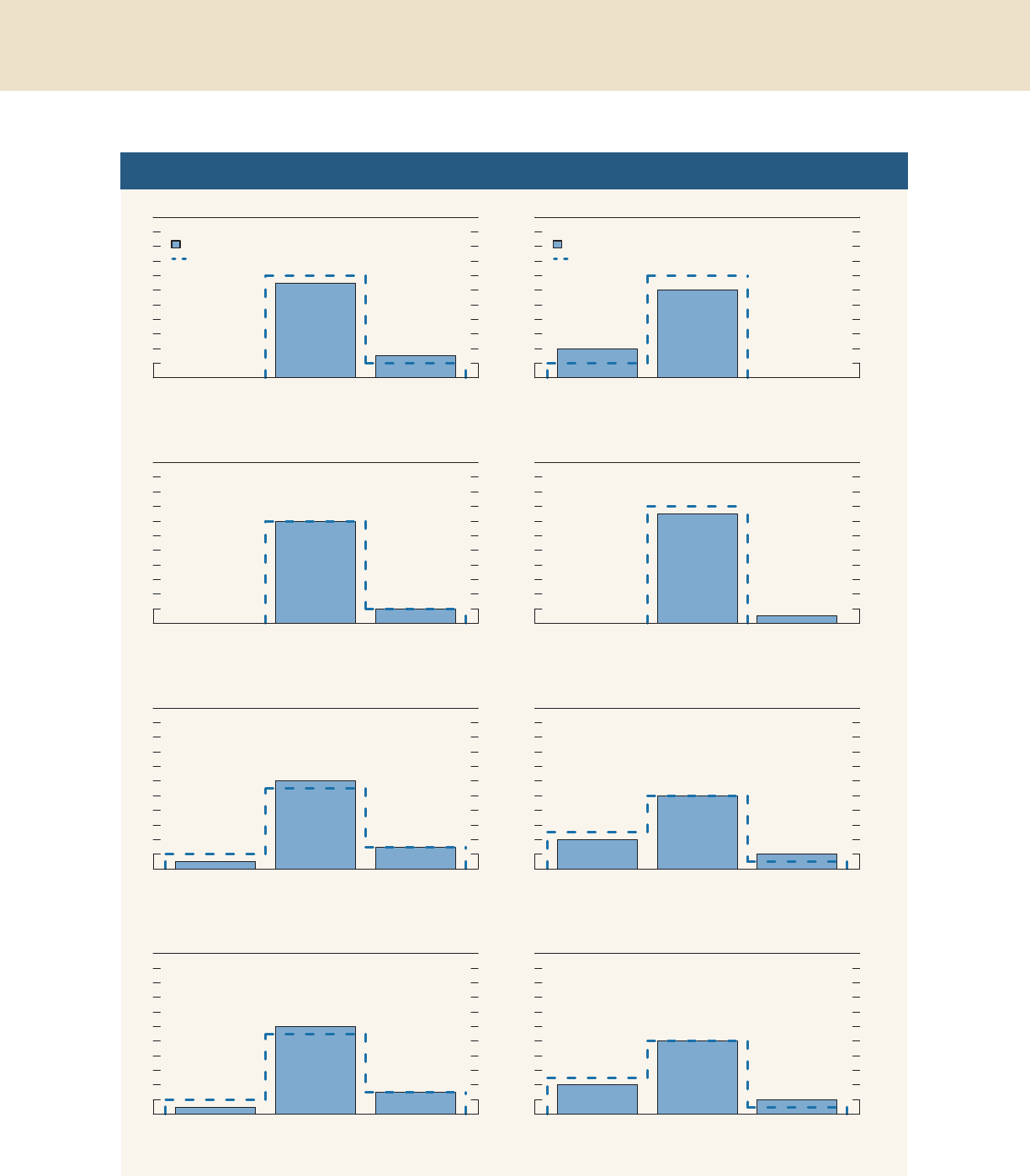

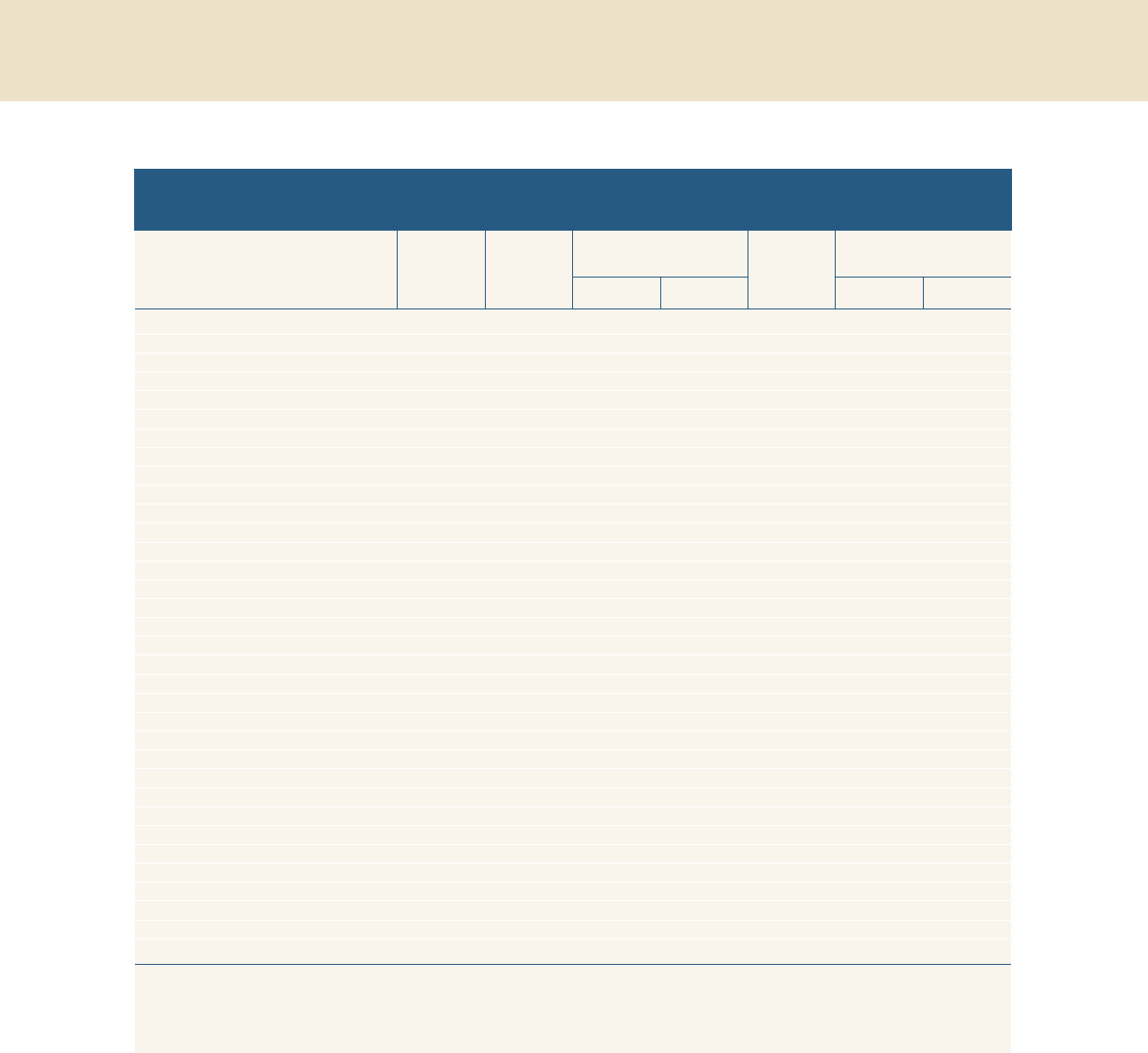

Figure 8. Prices of existing single-family houses

CoreLogic

price index

S&P/Case-Shiller

national index

70

80

90

100

Peak = 100

2014201120082005

Monthly

Zillow

index

Note: The data for the Zillow and S&P/Case-Shiller indexes extend through

November 2014. The data for the CoreLogic index extend through Decem-

ber 2014. Each index has been normalized so that its peak is 100. The CoreLogic

price index includes purchase transactions only and is adjusted by Federal

Reserve Board staff. The S&P/Case-Shiller index reflects all arm’s-length sales

transactions nationwide.

Source: The S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index (“Index”) is a prod-

uct of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates and has been licensed for

use by the Board. Copyright © 2015 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a subsidiary of

the McGraw Hill Financial Inc., and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Redistribu-

tion, reproduction and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without

written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more information on any of

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices please visit www.spdji.com. S&P® is a reg-

istered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC and Dow Jones®

is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither S&P

Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their affiliates nor

their third party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or

implied, as to the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class or

market sector that it purports to represent and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices

LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their affiliates nor their third party licen-

sors shall have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index

or the data included therein.

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments 11

activity was also little changed (figure 9). And sales

of both new and existing homes were flat, on net, last

year. In all, real residential investment rose only

2½ percent in 2014, and it remains well below its pre-

recession peak. The weak recovery in construction

likely relates to the rate of household formation,

which, notwithstanding tentative signs of a recent

pickup, has generally stayed very low despite the

improvement in the labor market.

Lending policies for home purchases remained tight

overall, although there are some indications that

mortgage credit has started to become more widely

accessible. Over the course of 2014, the fraction of

home-purchase mortgages issued to borrowers with

credit scores on the lower end of the spectrum edged

up. Additionally, in the Senior Loan Officer Opinion

Survey on Bank Lending Practices (SLOOS), several

large banks reported having eased lending standards

on prime home-purchase loans in the third and

fourth quarters of last year.

2

In January, the Federal

Housing Administration reduced its mortgage insur-

ance premiums by about one-third of the level that

had prevailed during the past four years—a step that

may lower the cost of credit for households with

small down payments and low credit scores. Even so,

mortgages have remained difficult to obtain for many

households.

Meanwhile, for borrowers who can qualify for a

mortgage, the cost of credit is low. After rising appre-

ciably around mid-2013, mortgage interest rates have

since retraced much of those increases. The 30-year

fixed mortgage rate declined roughly 60 basis points

in 2014, and it has edged down further, on net, this

year to a level not far from its all-time low in 2012.

Likely related to the most recent decline in mortgage

rates, refinancing activity rose modestly in January.

Overall business investment has moved up, but

investment in the energy sector is starting to be

affected by the drop in oil prices

Business fixed investment rose at an annual rate of

5¼ percent in the second half of 2014, close to the

rate of increase seen in the f irst half. Spending on

E&I capital rose at an annual rate of about 6 percent,

while spending on nonresidential structures moved

up about 4 percent (

figure 10). Business investment

has been supported by strengthening final demand as

well as by low interest rates and generally accommo-

dative financial conditions. Regarding nonresidential

structures, vacancy rates for existing properties have

been declining, and financing conditions for new

construction have eased further—both factors that

bode well for future construction. More recently,

however, the steep decline in the number of drilling

rigs in operation suggests that a sharp falloff in the

drilling and mining component of investment in non-

residential structures may be under way.

Corporate financing conditions were generally

favorable

The financial condition of large nonfinancial firms

generally remained solid in the second half of last

year; profitability stayed high, and default rates on

nonfinancial corporate bonds were generally very

low. Nonfinancial firms have continued to raise funds

2

The SLOOS is available on the Board’s website at www

.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/snloansurvey

.

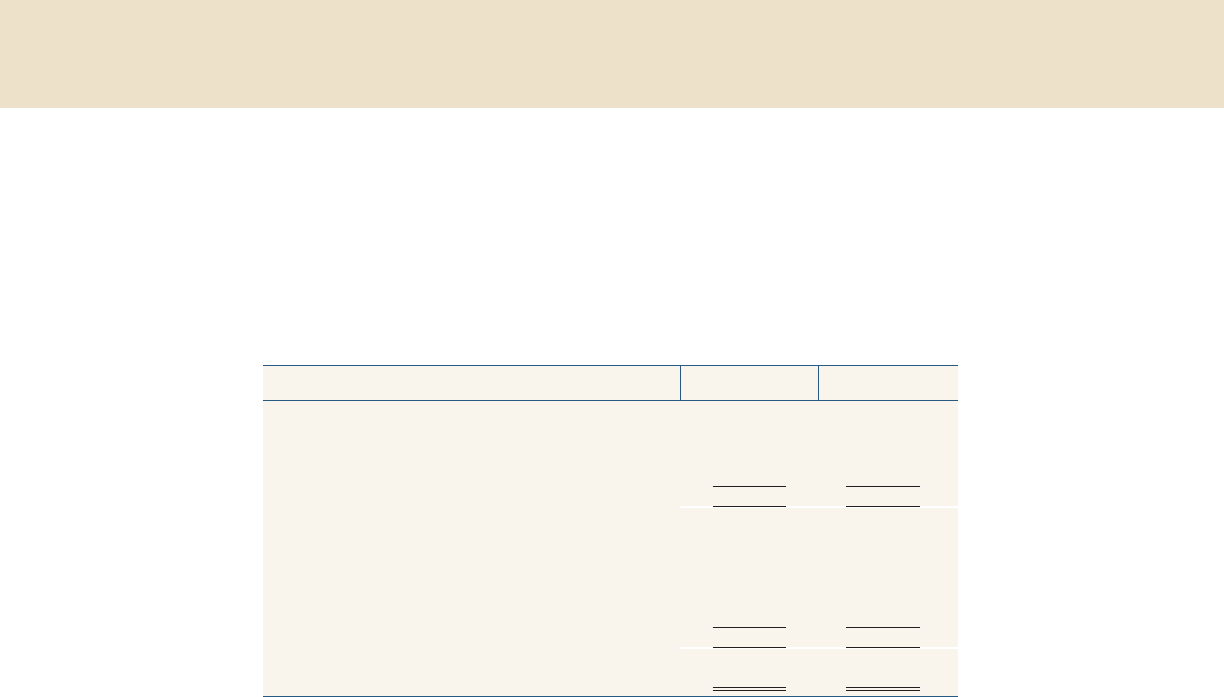

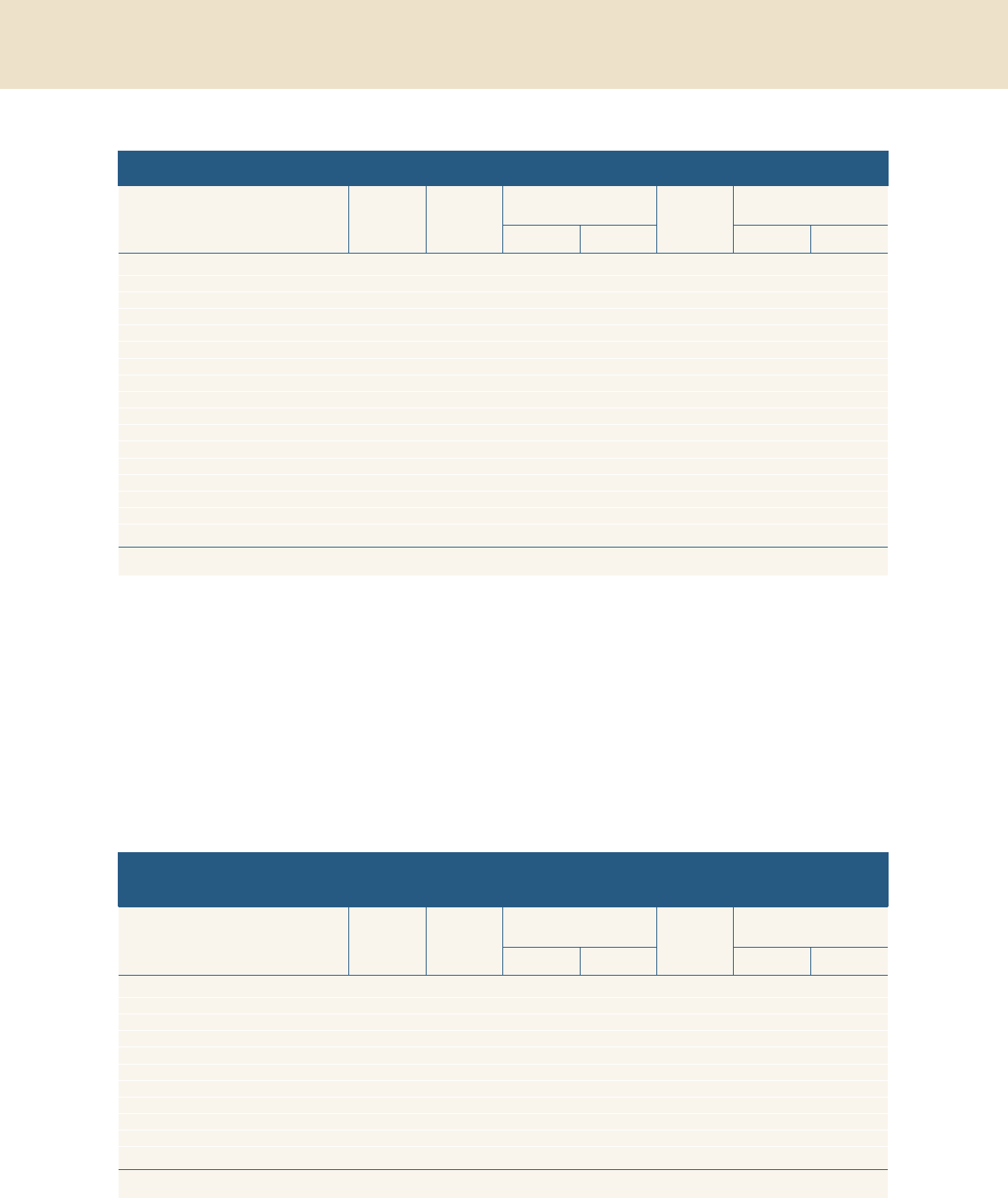

Figure 9. Private housing starts and permits

Multifamily starts

Single-family

permits

.2

.6

1.0

1.4

1.8

2.2

Millions of units, annual rate

20152013201120092007200520032001

Monthly

Single-family starts

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

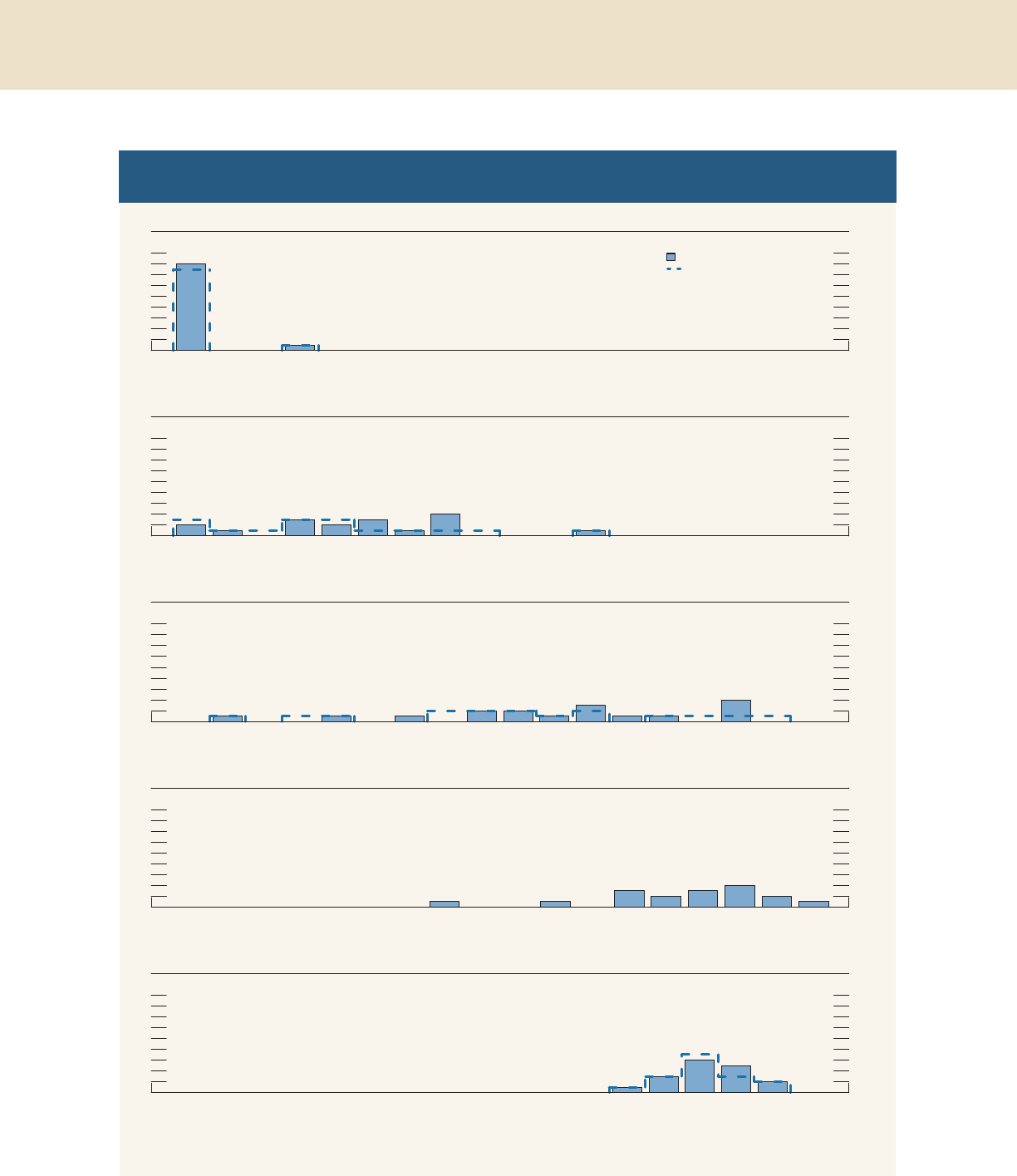

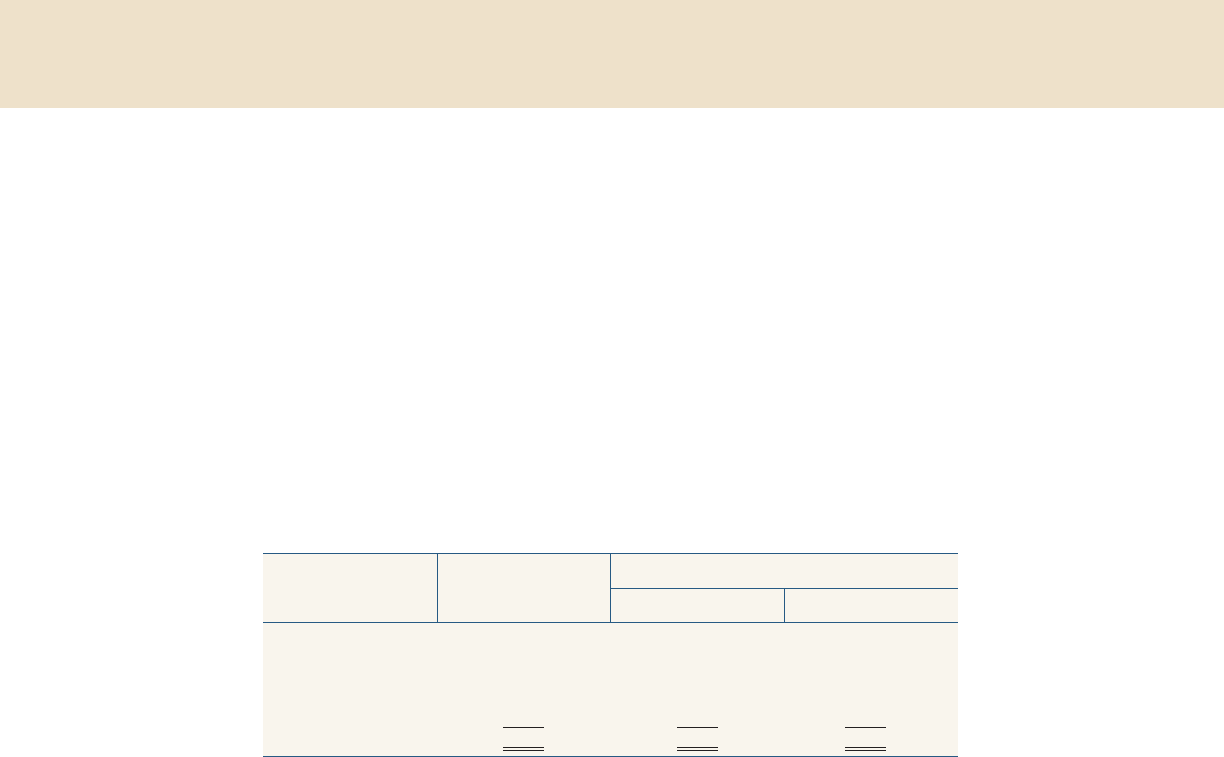

Figure 10. Change in real business fixed investment

30

20

10

+

_

0

10

20

30

Percent, annual rate

20142013201220112010200920082007

H1 H2

Structures

Equipment and intangible capital

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

12 101st Annual Report | 2014

through capital markets at a robust pace, given sturdy

corporate credit quality, historically low interest rates

on corporate bonds, and highly accommodative lend-

ing conditions for most firms. Bond issuance by

investment-grade nonfinancial firms, and syndicated

lending to those fir ms, have both been particularly

strong. However, speculative-grade issuance in those

markets, which had remained elevated for most of

2014, diminished late in the year, because volatility

increased and spreads widened and perhaps also

because of greater scrutiny by regulators of syndi-

cated leveraged loans with weaker credit quality and

lower repayment capacity.

Credit also was readily available to most bank-

dependent businesses. According to the October 2014

and January 2015 SLOOS reports, banks generally

continued to ease price and nonprice terms on com-

mercial and industrial (C&I) loans to firms of all

sizes in the second half of 2014. That said, in the

fourth quarter, several banks reported having tight-

ened lending policies for oil and gas firms or, more

broadly, in response to legislative, supervisory, or

accounting changes. In addition, although overall

C&I loans on banks’ books registered substantial

increases in the second half of 2014, loans to busi-

nesses in amounts of $1 million or less—a proxy for

lending to small businesses—increased only modestly.

The weak growth in these small loans appears largely

due to sluggish demand; however, bank lending stan-

dards to small businesses are still reportedly some-

what tighter than the midpoint of their range over

the past decade despite considerable loosening over

the past few years.

Net exports held down second-half real GDP

growth slightly

Exports increased at a modest pace in the second half

of 2014, held back by lackluster growth abroad as

well as the appreciation of the dollar. Import growth

was also relatively subdued, despite the impetus from

the stronger dollar, and was well below the pace

observed in the first half (

figure 11). All told, real net

trade was a slight drag on real GDP growth in the

second half of 2014.

The current account deficit was little changed in the

third quarter of 2014 and, at 2¼ percent of nominal

GDP, was near its narrowest reading since the late

1990s. The current account deficit in the first three

quarters of 2014 was financed mainly by purchases

of Treasury and corporate securities by foreign pri-

vate investors. In contrast, the pace of foreign official

purchases in the first three quarters of the year was

the slowest in more than a decade, reflecting a signifi-

cant slowdown in reserve accumulation by emerging

market economies (EMEs).

Federal fiscal policy was less of a drag

on GDP . . .

Fiscal policy at the federal level had been a factor

restraining GDP growth for several years, especially

in 2013. In 2014, however, the contractionary effects

of tax and spending changes eased appreciably as the

restraining effects of the 2013 tax increases abated

and there was a slowing in the declines in federal pur-

chases due to sequestration and the Budget Control

Act of 2011 (

figure 12). Moreover, some of the over-

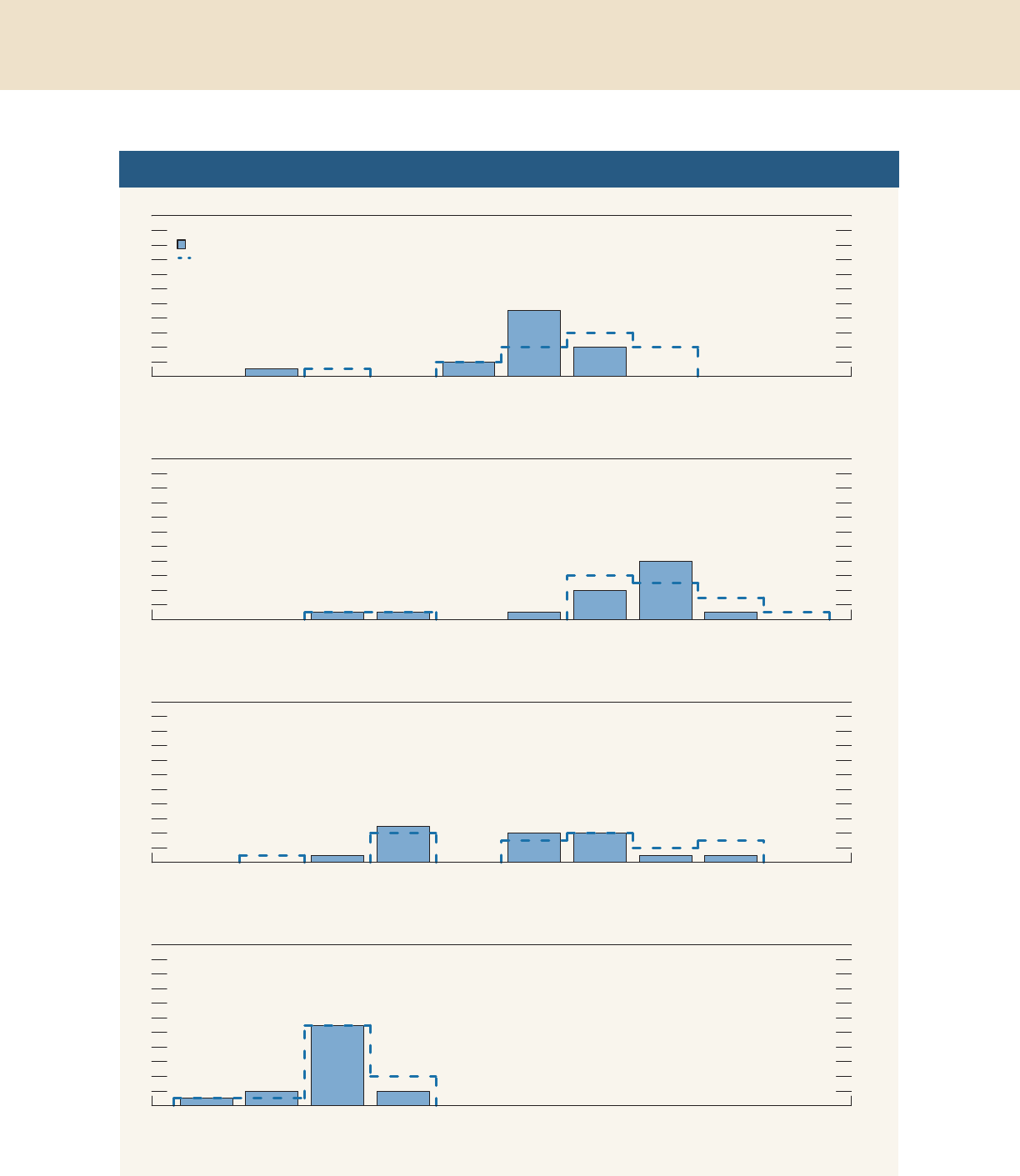

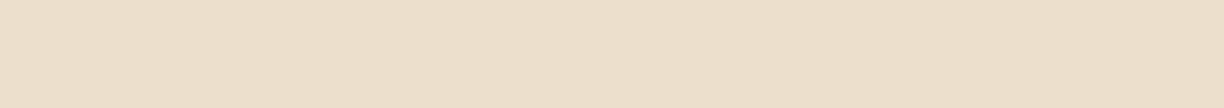

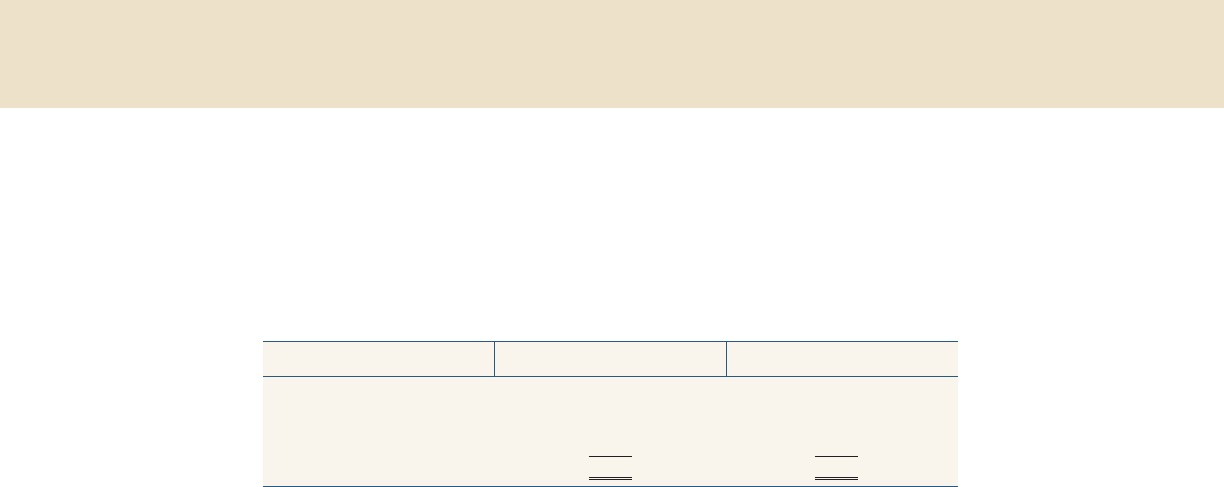

Figure 11. Change in real imports and exports of goods and

services

6

3

+

_

0

3

6

9

12

Percent, annual rate

2014201320122011201020092008

H1

H2

Imports

Exports

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

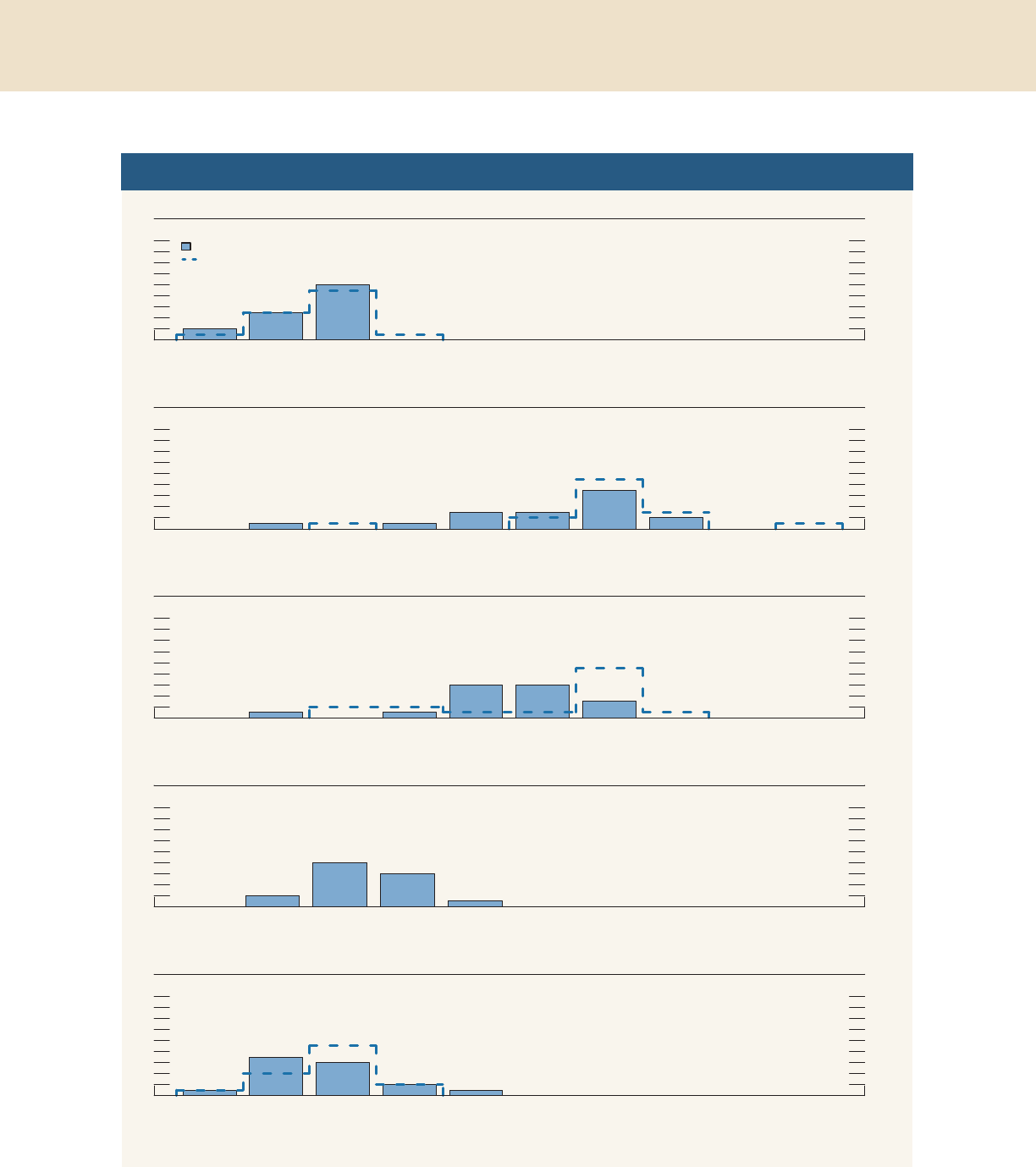

Figure 12. Change in real government expenditures on

consumption and investment

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

6

9

Percent, annual rate

2014201320122011201020092008

H1 H2

Federal

State and local

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments 13

all drag on demand was offset in 2014 by an increase

in transfers resulting from the Affordable Care Act.

The federal unified deficit narrowed further last year,

reflecting both the previous years’ spending cuts and

an increase in tax receipts resulting from the ongoing

economic expansion. The budget deficit was 2¾ per-

cent of GDP for fiscal year 2014, and the Congres-

sional Budget Office projects that it will be about

2½ percent in 2015. As a result, overall federal debt

held by the public stabilized as a share of GDP in

2014, albeit at a relatively high level.

. . . and state and local government expenditures

are also turning up

The expansion of economic activity has also led to

continued slow improvements in the fiscal position of

most state and local governments. Consistent with

improving finances, states and localities expanded

employment rolls in 2014. Furthermore, state and

local expenditures on construction projects rose a

touch last year following several years of declines.

Financial Developments

The expected path for the federal funds rate

flattened

Market participants seemed to judge the incoming

domestic economic data since the middle of last year,

especially the employment reports, as supporting

expectations for continued economic expansion in

the United States; however, concerns about the for-

eign economic outlook weighed on investor senti-

ment. On balance, market-based measures of the

expected (or mean) path of the federal funds rate

through late 2017 have flattened, but the expected

timing of the initial increase in the federal funds rate

from its current target range was about unchanged.

In addition, according to the results of the most

recent Survey of Primary Dealers and the Survey of

Market Participants, both conducted by the Federal

Reserve Bank of New York just prior to the January

FOMC meeting, respondents judged that the initial

increase in the target federal funds rate was most

likely to occur around mid-2015, little changed from

the results of those surveys from last June.

3

Mean-

while, in part because the passage of time brought

the anticipated date of the initial increase in the fed-

eral funds rate closer, measures of policy rate uncer-

tainty based on interest rate derivatives edged higher,

on net, from their mid-2014 levels.

Longer-term Treasury yields and other sovereign

benchmark yields declined

Yields on longer-term Treasury securities have con-

tinued to move down since the middle of last year on

net (

figure 13). In particular, the yields on 10- and

30-year nominal Treasury securities declined about

40 basis points and 60 basis points, respectively, from

their levels at the end of June 2014. The decreases in

longer-term yields were driven especially by reduc-

tions in longer-horizon forward rates. For example,

the 5-year forward rate 5 years ahead dropped about

80 basis points over the same period. Long-term

benchmark sovereign yields in advanced foreign

economies (AFEs) have also moved down signifi-

cantly in response to disappointing growth and very

low and declining rates of inflation in a number of

foreign countries as well as the associated actual and

anticipated changes in monetary policy abroad.

The declines in longer-term Treasury yields and long-

horizon forward rates seem to largely reflect reduc-

tions in term premiums—the extra return investors

expect to obtain from holding longer-term securities

as opposed to holding and rolling over a sequence of

short-term securities for the same period. Market

participants pointed to several factors that may help

to explain the reduction in term premiums. First,

very low and declining AFE yields and safe-haven

flows associated with the deterioration in the foreign

economic outlook likely have increased demand for

Treasury securities. Second, the weaker foreign eco-

3

The results of the Survey of Primary Dealers and of the Survey

of Market Participants are available on the Federal Reserve

Bank of New York’s website at

www.newyorkfed.org/markets/

primarydealer_survey_questions.html

and www.newyorkfed.org/

markets/survey_market_participants.html

, respectively.

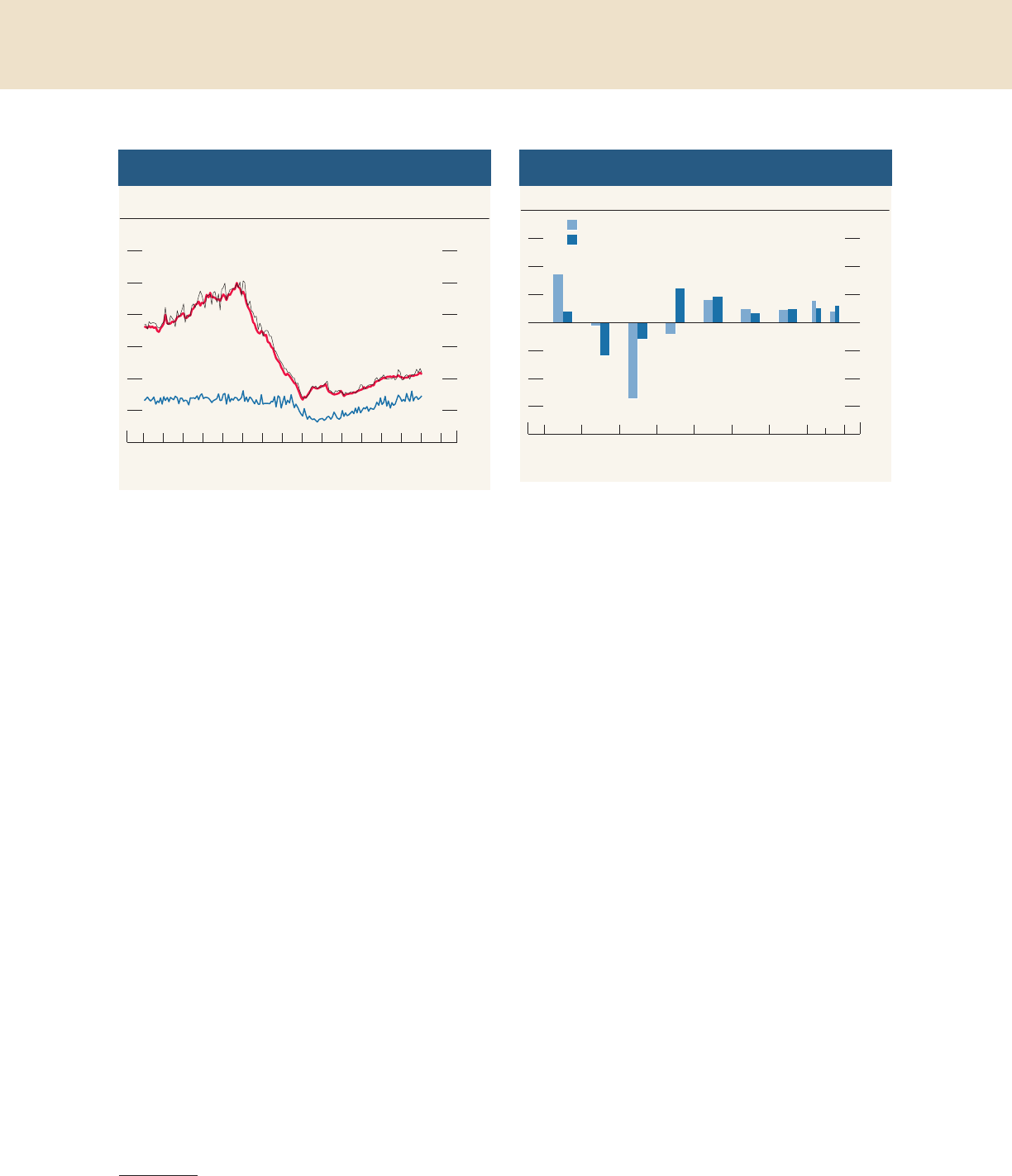

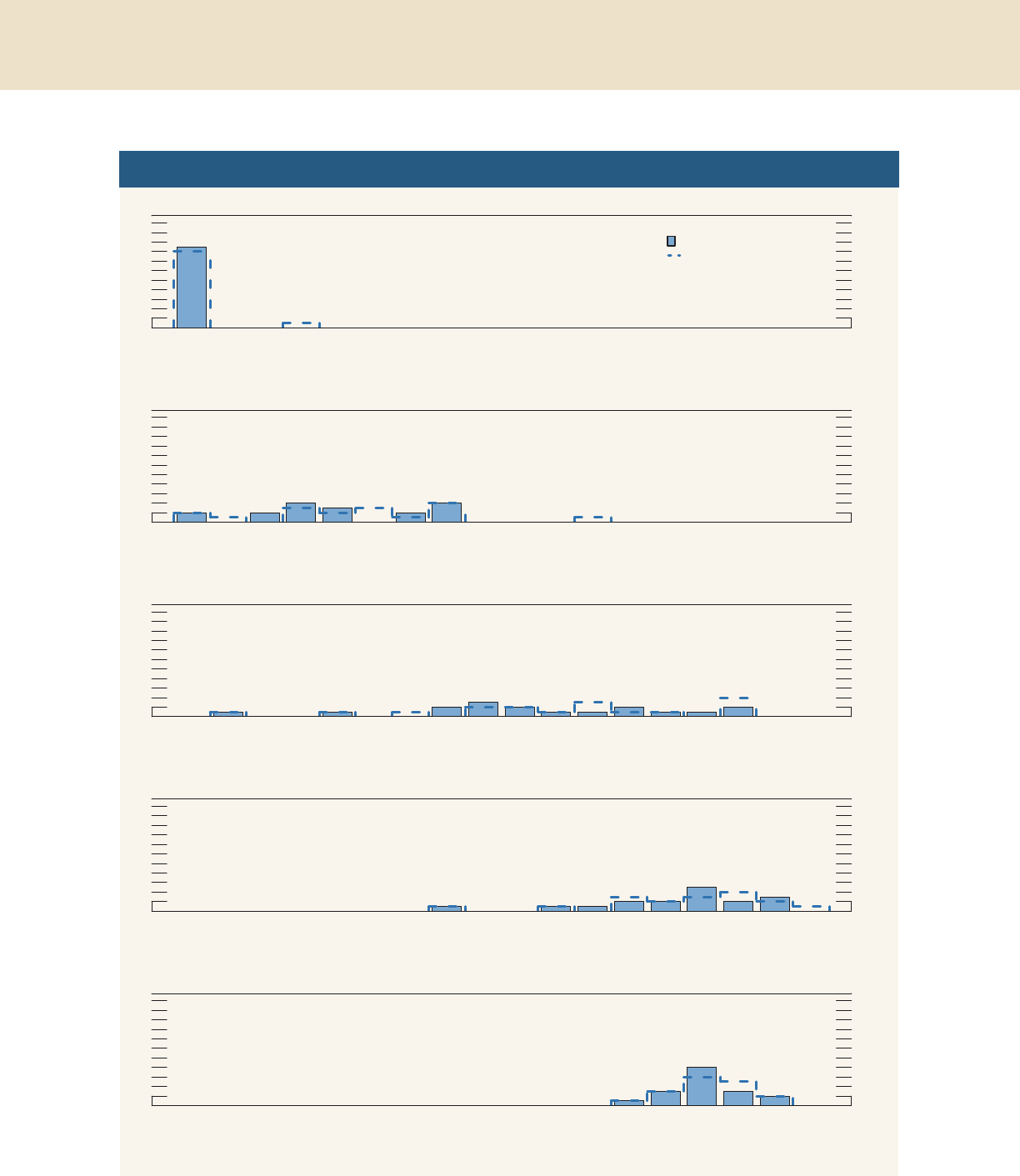

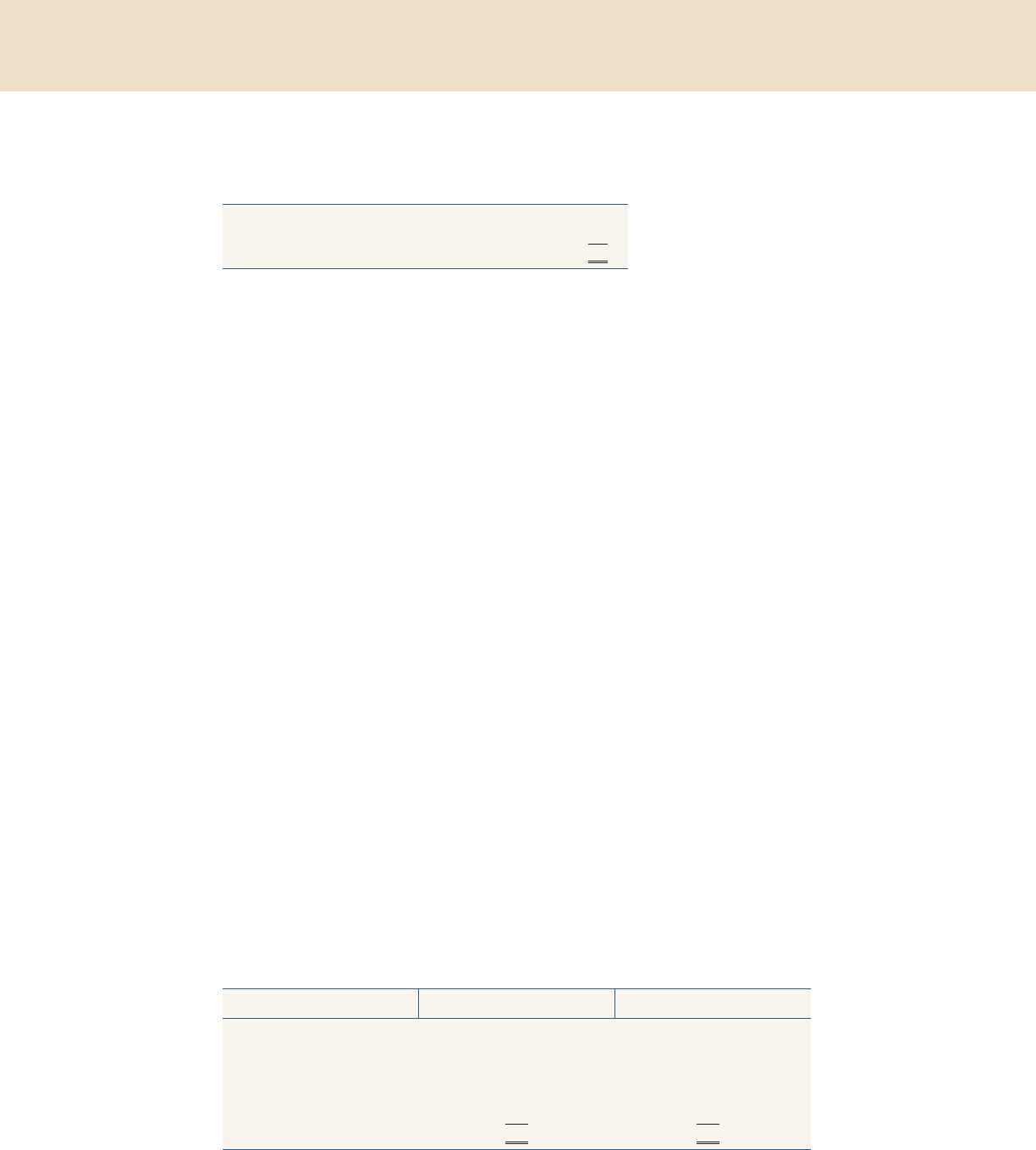

Figure 13. Yields on nominal Treasury securities

5-year

30-year

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Percent

20152013201120092007200520032001

Daily

10-year

Note: The Treasury ceased publication of the 30-year constant maturity series on

February 18, 2002, and resumed that series on February 9, 2006.

Source: Department of the Treasury.

14 101st Annual Report | 2014

nomic outlook coupled with the steep decline in oil

prices may have led investors to put higher odds on

scenarios in which U.S. inflation remains quite low

for an extended period. Investors may see nominal

long-term Treasury securities as an especially good

hedge against such risks. Finally, market participants

may have increased the probability they attach to

outcomes in which U.S. economic growth is persis-

tently subdued. Indeed, the 5-year forward real yield

5 years ahead, obtained from yields on Treasury

Inflation-Protected Securities, has declined further,

on net, since the middle of last year and stands well

below levels commonly cited as estimates of the

longer-run real short rate.

Consistent with moves in the yields on longer-term

Treasury securities, yields on 30-year agency

mortgage-backed securities (MBS)—an important

determinant of mortgage interest rates—decreased

about 30 basis points, on balance, over the second

half of 2014 and early 2015.

Liquidity conditions in Treasury and agency MBS

markets were generally stable . . .

On balance, indicators of Treasury market function-

ing remained stable over the second half of 2014 even

as the Federal Reserve trimmed the pace of its asset

purchases and ultimately brought the purchase pro-

gram to a close at the end of October. The Treasury

market experienced a sharp drop in yields and signifi-

cantly elevated volatility on October 15, as technical

factors reportedly amplified price movements follow-

ing the release of the somewhat weaker-than-

expected September U.S. retail sales data. However,

market conditions recovered quickly and liquidity

measures, such as bid-asked spreads, have been gen-

erally stable since then. Moreover, Treasury auctions

generally continued to be well received by investors.

As in the Treasury market, liquidity conditions in the

agency MBS market were generally stable, with the

exception of mid-October. Dollar-roll-implied

financing rates for production coupon MBS—an

indicator of the scarcity of agency MBS for settle-

ment— suggested limited settlement pressures in

these markets over the second half of 2014 and

early 2015.

. . . and short-term funding markets also

continued to function well as rates moved

slightly higher overall

Conditions in short-term dollar funding markets also

remained stable during the second half of 2014 and

early 2015. Both unsecured and secured money mar-

ket rates moved modestly higher late in 2014 but

remained close to their averages since the federal

funds rate reached its effective lower bound. Unse-

cured offshore dollar funding markets generally did

not exhibit signs of stress, and the repurchase agree-

ment, or repo, market functioned smoothly with

modest year-end pressures.

Money market participants continued to focus on the

ongoing testing of the Federal Reserve’s monetary

policy tools. The offering rate in the overnight reverse

repurchase agreement (ON RRP) exercise has contin-

ued to provide a soft floor for other rates on secured

borrowing, and the term RRP testing operations that

were conducted in December and matured in early

January seemed to help alleviate year-end pressures

in money markets. For a detailed discussion of the

testing of monetary policy tools, see the box “

Addi-

tional Testing of Monetary Policy Tools

” on pages

36–37 of the February 2015 Monetary Policy Report.

Broad equity price indexes rose despite higher

volatility, while risk spreads on corporate debt

widened

Over the second half of 2014 and early 2015, broad

measures of U.S. equity prices increased further, on

balance, but stock prices for the energy sector

declined substantially, reflecting the sharp drops in

oil prices (

figure 14). Although increased concerns

about the foreign economic outlook seemed to weigh

on risk sentiment, the generally positive tone of U.S.

economic data releases as well as declining longer-

term interest rates appeared to provide support for

equity prices. Overall equity valuations by some con-

ventional measures are somewhat higher than their

historical average levels, and valuation metrics in

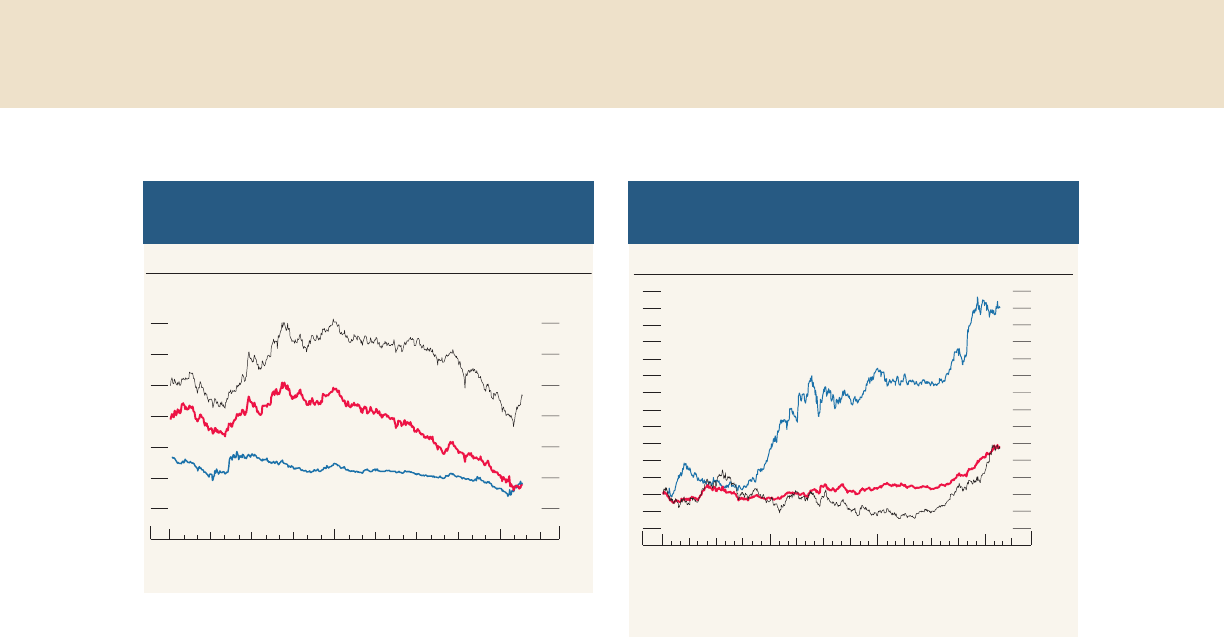

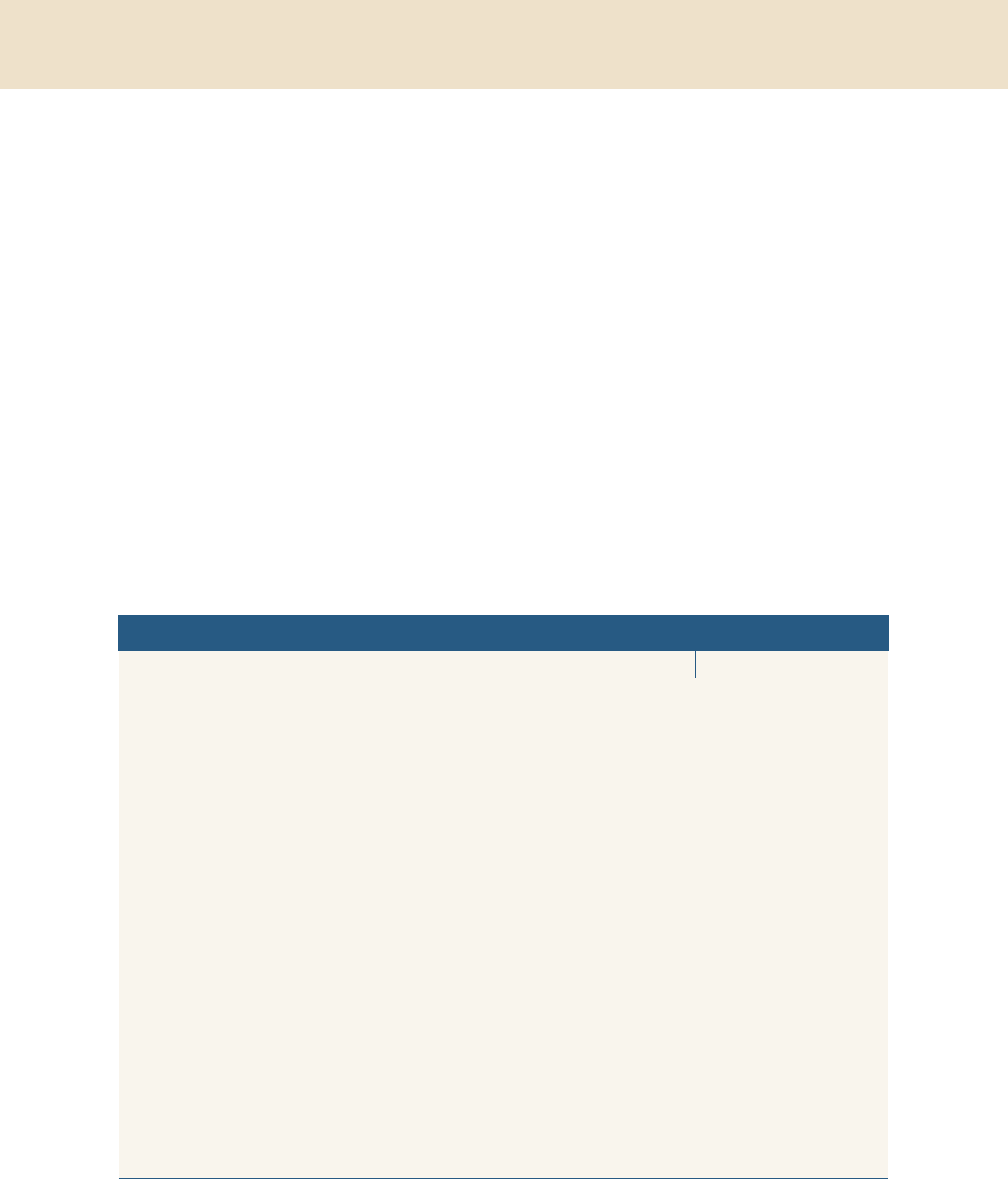

Figure 14. Equity prices

S&P 500 index

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

December 31, 2007 = 100

20152012200920062003200019971994

Daily

Dow Jones

bank index

Source: Dow Jones bank index and Standard & Poor’s 500 index via Bloomberg.

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments 15

some sectors continue to appear stretched relative to

historical norms. Implied volatility for the S&P 500

index, as calculated from options prices, increased

moderately, on net, from low levels over the summer.

Corporate credit spreads, particularly those for

speculative-grade bonds, widened from the fairly low

levels of last summer, in part because of the under-

performance of energy firms. Overall, corporate

bond spreads across the credit spectrum have been

near their historical median levels recently. For fur-

ther discussion of asset prices and other financial sta-

bility issues, see the box “

Developments Related to

Financial Stability

” on pages 24–25 of the Febru-

ary 2015 Monetary Policy Report.

Bank credit and the M2 measure of the money

stock continued to expand

Aggregate credit provided by commercial banks

increased at a solid pace in the second half of 2014

(

figure 15). The expansion in bank credit was mainly

driven by moderate loan growth coupled with contin-

ued robust expansion of banks’ holdings of U.S.

Treasury securities, which was reportedly influenced

by efforts of large banks to meet the new Basel III

Liquidity Coverage Ratio requirements. The growth

of loans on banks’ books was generally consistent

with the SLOOS reports of increased loan demand

and further easing of lending standards for many

loan categories over the second half of 2014. Mean-

while, delinquency and charge-off rates fell across

most major loan types.

Measures of bank profitability were little changed in

the second half of 2014, on net, and remained below

their historical averages. Equity prices of large

domestic bank holding companies (BHCs) have

increased moderately, on net, since the middle of last

year. Credit default swap (CDS) spreads for large

BHCs were about unchanged.

The M2 measure of the money stock has increased at

an average annualized rate of about 5½ percent since

last June, below the pace registered in the first half of

2014 and about in line with the pace of nominal

GDP. The deceleration was driven by a moderation

in the growth rate of liquid deposits in the banking

sector relative to the first half of 2014. Although

demand for currency weakened in the third quarter

of 2014 relative to the first half of the year, currency

growth has been strong since November.

Municipal bond markets functioned smoothly, but

some issuers remained strained

Credit conditions in municipal bond markets have

generally remained stable since the middle of last

year. Over that period, the MCDX—an index of

CDS spreads for a broad portfolio of municipal

bonds—and ratios of yields on 20-year general obli-

gation municipal bonds to those on longer-term

Treasury securities increased slightly.

Nevertheless, significant financial strains were still

evident for some issuers. Puerto Rico, with

speculative-grade-rated general obligation bonds,

continued to face challenges from subdued economic

performance, severe indebtedness, and other f iscal

pressures. Meanwhile, the City of Detroit emerged

from bankruptcy late in 2014 after its debt restructur-

ing plan was approved by a federal judge.

International Developments

Bond yields in the advanced foreign economies

continued to decline . . .

As noted previously, long-term sovereign yields in the

AFEs moved down further during the second half of

2014 and into early 2015 on continued low inflation

readings abroad and heightened concerns over the

strength of foreign economic growth as well as amid

substantial monetary policy accommodation (

fig-

ure 16

). German yields fell to record lows, as the

European Central Bank (ECB) implemented new

liquidity facilities, purchased covered bonds and

asset-backed securities, and announced it would

begin buying euro-area sovereign bonds. Specifically,

the ECB said that it would purchase €60 billion per

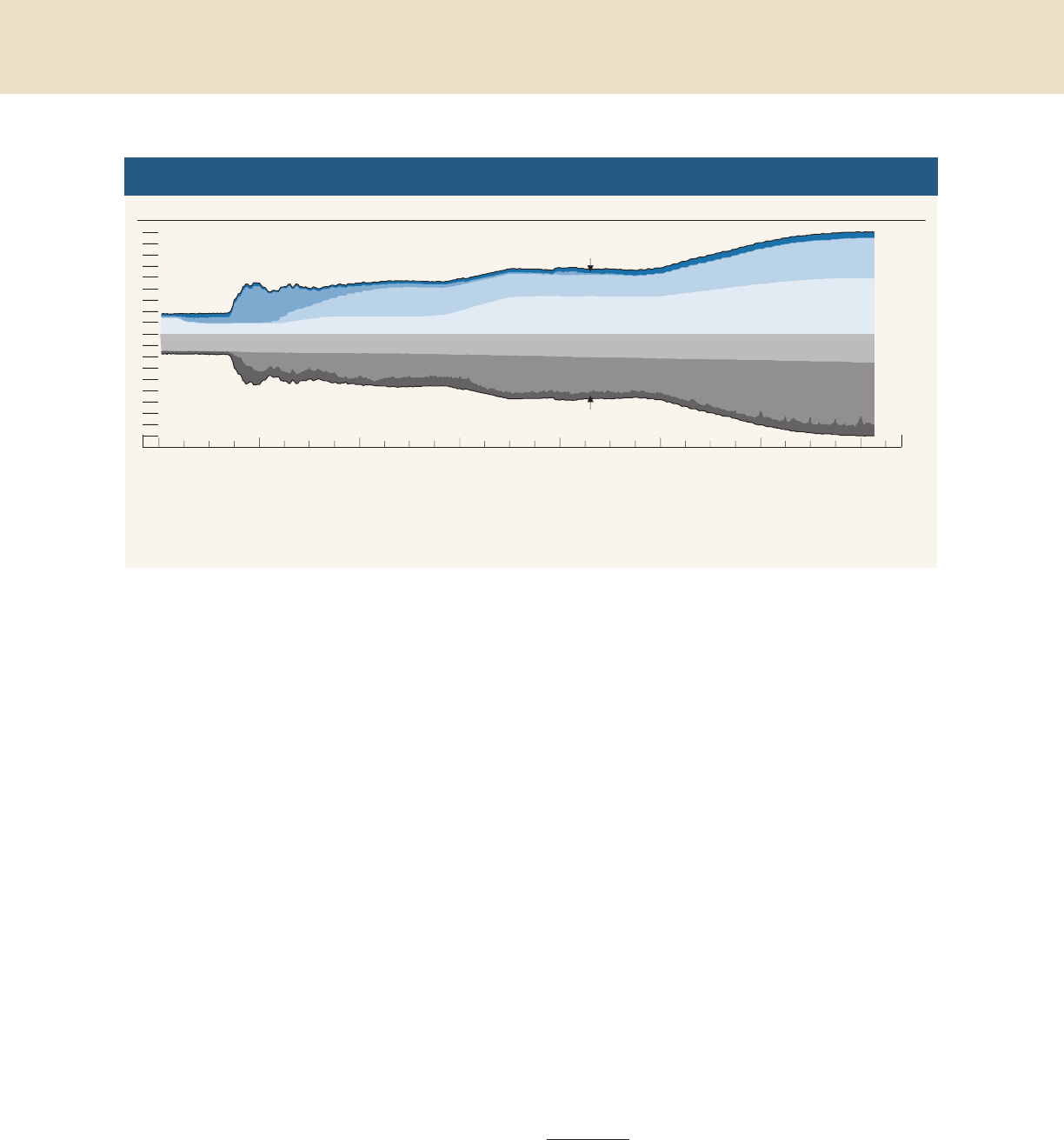

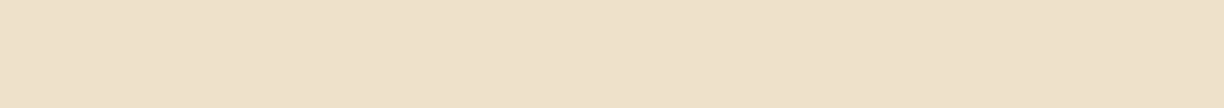

Figure 15. Ratio of total commercial bank credit to nominal

gross domestic product

55

60

65

70

75

Percent

2014201320122011201020092008200720062005

Quarterly

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release H.8, “Assets and Liabilities of

Commercial Banks in the United States”; Department of Commerce, Bureau of

Economic Analysis.

16 101st Annual Report | 2014

month of euro-area public and private bonds

through at least September 2016. Japanese yields also

declined, reflecting the expansion by the Bank of

Japan (BOJ) of its asset purchase program. In the

United Kingdom, yields fell as data showed declining

inflation and some moderation in economic growth,

although they have retraced a little of that move in

recent weeks, in part as market sentiment toward the

U.K. outlook appears to have improved somewhat.

In emerging markets, yields were mixed—falling, for

the most part, in Asia and generally rising modestly

in Latin America—as CDS spreads widened amid

growing credit concerns, particularly in some oil-

exporting countries.

. . . while the dollar has strengthened markedly

The broad nominal value of the dollar has increased

markedly since the middle of 2014, with the U.S. dol-

lar appreciating against almost all currencies (

fig-

ure 17

). The increase in the value of the dollar was

largely driven by additional monetary easing abroad

and rising concerns about foreign growth—forces

similar to those that drove benchmark yields

lower—in the face of expectations of solid U.S.

growth and the anticipated start of monetary tight-

ening in the United States later this year. Both the

euro and the yen have depreciated about 20 percent

against the dollar since mid-2014. Notwithstanding

the sharp nominal appreciation of the dollar since

mid-2014, the real value of the dollar, measured

against a broad basket of currencies, is currently

somewhat below its historical average since 1973 and

well below the peak it reached in early 1985.

Foreign equity indexes were mixed over the period.

Japanese equities outperformed other AFE indexes,

helped by the BOJ’s asset purchase expansion. Euro-

area equities are up modestly from their mid-2014

levels, boosted recently by monetary easing. How-

ever, euro-area bank shares substantially underper-

for med broader indexes, partly reflecting low profit-

ability, weak operating environments, and lingering

vulnerabilities to economic and financial shocks.

EME equities indexes were mixed, with most emerg-

ing Asian indexes rising and some of the major Latin

American indexes moving down.

Economic growth in the advanced foreign

economies, while still generally weak, firmed

toward the end of the year

Economic growth in the AFEs, which was weak in

the first half of 2014, firmed toward the end of the

second half of the year, supported in part by lower

oil prices and more accommodative monetary poli-

cies. The euro-area economy barely grew in the third

quarter and unemployment remained near record

highs, but the pace of economic activity moved up in

the fourth quarter. Notwithstanding more supportive

monetary policy and the recent pickup in euro-area

growth, negotiations over additional financial assis-

tance for Greece have the potential to trigger adverse

market reactions and resurrect financial stresses that

might impair growth in the broader euro-area

economy. Japanese real GDP contracted again in the

third quarter, following a tax hike–induced plunge in

the second quarter, but it rebounded toward the end

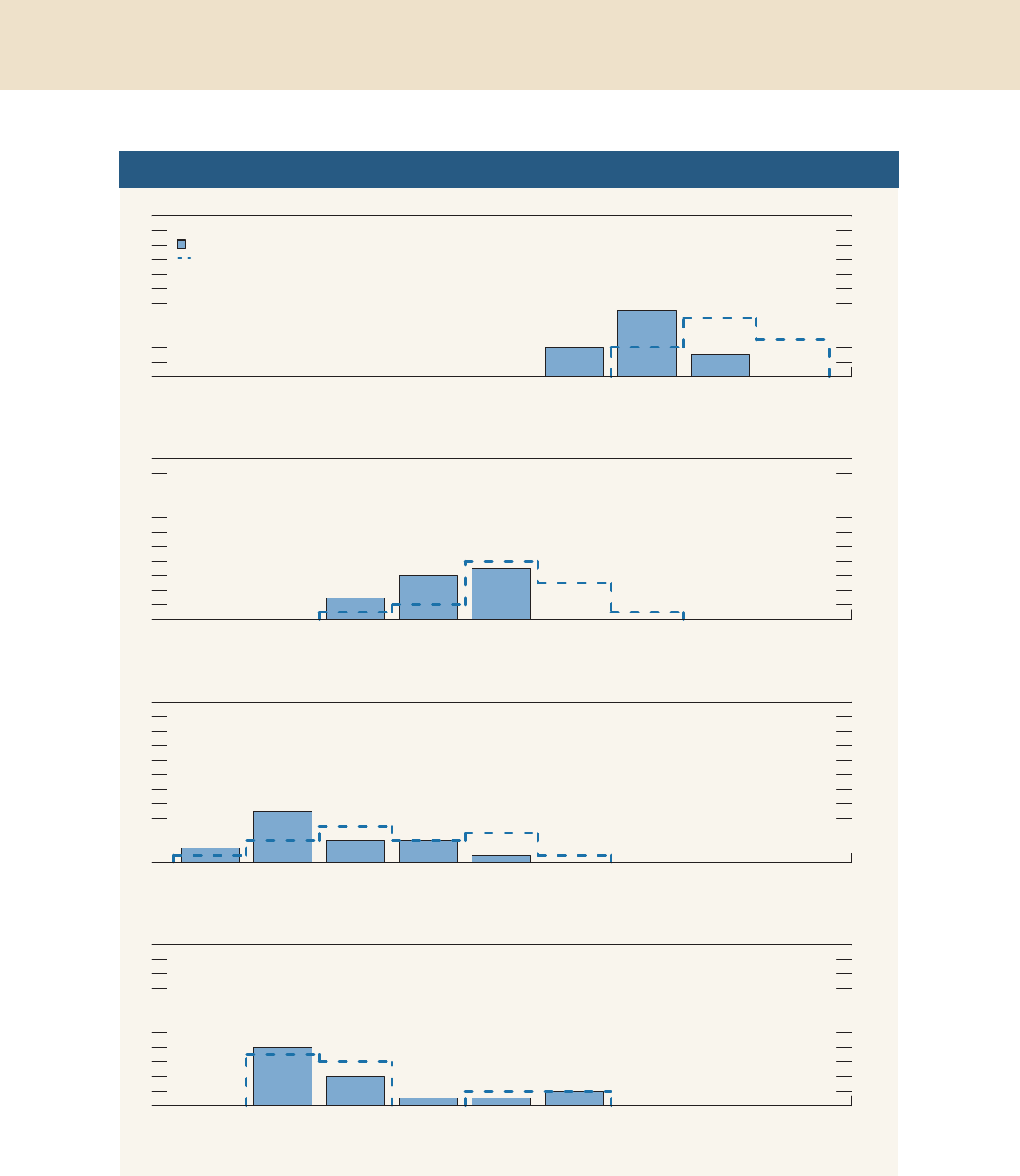

Figure 16. 10-year nominal benchmark yields in advanced

foreign economies

Japan

Germany

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

Percent

201520142013

Daily

United Kingdom

Source: Bloomberg.

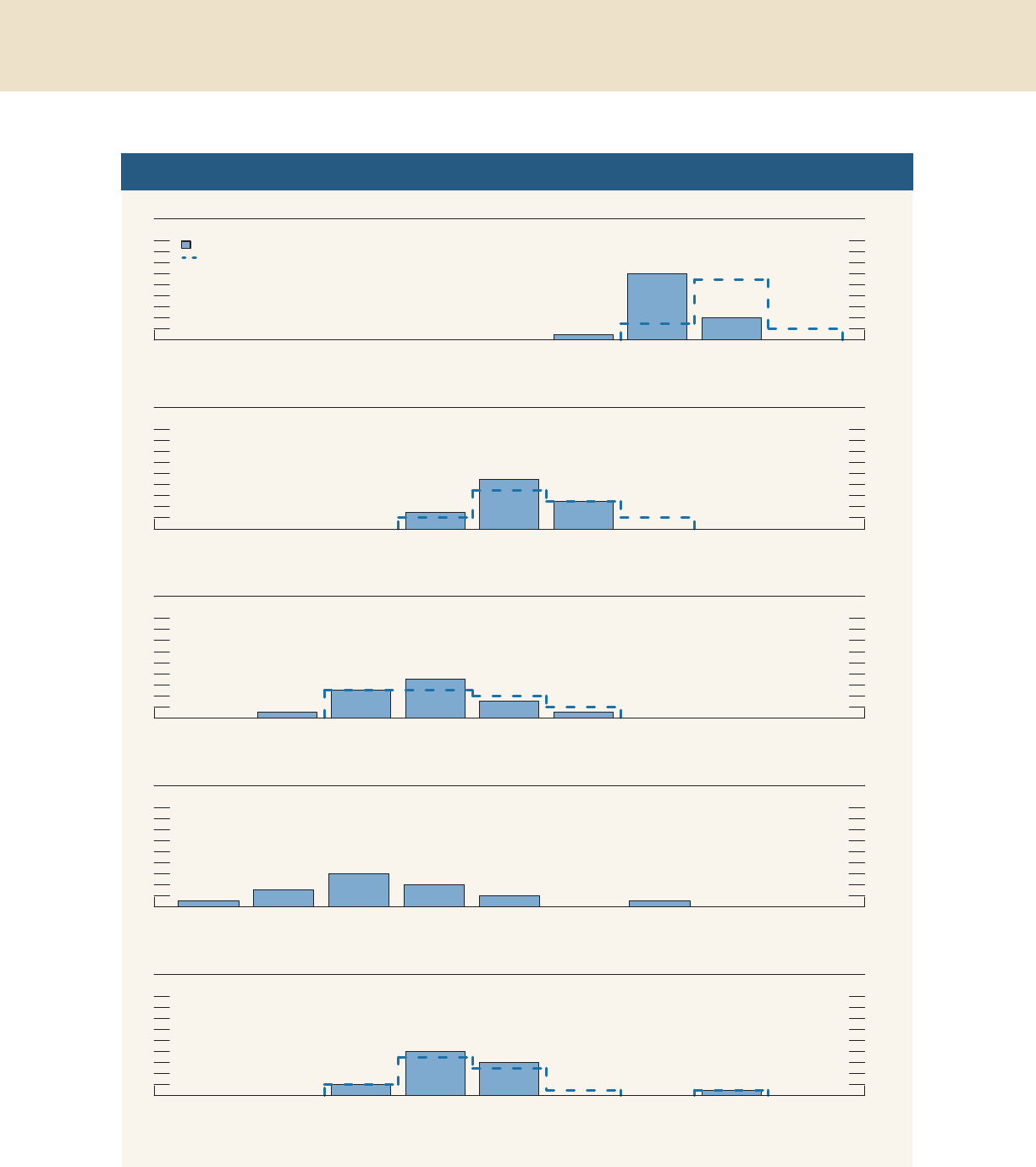

Figure 17. U.S. dollar exchange rate against broad index

and selected major currencies

Yen

Broad

90

95

100

105

110

115

120

125

130

135

140

145

150

155

160

January 4, 2012 = 100

2015201420132012

Daily

Euro

Note: The data are in foreign currency units per dollar.

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release H.10, “Foreign Exchange

Rates.”

Monetary Policy and Economic Developments 17

of the year as exports and household spending

increased. In contrast, economic activity in the

United Kingdom and Canada was robust in the third

quarter but moderated in the fourth quarter.

The fall in oil prices and other commodity prices

pushed down headline inflation across the major

AFEs. Most notably, 12-month euro-area inflation

continued to trend down, falling to negative 0.6 per-

cent in January. Declines in inflation and in market-

based measures of inflation expectations since mid-

2014 prompted the ECB to increase its monetary

stimulus. Similar considerations led the BOJ to step

up its pace of asset purchases in October. The Bank

of Canada lowered its target for the overnight rate in

January in light of the depressing effect of lower oil

prices on Canadian inflation and economic activity,

as oil exports are nearly 20 percent of total goods

exports. Several other foreign central banks lowered

their policy rates, either reaching or pushing further

into negative territory, including in Denmark, Swe-

den, and Switzerland—the last of which did so in the

context of removing its floor on the euro-Swiss franc

exchange rate.

Growth in the emerging market economies

improved but remained subdued

Following weak growth earlier last year, overall eco-

nomic activity in the EMEs improved a bit in the sec-

ond half of 2014, but performance varied across

economies. Growth in Asia was generally solid, sup-

ported by external demand, particularly from the

United States, and improved terms of trade due to

the sharp decline in commodity prices. In contrast,

the decline in commodity prices, along with macro-

economic policy challenges, weighed on economic

activity in several South American countries.

In China, exports expanded rapidly in the second

half of last year, but f ixed investment softened, as

real estate investment slowed amid a weakening prop-

erty market. Responding to increased concerns over

the strength of growth, the authorities announced

additional targeted stimulus measures in an effort to